Estimated read time: 2-3 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

SALT LAKE CITY -- Could adjusting the rhythms of the heart reduce the risk of Alzheimer's disease and dementia?

At a major medical conference Wednesday, researchers from Salt Lake's Intermountain Medical Center presented some remarkable new findings.

Last year, researchers from IMC found a groundbreaking link between a common heart disorder called atrial fibrillation and the development of Alzheimer's disease and dementia.

Now, in this new study, they've discovered something that just might reverse the risk.

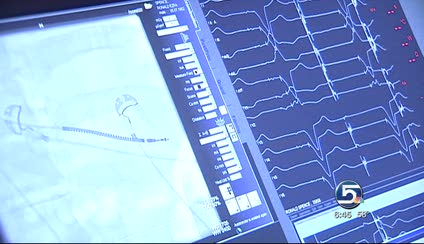

When the heart's electrical system misfires, causing an irregular beat, physicians perform what is called a catheter ablation. During the procedure, which occurs in an outpatient catheter lab, doctors snake a catheter up into the heart and simply disrupt the bad signals to the heart. It takes only about an hour to cauterize those areas of electrical disturbance.

In evaluating almost 38,000 patients, doctors John Day and Jared Bunch discovered what could be a dramatic secondary payoff.

According to Bunch, not only did the risk of stroke drop, "dementia rates, including Alzheimer's dementia, were lower than people who didn't have atrial fibrillation -- and death as well."

The risk of Alzheimer's dropped, as did death rates and the risk of dementia.

"They were all highly statistically significant," Bunch says.

With this second study now, pieces of the puzzle seem to be falling into place. Bunch says, "You start putting pieces together of the association, and it makes you think strongly about profusion of the brain and function of the heart."

If patients could become more aggressive treating high blood pressure, obesity, sleep apnea or other triggers tied to heart function 20 years earlier, could they prevent the progression of Alzheimer's disease or dementia? Perhaps. That's what researchers hope to find out in more studies.

IMC's findings were presented Wednesday in Denver at a meeting of the Heart Rhythm Society.

E-mail: eyeates@ksl.com