Estimated read time: 9-10 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

SALT LAKE CITY — Utah is closing in on the final chapters of the yearslong, controversial saga of building a new prison from scratch.

It's been coined one of the largest detention projects in the nation. It was, at one point, the largest and most expensive, but since it's 2017 groundbreaking it's been eclipsed by other larger projects that have been set into motion, including New York City's plans to spend nearly $9 billion to build a new jail system to replace the Rikers Island complex.

Here's what you need to know about the massive Utah project, one that will go down as one of the largest construction endeavors in the state's history.

For a more in-depth look inside the new Utah State Prison, read more from the Deseret News' tour here.

1. How big is it?

It's footprint is 1.3 million square feet, spanning about 170 acres, inside and outside the area's secure perimeter.

The prison site is located about 9 miles west of the Salt Lake City International Airport — so far north of I-80 it's barely visible to drivers despite its size.

To develop that remote, mosquito-riddled area, state and Salt Lake City officials spent over $90 million to build 7 miles of roads and 13 miles of power, sewer and water lines.

The campus is made up of over a dozen buildings, designed based on varying levels of security, from medical and mental health, to general population, to maximum security. There are also buildings for administrative work, classrooms and gymnasiums, chapels, culinary, receiving and orientation where inmates meet with caseworkers, visitation, vocational programs and screening, and warehouses to receive supplies.

Uniquely, the prison will have facilities for both men and women within its footprint, though women's facilities are segregated from the men's by a secure outdoor perimeter.

Outside, about 10 miles of razor wire top the secure perimeter's chain-link fence.

Though originally planned to house 4,000 inmates, the new Utah State Prison was downsized to 3,600 beds. Project managers pushed pause on the project in the middle of construction to redesign the facility to save money amid rising costs.

Though the current prison in Draper has the capability to house about 4,300 inmates, Michael Ambre, assistant director of Utah's Division of Facilities Construction and Management, said it currently houses about 2,500 inmates. So even when the new prison opens, it won't be full, he said.

However, capacity is a concern long term. As Utah's population continues to boom, its incarcerated population inevitably will, too. Ambre said state officials can consider several options for when the facility overflows, including room for expansion on the new Salt Lake site (though that would cost more money). Or the Central Utah Correctional Facility in Gunnison could expand.

2. How much did it cost?

Originally, state leaders budgeted $650 million for the new prison. But that price tag swelled to what's now pegged at about $1 billion.

Jim Russell, director of Utah's Division of Facilities Construction and Management, expects the final construction cost to come in "just a little bit under or a little bit over" $1 billion, depending on final procurement processes.

State officials blame that ballooned price tag on construction cost escalation, pointing first to former President Donald Trump's tariffs on China, and then the COVID-19 pandemic, which escalated costs even further with labor shortages and supply chain issues.

Building of the new prison happened alongside the construction of the new Salt Lake City International Airport, which cost over $4 billion. Having two concurrent major projects compounded demand for materials and fueled rising labor costs.

3. When will it open, and when will the old prison be demolished?

Construction of the new prison is slated to be finished by the end of February, according to Ambre, though he notes construction deadlines can change.

Inmates, however, aren't scheduled to move in until June, leaving several months to allow for testing and refinement of the prison's complex electronic security system. Plus, the Department of Corrections will need to train all of its staff on how to operate the new facilities, a process that's already ongoing.

Once all the inmates are out of the old prison and in the new one, demolition will begin, though details of exactly when still need to be sorted out, Russell said.

Currently, Russell expects the demolition and abatement process to begin July 1 and to last up to a year. But before that timeline can be solidified, Russell said he needs to request funding from the Utah Legislature during the 2022 general session, which begins in January.

He declined to give the Deseret News a rough estimate of how much the demolition will cost, saying he's still weeks away from finalizing that budget proposal.

Before demolition can begin, Russell said officials need to conduct an abatement process, which entails removing all hazardous materials inside the building like asbestos and lead-based paint.

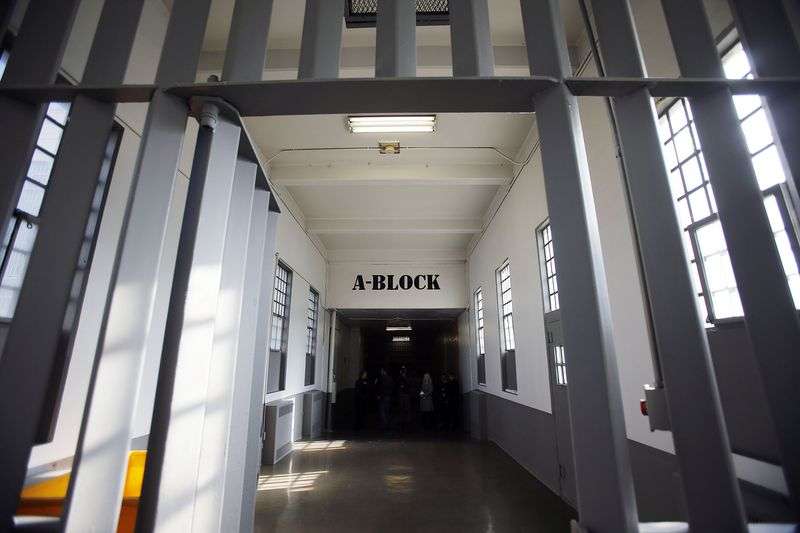

4. What's it like inside?

The new prison's designers based the structure and utility of the new Utah State Prison on one key concept: behavior.

"It has everything to do with behavior in this facility," Ambre said during a tour of the new prison last month. "It has nothing to do with your sentence."

Better behaved inmates will be placed in dorm-style, shared living areas. Poorly behaved inmates will be isolated in single-bed cells, with limited opportunities for interaction with other inmates or guards, Ambre said.

Inside each building is a very sterile environment that looks extremely similar no matter where you go. Concrete walls and floors. Glass windows. Uniform cell doors.

But a color coded system helps differentiate areas and their varying levels of behavior and security.

There's also a geriatric unit for elderly inmates. For those who have histories of good behavior, they'll live in a dorm-style area with access to a large, open area fitted with TVs and tables with games like checkers printed on their surfaces.

Each unit features a day room, or an area where inmates can socialize outside of their cells, which line the walls. In areas with better behaved inmates, a guard will supervise the area using "direct supervision," or a model in which corrections staff are stationed at a desk in the middle of the room.

For units with higher levels of security, corrections staff will monitor inmates from a control room overseeing the units from behind glass panes. There, correction officers can use an intercom system to communicate with inmates and control which cells are open or closed.

The maximum security unit is designed to allow inmates to move from their cells to recreation enclosures (cage-like areas in the recreation yard meant to give inmates time outside) and to the shower without guards needing to shackle and transport them personally to and from their cells. All corrections staff will need to do is open or close cell doors individually, and a sectioned-off area funnels inmates to where they need to go.

Overall, the new prison was designed with a main goal to create a facility that treats its inmates and gives them a shot at a new life, not traps them in a vicious cycle of recidivism. It's designed to have a more "humane" focus — built to rehabilitate inmates, not warehouse them.

The aim, Russell said, is to build a prison that strikes the right balance between being a place of punishment, but also a place with the right environment for inmates to turn their lives around while serving their sentences.

"You don't want to make it so nice that they never want out, but then you also need to provide a place where they can actually change their behavior," Russell said. "I think (Ambre) and his team have done a great job getting the right mix."

5. Why was the Draper prison moved?

In short, development and financial pressures prompted the move.

For 60 years, the prison's current facilities have locked up over 600 acres of prime real estate.

It's located near Point of the Mountain, where I-15 wraps around the Wasatch foothills to connect Salt Lake County, Utah's most populous county, with Utah County, home to the state's tech corridor known as Silicon Slopes. The area has been an epicenter of growth in Utah, which over the last decade has been one of the most rapidly growing states in the nation.

In its place, state leaders envision a massive, "once-in-a-generation" housing and commercial development that's been named The Point.

The grand vision for the former prison site is, so far, a master-planned "complete community," or Utah's first "15-minute city" that would contain everything a person needs to live and thrive within a 15-minute walk from its heart. The plans detail a "vibrant mix" of retail, entertainment, schools, high-quality workplaces, restaurants and recreation.

The move will happen about a decade after Utah leaders began studying whether relocating the prison to free up the prime Draper real estate for development made financial sense. Utah's leaders decided yes, it absolutely made financial sense.

When the prison relocation authority recommended the move in 2014, it estimated the annual economic benefit from developing the prison property would be $1.8 billion, with state and local taxes adding up to $95 million each year.

Today, preliminary figures gleaned by the Point of the Mountain State Land Authority in partnership with the University of Utah's Kem C. Gardner Policy Institute estimate an initial public and private investment of about $200 million — along with billions more in anticipated investment from the private sector — would generate about $6.9 billion in gross domestic product for the state, $4.7 billion in personal income and up to 47,000 jobs.

State leaders decided building a new prison would be more cost-effective than trying to renovate Draper's aging facilities, which lack modern design and technology meant to increase safety and security for both inmates and correctional staff.

State officials estimated it would cost about $239 million in repairs and upgrades over the next 20 years to keep the Draper facility operating, plus an additional $150 million to add program space.