Estimated read time: 7-8 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

SALT LAKE CITY — Workplaces accounted for three-fourths of all COVID-19 outbreaks in the first few months of the coronavirus pandemic, and a new report published by federal health officials shows a significant disparity involving minority workers.

“Hispanic and nonwhite workers are much more likely to be a part of a workplace outbreak and to be infected as a part of these outbreaks,” said Keegan McCaffrey, an epidemiologist at the Utah Department of Health, and one of the study’s authors. “It shows that nonwhite and Hispanic identifying people are at risk, generally, but specifically at these work sites.”

The study, published Monday in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, analyzed COVID-19 data collected from March 6 — the day Utah reported its first COVID-19 case — to June 5. It represents the state’s first three months of data. The state reported 11,448 total cases during that time frame, which is nearly one-fourth of the state’s cases to date.

The report was compiled by members of the CDC, the Utah Department of Health, and six local health departments. It found that 210 of 277 COVID-19 outbreaks in the state during that time — or about 76% — happened at workplaces. A workplace outbreak is defined as two or more COVID-19 cases among coworkers in a shared workplace within a 14-day period. These outbreaks resulted in about 12% — 1,389 in total — of all of Utah’s COVID-19 cases by June 5.

The worst workplace outbreak during the time frame resulted in 79 cases. In all, there were 85 hospitalizations and 40 cases with “severe outcomes” due to these work outbreak cases.

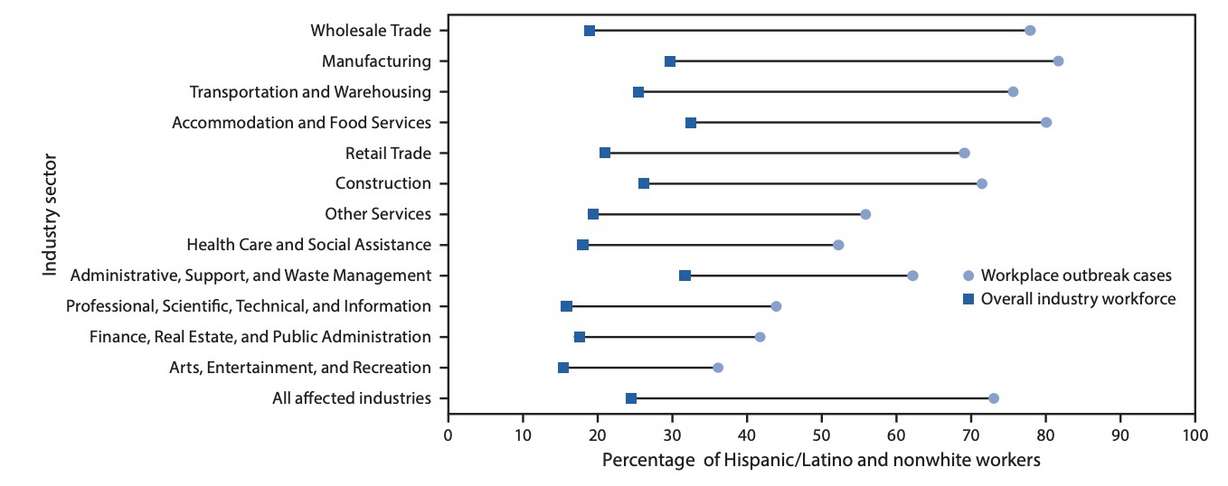

But the most glaring statistic from the report was the difference when it came to race and ethnicity of workplace outbreak cases. Researchers found that Hispanic, Latino and other nonwhite workers accounted for 73% of cases related to workplace outbreaks despite accounting for about a quarter of the workforce within 15 total industry sectors that experienced outbreaks during the time frame.

A racial disparity in workplace outbreaks

It’s not exactly clear what caused the disproportionate shift along racial and ethnic lines, but indications point toward the industry of employment. McCaffrey explained that the researchers not only looked at workplace outbreaks but also what industries they were happening in and who was most likely to be a part of the outbreaks.

Researchers discovered outbreaks all over Utah industries, from restaurants to research labs. But roughly half of the 210 outbreaks fell within three specific sectors: manufacturing, wholesale trade (such as working at a grocery store) and construction. They resulted in 58% of 1,389 total COVID-19 workplace cases. The percentage of nonwhite workers infected in these outbreaks ranged from 72% to 82% of all cases within those respective industries.

“There’s some commonalities between these. First, they’re essential industries that keep our economy moving, that people weren’t able to telework (in), and that were businesses that stayed open through March, April and May when Utah (had more work restrictions),” McCaffrey said.

The study does acknowledge some limitations. For example, outbreaks at smaller businesses may not have been detected or reported, and some industries were working in-person during late March and April while others worked from home. It’s also unknown if coworkers transmitted the virus while at work or outside work gatherings.

That said, the authors of the study noted that similar workplace disparities were found in studies of meat processing facility outbreaks in other states. They theorized that one reason for the divide is that minority workers are more likely to be on essential frontline jobs that Americans depend on but also are high-risk for coming into contact with COVID-19.

“What we see is someone will come to work, infected, pass it to their coworkers, so now we have a worksite outbreak. And then those coworkers will come home and spread it to their family members,” he said. “And some of those family members might then go to a different worksite and start another outbreak.”

It’s easy to blame the worker for coming to work sick, but the study’s authors pointed out that many workplaces had “lack of telework options, and unpaid or punitive sick policy leaves might prevent workers from staying home and seeking care when ill.” They said that ultimately put workers at risk for further exposing COVID-19, delaying treatment, and experiencing worse coronavirus outcomes.

Rebecca Chavez-Houck, a former state representative, as well as a current member of Utah’s Multicultural Commission and Utah's COVID-19 multicultural subcommittee, said the racial and ethnic disparity in data could be due to differences in jobs and households. Not only are minority groups more likely to have frontline essential jobs but they are more likely to live in multigenerational households, where multiple members of the household work essential jobs — creating the cycle McCaffrey explained.

At the same time, many essential workers weren’t getting enough personal protective equipment to stop the spread of COVID-19 while on the job. That added to the concerns brought up from the study about workers not having access to adequate care on time.

“There’s a variety of variables,” Chavez-Houck said. “It creates the perfect storm for continued challenges with exposure.”

Working to close that gap

The findings from Monday’s report add to statistics showing divides in COVID-19 cases by race and ethnicity. Similar disparities are still found within all of the state’s coronavirus cases to date.

For example, the state health department currently reports that Hispanic/Latino, Black/African-American and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander racial and ethnic groups all have COVID-19 rates higher than their respective percentage of the population. The Hispanic or Latino community accounts for 14% of the population and 37% of cases, as of Tuesday. Conversely, the department also lists that the white, not Hispanic or Latino population accounts for 41% of COVID-19 cases despite accounting for 78% of the state’s population.

The authors of the study recommended that health departments and employers improve COVID-19 strategies and messaging so that it overcomes cultural and language barriers and is universally understood. Some of this is already underway with the state providing COVID-19 updates in English and Spanish. There have also been public service announcements and other targeted efforts to inform multicultural communities of COVID-19 risks.

The state health department created a COVID-19 business guide that details prevention and reaction tactics. It’s something that McCaffrey encourages employees to also read so they know how to hold their employers accountable.

“Every employer should have a plan to prevent and then respond to COVID in the worksite,” he said. “Employees should really be advocating for fair paid time off, for being able to social distance at work if possible, or telework.”

Some of the solutions to the COVID-19 racial gap aren’t necessarily quick fixes. That’s because some of what leads to higher COVID-19 rates for minorities are likely the result of socioeconomic factors such as low wages, high housing prices, and less access to health care, Chavez-Houck said. The factors lead to many minority workers taking essential jobs that are high risk for COVID-19; they also explain multigenerational housing may have these high-risk essential jobs.

The other big hurdle is trust, which can be difficult when the government and health agencies are the ones sounding the alarm. As Chavez-Houck points out, many minority communities have been systematically oppressed over time. She said there’s been an improvement in that area but there’s still work to be done.

“If you look within the Latino community — a lot of minority communities — there are reasons why there’s distrust of government information. There’s a long history of why that’s the way it is,” she said. “We’ve had bad experiences. … We’re trying to build up trust by utilizing spokespersons and individuals in the community — business owners, faith leaders, other community leaders — to say ‘these are the things you need to do to keep your community safe.’”

Outbreaks still happening

Despite efforts to mitigate this gap and COVID-19 cases, workplace outbreaks are still occurring. The state now reports 627 workplace outbreaks resulting in 4,283 cases, 184 hospitalizations, and 14 total deaths. A detailed breakdown of these outbreaks from June 6 onward is still being worked on.

Considering the threat that still remains, McCaffrey urges that employees follow the basic guidelines, such as physically distancing if possible, wearing a mask if that’s not possible, and also wearing that mask while on break and between shifts.

He also recommends all Utahns follow the golden rule of the new normal.

“If you are sick, please stay home from work, self-isolate and get tested for COVID if you have COVID symptoms,” he said.

Contributing: John Wojcik, KSL NewsRadio