Estimated read time: 6-7 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

Editor's note: This article is a part of a series reviewing Utah and U.S. history for KSL.com's Historic section.

BRYCE CANYON — Thursday marks 100 years since U.S. President Warren G. Harding designated Bryce Canyon a national monument, putting it on track to become Utah's second national park almost five years later.

The canyon contains "unusual scenic beauty, scientific interest and importance and it appears that the public interests will be promoted by reserving these areas with as much land as may be necessary for the proper protection thereof as a national monument," Harding wrote in his proclamation.

But the steps to get to that point began many years before Harding's proclamation and there were a few steps left before turning the canyon into the park that millions of people visit every year.

The park's origin

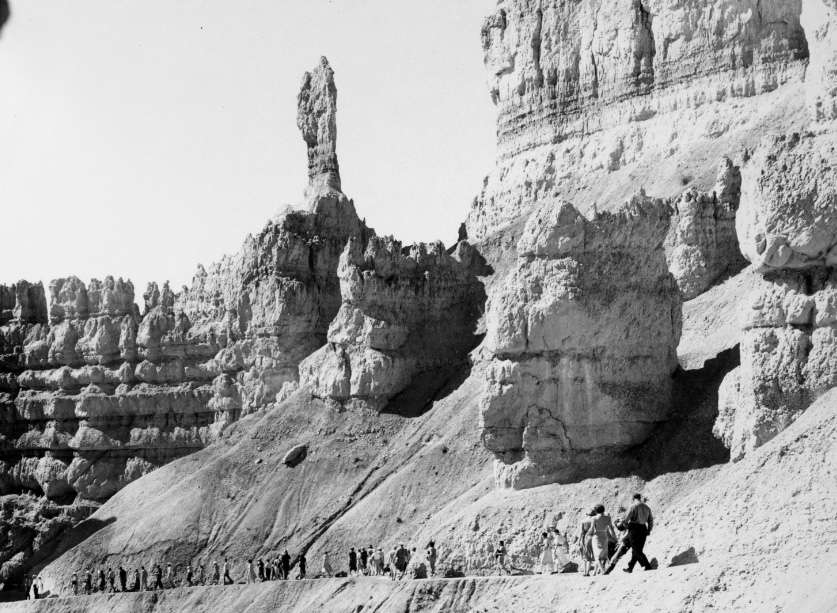

Bryce Canyon's unusual scenic beauty took millions of years to craft. Its "distinctive" red rock hoodoos, spires and towers were formed first through the vast water that used to exist in the region, before these rocks were reshaped through the shifting of the earth, weathering and erosion over a long period of time into the splendor seen today, the U.S. Geological Survey noted.

While Native Americans were known to live in the surrounding areas, about 12,000 years ago, the National Park Service points out that the earliest known human interaction with what is now known as Bryce Canyon dates back to the Fremont culture at about 200 A.D., with the Paiute Tribe occupying it for the first time around 1200 A.D.

Multiple explorers either passed through the area or likely did in the 1700s and early 1800s, before Ebenezer Bryce and his family settled in 1875, joining a few families that moved to the area the year before. Park historians wrote that Bryce helped build a seven-mile irrigation ditch and built a road in the area, leading to people calling it "Bryce's Canyon" — a name that would eventually stick.

But the story of how it ended up as a national park essentially began in the early 20th century. Historians point to U.S. Forest Service Supervisor J.W. Humphrey as the person "most responsible" for making the canyon a national park. He was transferred to a station in nearby Panguitch in 1915 and wrote that visiting what is now known as Sunset Point set off his desire to protect the area.

"It was sundown before I could be dragged from the canyon view," he wrote, adding that he came back the next morning to view it again and to "plan in my mind how this attraction could be made accessible to the public."

He started by taking photos and short motion pictures that he sent to the U.S. Forest Service's main headquarters in Washington. He was awarded a $50 appropriation in 1916 — about $1,500 in today's dollars — to improve a road in the area so the canyon rim could be more accessible by automobile.

Within a few years, it was a popular attraction within the state. Park historians point out that a local couple, Ruby and Minnie Syrett, started to set up tents and supply meals for tourists in 1919. They constructed a 30-by-71-foot lodge called "Tourist's Rest" a year later, along with a handful of cabins and an outside dance floor.

Union Pacific acquired Tourist's Rest in 1923 and helped build a lodge near Sunset Point, according to historians. They also operated the Utah Parks Company, which bused visitors in from a railroad stop in Cedar City, per UtahRails.net. The Syretts, meanwhile, moved to a spot outside of the park and opened Ruby's Inn, which is still in operation today.

Utah Sen. Reed Smoot also started trying to get Bryce Canyon designated as a national park around the same time tourists started flocking to the area. He first introduced a bill seeking to establish what was called "Utah National Park" in November 1919, about 10 days before Zion National Park became the state's first national park.

It seems that Bryce Canyon was destined for some type of protection by 1923, one way or another. The Times Independent, a Utah newspaper at the time, reported in January of 1923 that Utah Gov. Charles Mabey outlined several laws he wanted passed during that year's legislative session. One of those would have initiated "a system of state parks, with especial reference to Bryce Canyon." This obviously didn't materialize, as Utah's state park system wasn't established until 1957.

A few months later, Harding designated Bryce Canyon a national monument in what would ultimately become the last proclamation he ever issued before his death less than two months later, according to documents kept by the University of California, Santa Barbara's "The American Presidency Project."

Utah is blessed with more than her share of natural wonders. Of all these, none is more awe-inspiring than Bryce Canyon.

– Mt. Pleasant Pyramid, 1923

There aren't many reports of Harding's proclamation among digitized newspapers, possibly because it didn't change much. The National Park Service points out that the U.S. Forest Service maintained control over the land, which it already controlled because it was within a national forest, writing the designation, was, theoretically, "nothing more than an extension of supervision for Powell National Forest."

But it does appear many Utahns were happy about the area being protected. On June 8, 1923, the Mt. Pleasant Pyramid printed a glowing review of the canyon.

"Utah is blessed with more than her share of natural wonders. Of all these, none is more awe-inspiring than Bryce Canyon," the outlet wrote at the time. "It is defiant of description and immune of reflection, conveying an adequate impression. Great artists have gone there only to return with a realization of the weakness of man."

Of course, the story wasn't over from there. Congress eventually passed the bill designating Utah National Park in June 1924. This process wasn't finalized until Feb. 25, 1928, which is also when the name Bryce Canyon was also restored. The Salt Lake Telegram reported at the time that this finalization was "distinctly gratifying to Utahns."

The park was originally about 7,700 acres in 1928 but would grow to its current size of 35,835 acres by 1931, as a result of a pair of proclamations issued by U.S. President Herbert Hoover, according to the park service.

The park today

While Bryce Canyon is Utah's smallest national park, it is consistently the state's second-busiest park. Visitation has grown from a little more than 550,000 in 1979 to more than 2 million visitors in six of the past seven years. Only Zion National Park among Utah's "Mighty 5," brings in more crowds.

Utah Gov. Spencer Cox, who declared Thursday to be Bryce Canyon Day in Utah, wrote that more than 60 million visitors have come to the park since official records were first kept in 1929. Its popularity helped support more than 2,500 jobs and $250 million in economic impact in 2021.

It's a park that continues to captivate visitors, as it did with Humphrey, the Mt. Pleasant Pyramid and countless others over a century ago.

"I have been wanting to go since I was young and it definitely lived up to my expectations," one person wrote in a five-star Google review earlier this year. "This was amazing!"