Estimated read time: 17-18 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

SALT LAKE CITY — Drs. Cara Heuser and Alexandra Eller say the way Utah's abortion trigger ban law is written leaves them in an impossible situation.

Both maternal fetal medicine physicians based in Salt Lake City say they're caught between their professional duty to protect the lives of both pregnant mothers and their babies — and a fear that even if they prescribe or perform what seemingly should be a legal abortion under the exemptions listed in the law, they could still end up getting charged with a second-degree felony.

And they're not alone. Other physicians — and assisting nurses and pharmacists — have been questioning their own possible culpability based on the language in SB174. It contains language that even prosecutors say they could have a difficult time interpreting.

"It's putting people in a really scary position," Eller said.

The result? A chilling effect, which they worry will frighten doctors from giving pregnant mothers — or even women recovering from miscarriages or other complications — the treatment or help they need, even if it's for a situation that would seemingly allow a legal exemption, whether it be to protect the life of the mother or if the fetus has a "uniformly diagnosable" defect or "severe brain abnormality."

"It can't help but to impact one's judgement when you know the potential consequences of fearing you might break this law based on someone else's interpretation. You're talking about your career, your livelihood, your ability to support your family," Eller said. "So when that clouds a physician's judgement, that's a problem."

But first and foremost, Eller and Heuser said their "No. 1 concern" is for pregnant mothers. If physicians are hesitant or reluctant to give them the help they need — especially in emergency situations — they're the ones who will suffer.

"Women are at risk," she said. "We want people to be able to do the right thing, but it's very hard to know how to (interpret) this law."

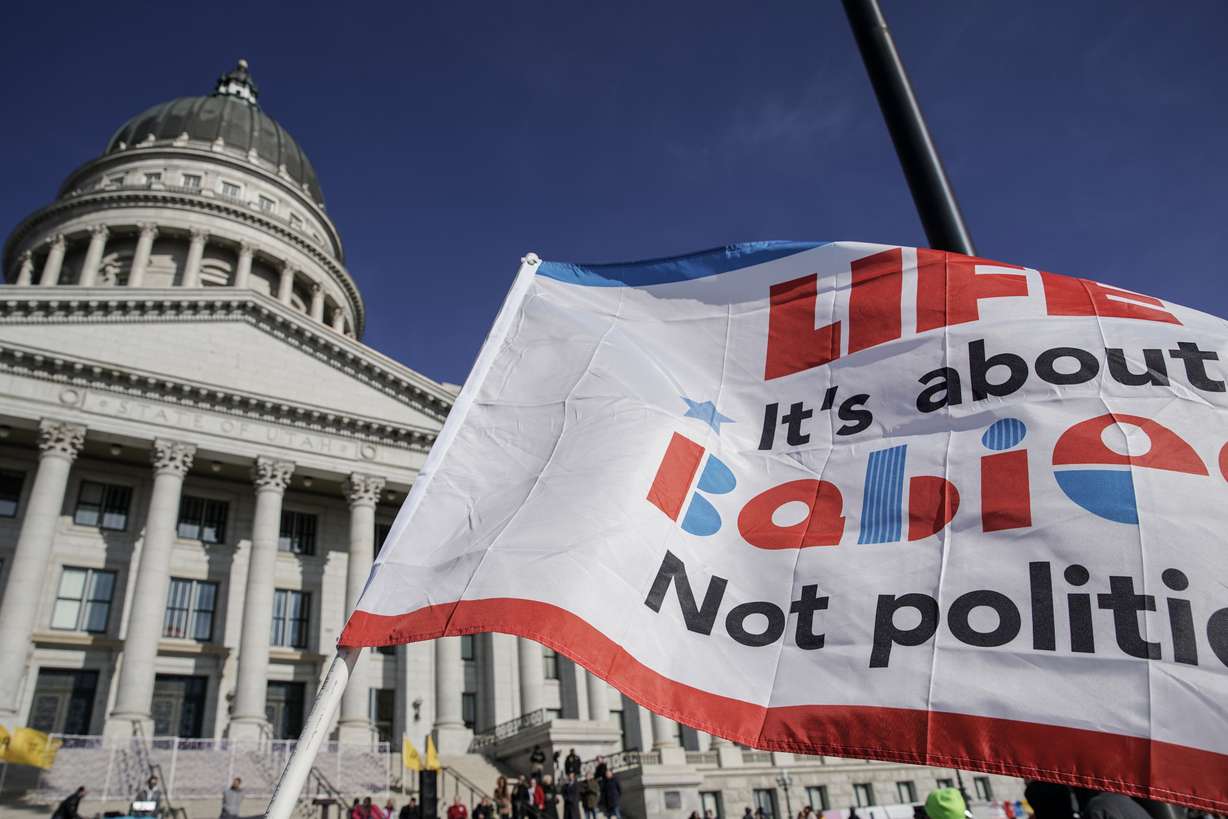

Utah lawmakers passed SB174 in 2020 seeking to position Utah to protect the life of unborn children if or when the U.S. Supreme Court overturned the landmark Roe v. Wade ruling. That decision came last month, and Utah's trigger abortion ban took effect briefly before it was placed on a temporary hold as Planned Parenthood's lawsuit with Utah plays out.

We're putting our prosecutors and even our law enforcement officials and, really, our health care officials in a compromising position.

–Rep. Angela Romero, D-Salt Lake City

The bill's sponsor, Sen. Dan McCay, R-Riverton, did not respond to a request for comment for this story, but Senate President Stuart Adams, R-Layton, told the Deseret News in an interview that needs for tweaks or clarification are not uncommon after legislation takes effect — but he wants to see the law actually implemented. If issues arise, then he said lawmakers can decide whether to make changes to the law.

"I think it's really important that we find out what the actual problems are," Adams said. "If there are problems ... then I think legislators will pick it up and try to fix those functional problems."

Eller and Heuser said their jobs as maternal fetal specialists is to "promote the safest and healthiest pregnancy outcomes for moms and their babies" — but they fear SB174's language, even though it seeks to leave exemptions for mothers, is problematic in practice.

"We work every day to help babies get as far into pregnancy as they safely can, for interventions in utero to help them survive. Our goal is to protect the mother and the baby. That's our job. ... And each case is very unique."

Dr. Lori Gawron, a general OB-GYN and a subspecialist in complex family planning based in Salt Lake City, also shared similar concerns. She agrees SB174 isn't "written in a way that makes sense under our medical guidelines and practice."

"Since the result is a felony, it's hard to interpret and ... it instills fear in health care providers, and they will absolutely delay care for patients because of uncertainty and ambiguity in the way the language is right now," Gawron said.

But even though the law is currently on hold (while Utah's other law banning abortion after 18 weeks of pregnancy is in effect), Eller said she and her maternal fetal medicine partners have been getting phone calls from others feeling unsure and at risk over how to treat their patients.

"Already, even (with the stay), we and our partners have received multiple phone calls from doctors in exactly those situations where someone is experiencing an obstetric, urgent situation, and they feel uncertain of what to do when a few months ago they would have known exactly what to do" in situations when a physician has decided the right thing to do is to end a pregnancy for the mother's safety, Eller said.

"Instead, they're calling, saying, 'Help me. I'm now worried that I might be breaking the law,' or 'Would I be breaking the law?' And so it's created a level of ambiguity that we fear will promote significant maternal risk."

Heuser said she's had conversations with not only her partners, but also her spouse about the risks of continuing caring for her patients under the murky constraints of SB174.

"Everyone is very scared of that," Heuser said. "It's a big deal."

Gawron also wants to care for her patients, but she, too, is fearful of being charged with a felony — even if she thinks it's the right or legal decision based on her own interpretation of the law.

"I have that concern despite being very informed about the law because of the language and ambiguity and the fact that it's not based on medical evidence or diagnostic criteria," Gawron said, referring to the definitions spelled out in the law.

While "we appreciate" the intention of the exemptions outlined in Utah's trigger law, Heuser said their language is "quite vague, and it's unclear who makes the decision" about whether an abortion would be legal or not.

The problems don't stop there.

Pharmacists say they also aren't clear about what medications — even some that have a variety of other uses — they can legally dispense, and if they're obligated to ask patients, right there at the local grocery store pharmacy, if they intend to use it for an abortion.

And there is an entire separate mountain of concerns around the language for the exemption for rape and incest victims, which requires the rape to be reported to police and physicians to "verify" that report, with no clear standard or explanation of how a provider would be required to do so.

What's in the law and how will it be enforced?

Utah's trigger abortion law, SB174, bans most abortions in Utah, but spells out exemptions for what it describes as "medical emergencies" that could threaten the life of the mother or if she's at "serious risk of substantial and irreversible impairment of a major bodily function."

It also lists exemptions if two maternal fetal medicine doctors "concur, in writing," that the fetus "has a defect that is uniformly diagnosable and uniformly lethal; or has a severe brain abnormality that is uniformly diagnosable."

And it also includes an exemption if the woman is pregnant as a result of rape or incest.

As written, the law doesn't criminalize women seeking abortions. Rather, criminal penalties would fall on physicians who perform an abortion in violation of the law.

Enforcement of the law falls to two state agencies — the Utah Department of Health (now consolidated into the state's Department of Health and Human Services) — and the Utah Department of Commerce's Division of Occupational and Professional Licensing. If health department officials are made aware of any violation of the law, SB174 requires them to report the violation to the Division of Occupational and Professional Licensing. Additionally, health officials "may take appropriate corrective action against an abortion clinic, including revoking the abortion clinic's license."

Beyond that, Division of Occupational and Professional Licensing officials could forward complaints to law enforcement. Plus, anyone with a complaint could go directly to their local law enforcement agencies with a report of violations. Therefore, enforcement of the law appears to be mainly complaint driven.

Things also get murky when it comes to scenarios including mail-order abortion pills or telehealth visits — as well as scenarios in which a woman might travel out of state, get an abortion pill from a doctor not licensed in the state of Utah, and then bring it back home to take the pill.

The law defines the word "abortion" as the "intentional termination or attempted termination of human pregnancy after implantation of a fertilized ovum through a medical procedure carried out by a physician or through a substance used under the direction of a physician."

A "physician," as defined under SB174, is "a medical doctor licensed to practice medicine and surgery in the state; an osteopathic physician licensed to practice osteopathic medicine in the state; or a physician employed by the federal government" with similar qualifications.

Because the law criminalizes those who "perform an abortion," not the woman seeking the abortion, the language of the law appears to contain a loophole for women obtaining abortion pills from doctors licensed out of the state of Utah, including by mail, but still taking them at home in Utah.

However, while SB174 states a physician may only perform a legal abortion, it also states "a person who performs an abortion" in violation of the law is guilty of a second-degree felony. Could "person" also include an assisting nurse? A pharmacist? These are the questions that physicians and pharmacists are grappling with without clear answers.

"What counts?" Gawron questioned. "I think that's really confusing. ... It really is broad reaching."

Hurdles facing rape victims, prosecutors

Dave Ferguson, executive director of the Utah Association of Criminal Defense, shared similar concerns as physicians — that because of ambiguities in the language of the law, prosecutors could have a different interpretation of what qualifies as a legal exemption.

For example, the words "serious risk," "substantial" and "irreversible impairment of a major bodily function" aren't medical definitions, and law enforcement officials could interpret them differently than a physician.

"All these adjectives is really where it gets concerning," Ferguson said. "Health care providers are left to interpret the various ranges of risks ... and have to find a way to plug these into the law with the risk that a police officer who is not a physician and a prosecutor who is not a physician might not understand the medical world very well."

Heuser noted medicine is "not black and white" and these nonmedical, absolute adjectives make her nervous. "I don't have a crystal ball. I can counsel patients in terms of probabilities and risks and likelihood, but it's very hard for me to ever be 100% certain about something being permanent and irreversible."

County attorneys, in particular, raised concerns about how to interpret the reporting requirement for the rape exception. They said they're not sure what standard to use to check whether a physician properly verified if a rape was reported to police.

"The Legislature did not specifically define the term 'verify.' They didn't lay out the process," Davis County District Attorney Troy Rawlings told the Deseret News, questioning if it means a physician would need to call the police department, obtain a copy of the police report or make some other effort to confirm.

"These are all the kinds of questions that we'll grapple with in real time as cases come into our office," Rawlings said, though he added prosecutors would use their best judgement to determine if verification was sufficient and a viable legal defense.

There are also concerns about how requiring rapes to be reported to law enforcement in order for a woman to be eligible for the exemption could impact rape victims, who might not want to report the rape for a wide variety of reasons, including their own safety.

"Sexual assault is underreported as it is, and a lot of individuals will never go to law enforcement," said Rep. Angela Romero, D-Salt Lake City. "So I really feel like we're putting those individuals in a compromising position."

We and our partners have received multiple phone calls from doctors in exactly those situations where someone is experiencing an obstetric, urgent situation, and they feel uncertain of what to do when a few months ago they would have known exactly what to do.

–Dr. Alexandra Eller

Romero, who has passed several bills related to sexual assault, has filed a bill to remove the criminal penalty from Utah's trigger law, which she intends to run during the 2023 general session. She agrees there are problems with the law that need to be at least clarified, if SB174 is going to be the law of the land in Utah.

"We're putting our prosecutors and even our law enforcement officials and, really, our health care officials in a compromising position," Romero said. "I'm just horrified and I have major concerns."

Salt Lake County District Attorney Sim Gill also agrees there are areas of SB174 that could be tricky to interpret. That's why "I'm genuinely curious about how these investigations are going to go about," he said.

The rape exemption and reporting requirement is just one example.

"What is going to constitute appropriate reporting? What is that verification going to look like?" Gill asked, adding, "I cannot be blind to the fact that it is going to create unnecessary burdens for victims who are undergoing a really traumatic time in their life, to be subjected to this."

Gill also said he's "genuinely concerned about revictimizations" of rape victims, and the "collateral consequences" of requiring them to go to law enforcement. He worried that the reporting requirement could actually arm the defense of a rapist, who could then argue the woman only reported the rape in order to seek an abortion.

"There will be collateral attacks made on victims, and that does not make me feel good about that process," Gill said. "So while our Legislature has created a law, I don't know we have fully thought through the process of what that collateral consequence might be for victims."

Asked about how prosecutors will grapple with ambiguities within the law, Gill said prosecutors will not "abdicate our responsibility to be very meticulous and to be very deliberate, just like in any case that's presented to us. ... We need to be very cautious and deliberate" based on actual evidence.

"And I'm genuinely curious what those investigations are going to look like — what is going to constitute good evidence," he said.

In response to questions about the rape reporting requirement, Adams noted the reporting requirement isn't new. A similar requirement was first included in a 1991 law limiting abortions and again in a law passed in 2009. Adams said lawmakers haven't been aware of any issues related to that requirement.

"It's functioned very well," he said.

Could the law also have a chilling effect on pharmacies?

Utah's trigger law is mum on pharmacies and whether they would be held legally responsible for an illegal abortion — and that lack of clarity is making some pharmacists nervous, possibly to the point of avoiding dispensing certain medications, including some used for treatments other than abortion.

That's according to Dave Davis, president and CEO of the Utah Retail Merchants Association, which also represents pharmacies of all sizes — from big store pharmacies like CVS, Walgreens and Walmart, to small local pharmacies.

One medication in particular — misoprostol — is commonly used as part of a medication abortion.

"Here's our challenge from a pharmacy point of view," Davis said. "If you have a woman that walks into a pharmacy ... and they're coming in for a misoprostol prescription, we're confused about what's our responsibility at this point."

For a medication abortion, it's common for a physician to prescribe mifeprostone, which "blocks your body's own progesterone, stopping the pregnancy from growing," according to Planned Parenthood's website. Then, the second medication, misoprostol "causes cramping and bleeding to empty your uterus."

"There are lots of uses for misoprostol," Davis said, noting it can be used to help women recover from miscarriages, as well as treatment for stomach ulcers. "And a pharmacist, because of the way the law is drafted when it talks about criminal liability, it says 'a person' — 'a person' who participates in this process is potentially liable."

"And so we're uncertain," Davis added. "What's our responsibility here? Do we have a responsibility to sort of inquire to the patient, 'What is this being used for?' And it feels just totally inappropriate for us in a community pharmacy setting to start sort of giving a woman the third degree about, you know, 'What are you using this drug for and is it being used for an abortion, and if it is do you meet one of the statutory exemptions?'"

A community pharmacy setting "just doesn't feel like that's the spot that should happen. It feels like those are conversations that should be had between the woman and her physician," Davis said.

Pharmacies and pharmacists want to be confident that that's the case — that if it's a prescription legally issued by a physician "we ought to be able to just dispense that drug," he said, but that's not clear in the law's language.

Davis noted some pharmacies he represents are being sued right now by the Utah Attorney General's Office for their alleged role in the opioid epidemic "because the attorney general feels like we didn't ask enough questions about opiates. And so we are legitimately concerned about how we handle these," he said.

"This is what my fear is, is that pharmacies out there will look at it, make an assessment of the potential liability, and just say, 'We're not dispensing misoprostol anymore,'" Davis said.

It's the same chilling effect physicians are facing.

"Then we're going to have women out there that have a legitimate need for this drug — a nonabortive need for this drug — and they're going to struggle to get access to it," Davis said. "Because I know pharmacies want to be careful, they want to abide by the law. And right now, from our perspective, we feel like the law is unclear at that point."

Misoprostol isn't the only drug, he noted, though it's probably the most common affected by Utah's trigger law.

Davis said pharmacies have already started reaching out to lawmakers to make them aware of the issue with the law's language and are hoping they'll step in to clarify it.

"We really do think there needs to be a clarification on this issue," he said. "We're hopeful. The legislators that I've talked to at this point have been receptive, they understand what the issue is and what the concern is, and we're hopeful that they'll be willing to make some of these clarifications."

'Let the law go into effect'

In response to multiple questions sent to his office regarding these uncertainties with SB174, Adams said "we need to be respectful of those concerns."

"With any legislation we pass, there's always ... at times things that need to be tweaked or need to be looked at," Adams said.

However, he said these concerns are cropping up "before the legislation is really even in effect."

"So, I think I've been very clear with my comments, that I want to actually see it implemented and then find out, not what the concerns are but what the actual challenges are as it's implemented," he said. "It's important to have actual factual problems rather than theoretical problems."

Adams noted it's not those who think the exemptions language isn't clear enough. Some even "want to go further" than Utah's trigger law and "take away some of the exemptions."

He reiterated he's "surely respectful about the concerns that people are worried about, but I think it's probably really important to let the law go into effect and actually see how it's administered."