Estimated read time: 4-5 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

SALT LAKE CITY — Steamboat Geyser might take a backseat to Old Faithful in terms of notoriety at Yellowstone National Park, but its eruptions are famously mysterious within the science community.

Steamboat Geyser, which is also the world's largest, has an odd pattern of eruptions. For instance, when it erupted in 2018, it was the first documented eruption in almost four years.

That's not uncommon because geysers are difficult to pinpoint, Michael Poland, the U.S. Geological Survey's scientist-in-charge of the Yellowstone Volcano Observatory, said at the time. Steamboat Geyser just happens to have a different aura that intrigued the science community.

"Most geysers erupt infrequently, unlike Old Faithful, so Steamboat is not enigmatic in that regard. But Steamboat has a mystique about it because it is the tallest active geyser in the world. It gets attention because of this, and rightly so," he said.

Geysers erupt when "superheated" water enters a geyser's plumbing system, which causes the geyser to act like a pressure cooker, the National Park Service explains on its website.

"Within a geyser's plumbing system, much of the water can reach temperatures greater than 400°F and still remain in a liquid state due to the great pressure exerted by overlying surface water and rock," the agency wrote.

The chain of eruptions that began at Steamboat Geyser in 2018 was also the third period of sustained activity ever, and the first since the 1980s. The period of eruptions that began three years ago puzzled scientists, who weren't exactly sure what caused the geyser to suddenly be active again.

But it was perfect timing for new research into how the geyser functioned. So in the summers of 2018 and 2019, a team from the University of Utah's Department of Geology and Geophysics joined a team of National Park Service researchers gathered at the geyser to collect data.

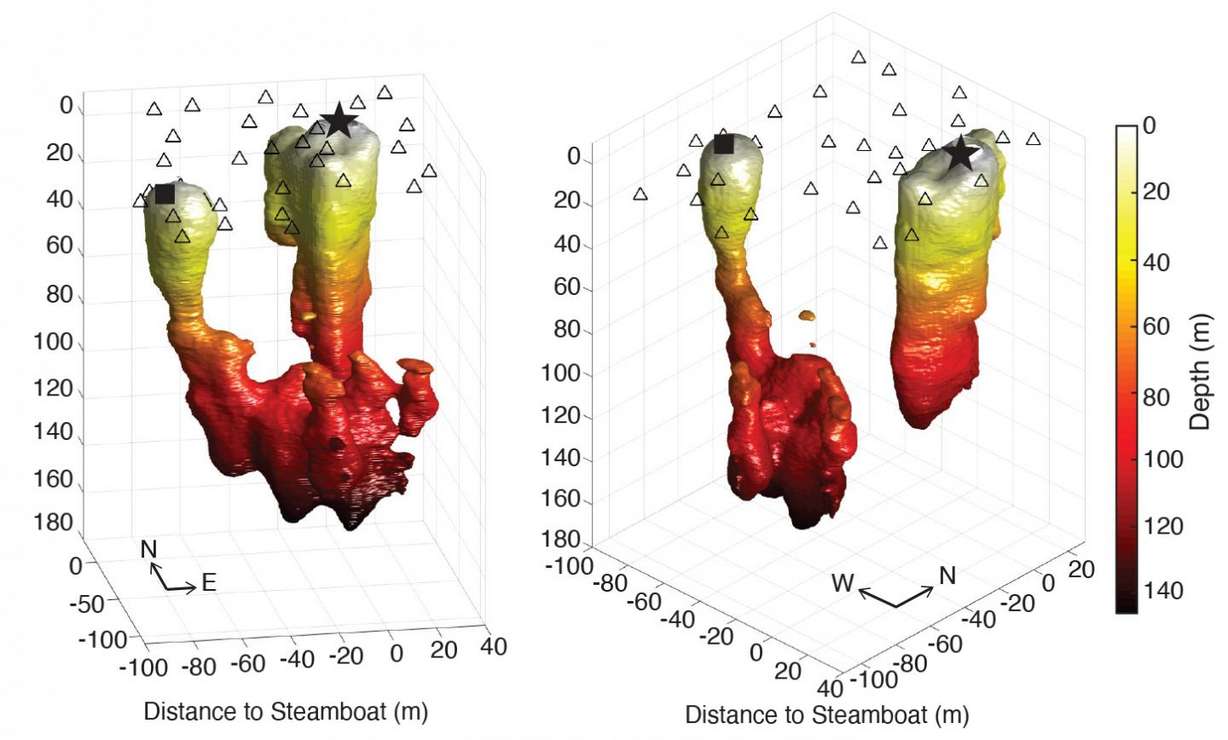

The group placed 50 portable seismometers around the massive geyser. They were able to record seven major eruptions in 2019, and the data gathered allowed the researchers to build an image of the geyser's plumbing.

The University of Utah and the National Park Service teams' findings were published in Advancing Earth and Space Science earlier this month.

What they found is that the geyser extends down at least 450 feet, which is much deeper than Old Faithful's roughly 260-foot depth. The team also found no connection to Steamboat Geyser and the nearby Cistern Spring, which is a pool that was believed to be connected to the geyser in some fashion because it drains about the same time the geyser erupts.

Sen-Mei Wu, one of the researchers on the project, said the discovery allowed the team to rule out the assumption that the two natural features shared some sort of pipe to each other — at least in the upper 450 feet of the geyser.

The research team didn't rule out that the two might be connected much farther underground. For instance, they said it's possible that they're connected through small fractures in underground rock that the seismometers didn't pick up.

"Understanding the exact relationship between Steamboat and Cistern will help us to model how Cistern might affect Steamboat eruption cycles," Wu said in a news release Monday.

For that reason, the findings couldn't pinpoint an exact explanation for the geyser's bizarre eruption pattern. Researchers say it's possible the code will be cracked sometime in the future, once scientists have a better grip on piecing together how hydrothermal tremors work and with a more long-term monitoring system.

It means the study creates a baseline understanding of how Steamboat Geyser works during a non-frequent eruption cycle.

"When it becomes less active in the future, we can re-deploy our seismic sensors and get a baseline of what non-active periods look like," added Fan-Chi Lin, an associate professor in the University of Utah's Department of Geology and Geophysics. "We then can continuously monitor data coming from real-time seismic stations by Steamboat and assess whether it looks like one or the other, and get a more real-time analysis of when it looks like it is switching to a more active phase."

Until then, the Steamboat Geyser continues to be a mysterious natural wonder.