Estimated read time: 2-3 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

Research teams from several universities, including BYU, have pinpointed a cellular motor in our brain that drives the mechanism for memories. The discovery could lead to a way to recharge that motor when it fails.

The mechanism might be compared to a whiteboard. If we need to remember a phone number only long enough to make the call, it's erased shortly after the call is made. But if we need to hold on to a memory forever, it's transferred to permanent storage.

Inside two little areas in the brain called the hippocampus are thousands of cells, or neurons, each containing memory motors.

When we need to remember something, the junction, or synapse as it's called, between the two neurons changes.

More receptors are suddenly delivered to one of the neurons. What drives them there is the memory motor.

"The motor, what its job is, [is] to actually deliver these receptors. They're in a little vesicle, and they are, in a sense, waiting to be moved to these synapses as soon as a stimulation impulse comes in from something you see or hear or smell or taste," explained Dr. Jeffrey Edwards, of BYU's Department of Physiology and Developmental Biology.

All this happens on cellular level we never see, but we experience the payoff.

For example, say you park your car in a huge parking lot, in a sea of thousand other cars. Your brain races to turn on some switches so that when you finish whatever you're going to do and come back, you can find your car.

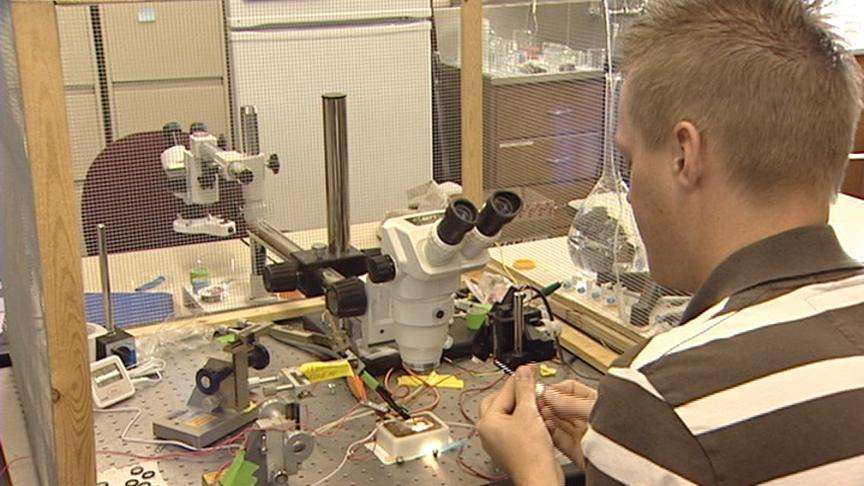

Collaborating with five other research groups, Edwards and his colleagues at BYU recorded electrical impulses from a glass electrode that could actually touch these neurons.

Several years ago, researchers found where the memory receptors come from. Now with the discovery of the motors themselves, teams will search for that which turns them on.

"Theoretically, if you could charge that motor up and get it to be activated more easily, or by lower levels of calcium, which is one of the signals that activates that motor to go into action, you'll have a better memory," Edwards said.

Perhaps this means the possibility of a compound that would recharge these motors as they slow down with age.

E-mail: eyeates@ksl.com