Estimated read time: 4-5 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

LOGAN — Nearly 350 million metric tons of plastic was produced worldwide in 2017; and while we’re aware of plastic that ends up in landfills or the ocean, a group of Utah State University researchers say there’s an alarming amount of plastic that’s raining down on protected lands in the western U.S. annually.

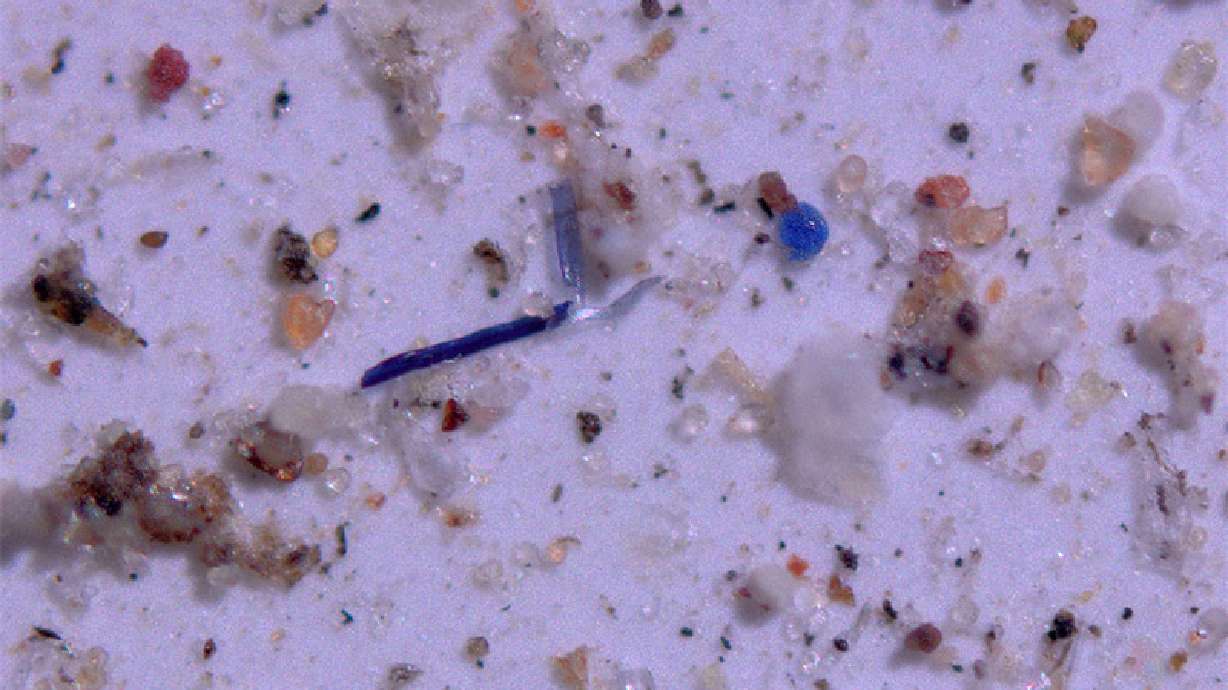

The study was published in Science Magazine Friday. The group of researchers found that more than 1,000 tons of plastic rained down in protected parks they had kept track of during a 14-month period. They say plastics and polymers fragment into pieces known as microplastics that can easily be picked up into the atmosphere in a system similar to the water cycle.

Scientists were already aware that these microplastics were found in all sorts of different bodies of water, but this study’s results stunned researchers said Janice Brahney, assistant professor in USU College of Natural Resources’s watershed sciences department and lead author of the study. The results prompted researchers to go back and confirm their findings through 32 different particle scans, she said.

"The study adds information to what we know about how microplastics move through the environment," Brahney told KSL.com. "There have been a couple of papers that have come out in the last year showing that the atmosphere is a mechanism for plastic dispersal, but we really didn’t have a good sense of where those plastics were coming from, how far they might be traveling, and what their major mechanisms for moving them through the atmosphere were or are."

It’s not just a finding that researchers weren’t expecting; it’s also a research field Brahney didn’t necessarily expect to be in. She’s a biology chemist who focuses on how nutrients cycle through the earth. One of the areas she was studying is how dust moves through the ecosystem — her study was set up to look into that.

But in 2018, she entered the microplastics research field "by accident." While studying phosphorus deposition in dust, she noticed microplastics showing up in samples. Since her study was already designed to look into how particles move through the atmosphere, it was an easy adjustment to make.

She led researchers at USU, Salt Lake Community College and Thermo Fisher Scientific in collecting data at points on protected lands in Utah, Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Nevada and Wyoming. They included national parks like Bryce Canyon, Grand Canyon and Rocky Mountains National Park, but also places like the Uinta Mountains National Wilderness.

The 1,000 tons of plastic figure was calculated from the park areas, which represent 6% of the contiguous U.S. land. Most of the plastics discovered were from clothing or industrial materials. About 30% were brightly-colored microbeads that were likely from industrial paints and coatings, researchers said. They also found that synthetic polymers accounted for 4% of analyzed atmospheric particles located on protected land through those tests.

But the study also dives into how this happens. There are two ways microplastics move through the atmosphere: wet and dry deposition, meaning a microplastic travels through rain or moves through wind.

The researchers found that urban areas with higher populations tended to be the initial source of wet deposition, but secondary sources included microplastics from soils and surface waters that reentered the atmospheres. Dry microplastic deposition, on the other hand, generally comes from much further distances at higher elevations and is influenced by climate patterns.

Plastics, Brahney explained, may have a certain lifetime in terrestrial environments, stay in the soil and get then picked up in a windstorm before being carried long distances in the atmosphere and redeposited in a new location. That new location could be a river or ocean before it ends up in the hydrosphere.

"It does seem as if the plastic cycle is now a thing and cycles through our Earth system analogous to the water cycle or the dust cycle," she said. "What we did find some evidence for is that plastics can be spiraling through the environment."

Brahney acknowledged there are plenty of research angles still to be answered, such as the health implications of microplastics being in the atmosphere. Her team is planning to dive into some of the outstanding questions in the near future.

Since the research was published Friday, news outlets from across the globe have picked up on it. Brahney said the reaction has been a welcome surprise and she is glad that it’s bringing attention to the situation.

"I hope it brings a lot of positive outcomes and more awareness, and hopefully a lot more research on the topics that we don’t understand very well," she said. "Our big finding has to do with plastics that come from both near and far. … It opens up a lot more questions about health and ecosystem health, which we didn’t directly address in that study."