Estimated read time: 5-6 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

SALT LAKE CITY -- One of the most difficult and troubling aspects of the immigration battle is what to do about millions of children. Born on both sides of the border, they're caught in the crossfire of the debate.

The children of undocumented immigrants are caught between two cultures -- often with stronger ties to the United States than Mexico. They face what new immigrants have lived with throughout history: outright discrimination, as well as serious questions about their right to pursue the American dream.

Two stories of immigration

John Florez didn't grow up on the wrong side of the tracks.

I'm more American than Mexican, because I was raised here. ... If I could have those papers in my hand, I know I would give 100 percent.

–undocumented immigrant

"No. We were in the middle of the tracks," Florez says.

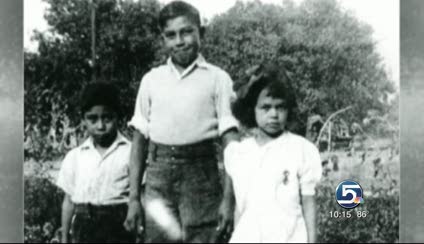

Literally in between the tracks at 700 South and 600 West, he and two older siblings lived in an old railcar. His Mexican Dad was a laborer for the railroad.

Florez never knew his nine even older siblings.

"They all died of different diseases. You know, they didn't have health care at that time," Florez says.

Florez was born in Salt Lake City, a U.S. citizen. He doesn't know if his parents were here legally at that time, although they did re-enter the country again later and became legal residents.

"I saw the University of Utah up there. That was a far-off place. The best I thought I could be would be the switchman," Florez says.

Three-quarters of a century later, two young women have grown up in the shadows. They are sisters who moved to the United States as children of migrant workers.

"Since we were little, we knew that we were here illegal," the older sister says.

"I grew up here. I had American babysitters," the younger sister says.

"I'm more American than Mexican, because I was raised here," the older sister added.

Two different futures

In Florez's childhood, there was hostility even for those here legally.

"Yes, gross discrimination. I was called a savage," Florez said. "I was called a ‘dirty Mexican.'"

But his family drilled some advice into him.

#florez_hatch

"They said, ‘No trabajes como burro' -- don't work like a donkey. Get an education," Florez said.

He took the advice, all the way to that faraway place on the east side: the University of Utah. There, he made honor roll, obtained a master's degree, and earned a professorship.

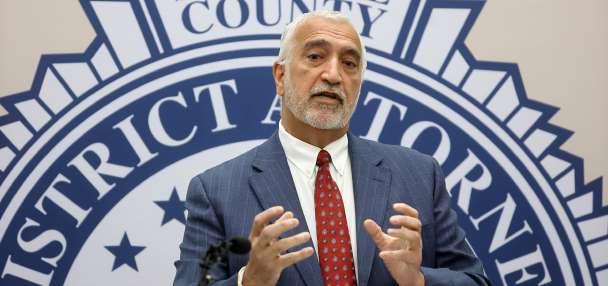

Florez was appointed to White House positions four times. He was deputy assistant secretary of labor and a top aide to Sen. Orrin Hatch.

Those experiences in Washington gave him insight into our complicated attitudes about immigrants.

"The history of this country is one of immigrants coming to build the workforce needs of this country," he said.

The undocumented sisters started with ambitions similar to Florez.

"I was an ‘A' student. I was student of the month, teacher's aide," the older sister said. "I was getting scholarships, but I turned them down because of my status."

She said she feared someone would ask for legal papers or a Social Security number, so she didn't take the scholarships. Now she works three jobs, hoping someday to get into college in spite of her illegal status.

"If I could have those papers in my hand, I know I would give 100 percent," she said.

Her younger sister got into college by keeping her legal status secret. She left blank the space for her Social Security number.

"I would hope that people would understand and be open-minded and open-hearted," the younger sister said. "We're trying to make a living here as well. We're trying to progress as well as you are."

Dealing with legal children of illegal immigrants

Florez thinks his story would not have been much different if he had been undocumented. Legal status didn't used to make much difference, he said, but in the post-9/11 world it does.

I would hope that people would understand and be open-minded and open-hearted. We're trying to make a living here as well. We're trying to progress as well as you are.

–undocumented immigrant

"It's tough economic times. When things are tough, we look for scapegoats," Florez said.

Clearly, many think legal status should matter. At a recent town hall meeting, a questioner expressed worry about legalizing people already here.

The man asked Sen. Hatch, "Given your support of the ‘Dream Act,' how can you convince me that you're not going to support legislation that incentivizes illegals to come to Utah and to this country?"

Hatch told the crowd he does not support amnesty, but expressed compassion for the children.

"A lot of these kids are brought in as infants. They don't even know that they're not citizens until they graduate from high school," Hatch said. "If they've lived good lives and they've done good things, why do we penalize them and not at least let them go to school?"

In a written statement later, Hatch said he does not favor a special path to citizenship for such children -- a view shared by Cherilyn Eagar, of the Coalition on Illegal Immigration.

"Send them back to their home of origin and allow them to come back through and do it legally," Eager said. "It's going to benefit everybody."

We have to follow the rule of law; and if we keep sending that message that we are not going to follow the rule of law, we will keep compounding this problem.

–Cherilyn Eager

But Florez thinks Utah shouldn't turn its back on promising kids who could turn out to be a strength, if America would allow it.

"We have the potential of Bill Gates, Maurice Warshaw, Bill Marriott, sitting in those classrooms right now," Florez said.

"We have to follow the rule of law," Eager countered, "and if we keep sending that message that we are not going to follow the rule of law, we will keep compounding this problem."

"If I could, I would change it," the younger of the two undocumented sisters said. "If I was a bit older when this happened, or if I knew the situation we were going to get into, I would have begged my parents to have done it the right way."

There's one thing on which those two sisters might agree with Eagar: living in the shadows forces them into a secretive subculture and makes it difficult to fully assimilate. But it's one thing to agree on a problem, quite another thing trying to agree on a solution.

E-mail: jhollenhorst@ksl.com