Estimated read time: 5-6 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

SALT LAKE CITY — The looming threat is hard to ignore at the University of Utah hospital intensive care unit.

The nurses have sensed it for months as they've treated COVID-19 patients restricted to ventilators and seen beds fill up. The images of what happened in New York City in the spring flood the back of their minds.

As for the patients, it's not just an uneasiness but fear — bedridden by a virus that may keep them there for a few days or a few months. They fight through that uncertainty in an environment where the constant humming of medical equipment, protective gear, and covered faces of health care workers make it hard to even communicate — in the rare cases there are answers to give.

"We have young people in there anywhere from 20s to 40s that have gotten so sick and died from this," Dr. Elizabeth Middleton said. "And then there are other people in their 90s that come into the hospital and bounce out. So not being able to predict that, that's scary and that's really scary for patients. Once they come to the ICU, they're terrified because this could either go pretty smoothly over the next few days or they could end up on a ventilator and die after five weeks."

Middleton replays the dialogue in her head over and over. One of her COVID-19 patients — an older man, but definitely not one you'd call elderly — had contracted the virus when his grandson visited. Middleton said the grandson got the virus at school and it had made its way through the family with no harm done — until the visit to his grandparents' home.

"He was scared," Middleton said. "I would have conversations with them and I thought that he was going to do OK. Healthy guy — not that old. And he died after being with us for weeks. It was heartbreaking."

Her voice cracked when she spoke about the pain she's witnessed, and then her speech is filled with righteous anger as she pleaded for people to take the pandemic seriously.

The massive Halloween parties that were thrown? That means the ICU staff gets to treat more of those kids' grandparents — or maybe those kids themselves. The people who have refused to wear a mask? More chances for the virus to spread to one of the unlucky people that will have a massive, if not life-ending, effect on in the coming days. The large extended family gatherings? Adding to the time where she can't see hers.

"I don't want to get too much into politics here, but I think there's been a lack of leadership coming from the highest level saying that this is important," Middleton said. "And some people haven't taken it as seriously. But I've got friends who do take it seriously, but they said 'You know what? I don't know anyone who's had this. I don't know anyone who's affected,' so they feel like they're sacrificing for an unknown cause at some level."

It's frustrating for her because as the trivial debate over masks versus personal freedom has gone on, the hospitals have filled up. And as people have thrown around Utah's low death rate (which is thanks to doctors like Middleton) as justifying a return to a more normal life, more patients die.

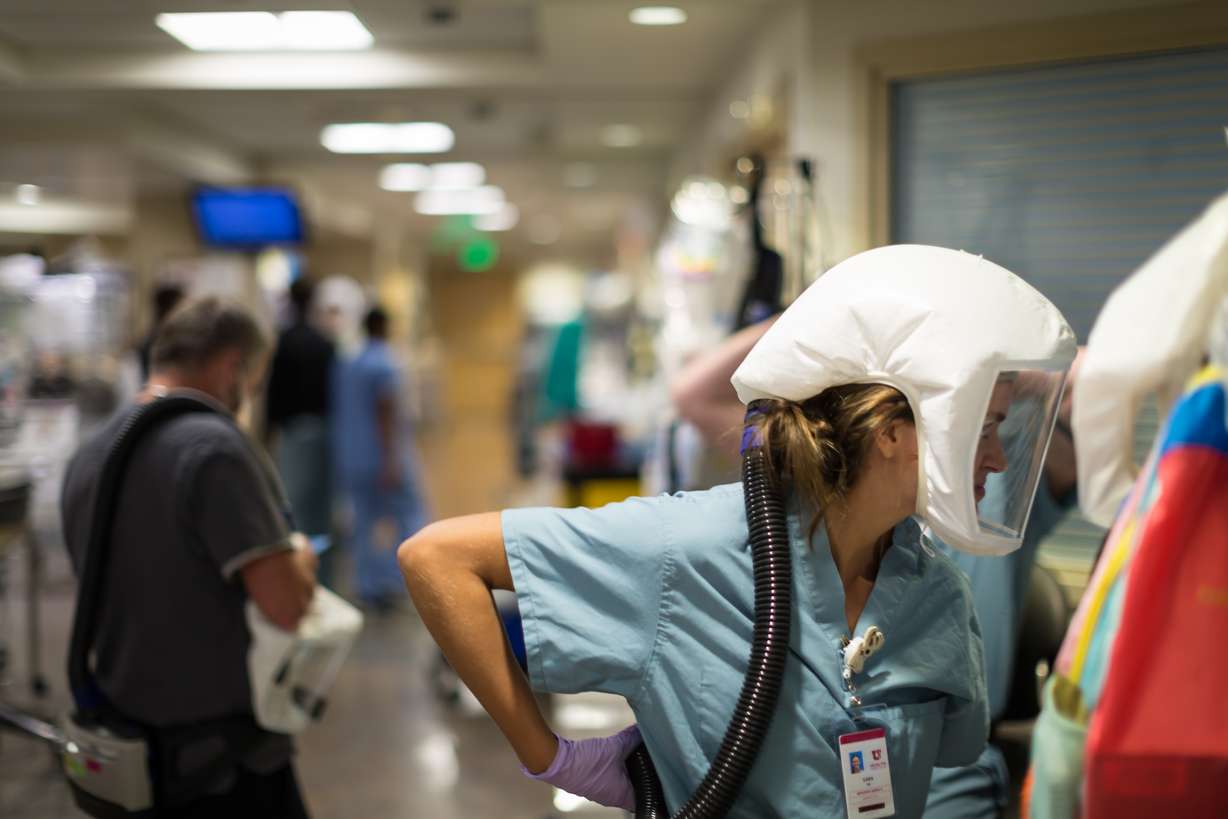

"I've kind of found, and I think people I work with, that you can't really convince people what's happening here," said Courtney Jorgensen, a nurse at the University of Utah hospital's ICU. "I guess if people were to walk through and see, maybe they'd have a better understanding."

So what would they see?

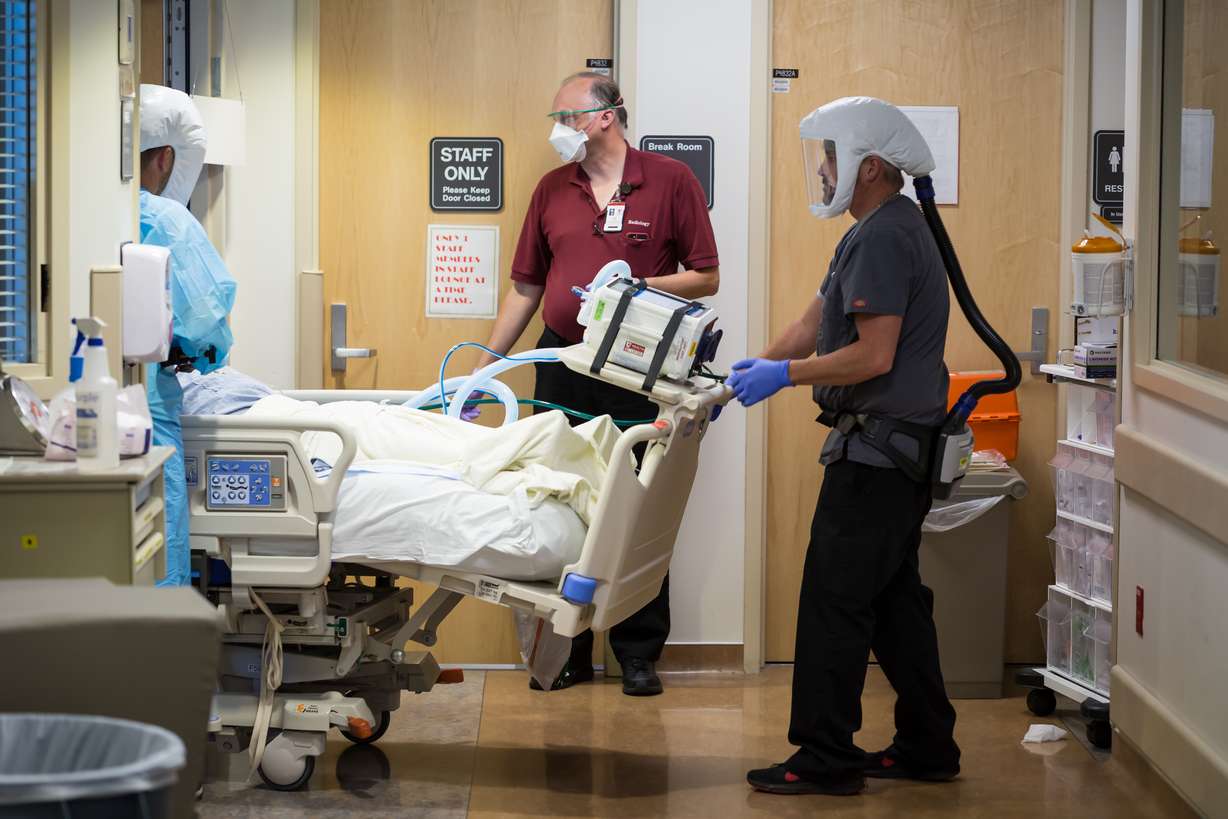

"It's just busy and it's constantly moving and people are physically exhausted," Middleton said. "There's a lot of personnel working with a lot of patients, all the time. It's loud. It's hard to have a conversation because of all the masks and the (respirators) and the noise from equipment and everything."

You'll have to take her word for it since visitors are rarely allowed — and usually only when a patient is reaching the end. So not only are the medical workers physically spent, with nurses having to pick up multiple extra shifts to keep up with the growing cases, and mentally exhausted after fighting the virus for what has now been close to eight months, they also have to be an emotional arm for their patients as well.

"It's really hard. They feel so isolated and they're scared," Middleton said. "And what's really hard is when there's a language barrier."

The hospital has had a large number of Spanish-speaking individuals, as well as people from refugee populations. In some cases, doctors and nurses have had to communicate with patients via a translator app on their phone or tablet. That's hard in a perfect situation. In one where fear and chaos sometimes abounds, it can be near impossible

"When they get really sick, and they're no longer able to communicate directly with their family, and you're trying to be that in between," Middleton said. "Family doesn't trust you, they can't be there, they have no context of what all these machines mean, and they're not there to physically see their patient. A (phone) screen doesn't convey that information."

If there is good news, it's that hospitals are getting better at treating COVID-19. Patients aren't automatically put on a ventilator and there's less concern among the hospital staff about contracting the disease themselves. And with a vaccine seemingly on the way, there may be a day when there is a light at the end of the tunnel.

For now, though, it's still pretty bleak. As part of its contingency plans, hospitals across the state have started converting acute care floors into ICU floors and workers are being repurposed as ICU nurses.

"I think people are just kind of anxious; but at the same time, we have been doing this for eight months," Jorgensen said. "We've been doing this since March and people are burnt out, but we know that we're needed and there's a sense of pride that we can help these patients. We have helped a lot of people get better."