Estimated read time: 8-9 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

Editor's note: Reporter Marjorie Cortez accompanied state officials on a recent trip to southern Utah to chronicle the problems associated with intergenerational poverty and to search for solutions.MOAB — In the sanctuary of a former church now occupied by a nonprofit organization, Moab Mayor Dave Sakrison issues a call to action.

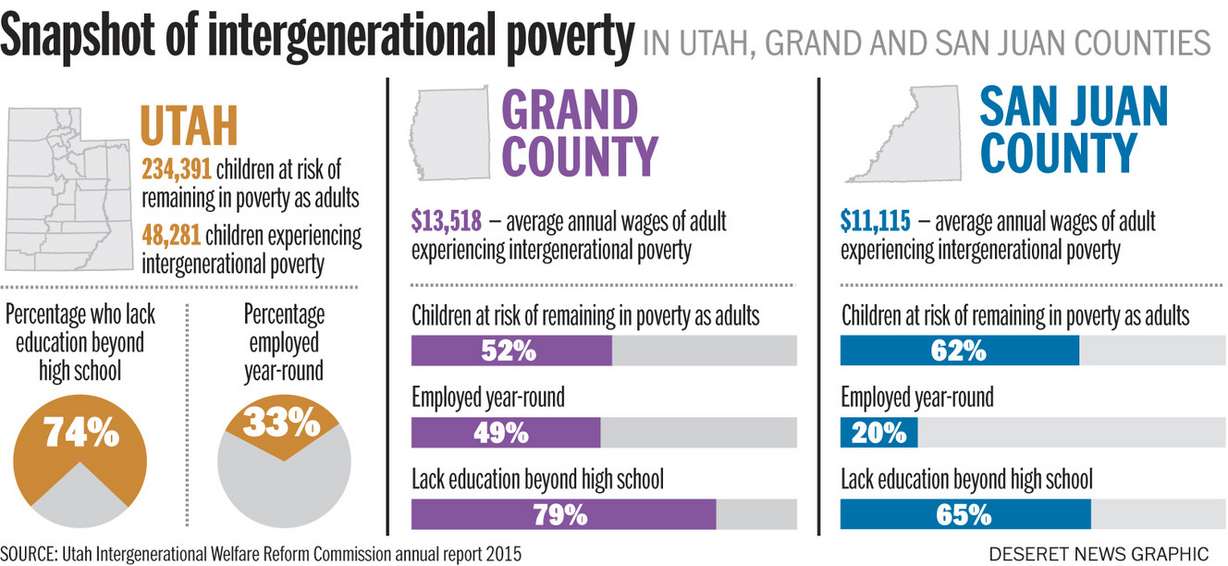

Grand County is among 10 rural counties in Utah where a significant portion of their children are at risk of remaining in poverty as adults, according to the latest annual report of the Utah Intergenerational Welfare Reform Commission.

"We owe it to these citizens, our citizens, to do something about this, to try to break continuation of generational poverty. We owe it to them, and we owe it to ourselves to do this," Sakrison said.

State leaders have been studying public assistance dependency and intergenerational poverty since 2012, after passage of legislation that requires the Utah Department of Workforce Services to produce an annual report on the issues.

In the latest phase of the initiative, state officials are sharing county-level data with local governments to encourage them to develop unique strategies to address these issues within their own communities.

Last week, Lt. Gov. Spencer Cox, Jon Pierpont and Ann Silverberg Williamson, executive directors of the state departments of Workforce Services and Human Services, and other officials visited San Juan and Grand counties to share the history of the state initiative and encourage local approaches to break cycles of poverty and reliance on public assistance programs.

Addressing a packed house at Moab's Seekhaven Family Crisis and Resource Center, Sakrison said Grand County solutions are needed for Grand County's challenges.

"This is a unique proposition. It's not a top down. The state government is not going to solve this for us. We have to, as a community, come together to do something about this, and that’s why you’re all in this room. You’ve got a million ideas, we want to hear them," he said.

According to the report, only half of adults in Grand County who experience intergenerational poverty have year-round employment resulting in an average annual household earning of $13,518.

For the adult cohort — who are on public assistance now and whose households received it when they were children — 39 percent were victims of abuse and neglect.

Among Grand County children experiencing intergenerational poverty, 29 percent are victims of abuse and neglect.

Both categories exceed the state average.

Another worrisome finding for some here last week was that 71 percent of Grand County kids who are part of the intergenerational cohort have had involvement with the state's juvenile justice system.

Sakrison, an Episcopal priest who ministers to Moab's Latino community and has a prison ministry, said he learned about the state report at a rural partnership meeting hosted by Gov. Gary Herbert's office.

"I'll be honest with you. I was astounded. I didn't realize Grand County was in the situation that it was in. I talked to Jon (Pierpont) afterward and said, 'When can you come down?'" he said.

A caring solution

In Grand County, area officials are building upon an existing “Communities That Care” initiative to work on intergenerational poverty-related issues.

Elizabeth Tubbs, chairwoman of the Grand County Council, said for the initiative to succeed, government, nonprofit, business and community partners will need to work collaboratively and communicate better than before.

"While all these programs do wonderful work, we sometimes don’t coordinate very well. We need to utilize what we have and figure out a way to get it together rather than creating something brand new," she said.

Tubbs said she envisions a place or single platform where struggling families can come to find a wide array of helping resources.

"Strong communities require strong families. That’s what that’s all about," Tubbs said.

Cox, who is chairman of the Intergenerational Poverty Welfare Reform Commission and a resident of Sanpete County, said Utahns have a strong tradition of helping one another, evidenced by the nation's highest rates of voluntarism and charitable giving.

When local governments made the call to their communities to come together around the issue of breaking cycles of poverty, community members have packed meeting rooms to lend their support and expertise.

"I believe we can do this in the state of Utah. I believe we can be an example for the rest of the country that is desperate for positive messages and working together as Republicans and Democrats and not hating each other," Cox said.

Intergenerational poverty is defined as two or more generations living in poverty. Statewide, 48,281 children live in intergenerational poverty, according to state reports, while 234,391 are at risk of remaining in poverty as adults.

Most Utah children who live in intergenerational poverty are ages 12 and under, white and live in single-parent households. The majority live in Salt Lake, Utah or Weber counties, although there are children in jeopardy of remaining in poverty in every county of the state, according to state data.

In San Juan County, a White House-sponsored rural impact demonstration project intended to reduce child poverty is already underway.

In November, the county and the nonprofit San Juan Foundation was one of 10 rural counties nationwide to receive a Rural Integration Models for Parents and Children to Thrive (IMPACT) demonstration grant. The grant provides one year of technical assistance.

The goal of the San Juan United initiative is to reduce child poverty using a two-generation approach that serves children and parents together, largely focusing on educational opportunities for both.

One goal envisions establishing one new quality preschool program within targeted Native American communities and one new licensed child care program by the end of this year.

For adults, the initiative seeks to give parents the tools they need to achieve financial stability — financial literacy instruction, high school equivalency and postsecondary education opportunities, as well as job training keyed on workforce needs.

"It’s not just survive, it’s thrive," said Greg Jackson, who is leading the Rural IMPACT Project and serves on the San Juan Foundation board of directors.

While some new programs are planned, other components of the project call for better alignment of existing efforts and programs.

Focus on education

Guy Denton, vice chancellor of Utah State University Eastern's San Juan campus, said its adult education program, which it took over from San Juan School District, is helping significant numbers of area residents finish high school and transition into postgraduate certificate programs, such as truck driving, heavy equipment operation and practical nursing.

"I started out as a high school agriculture teacher years ago, and it was my experience that somebody that didn't have success in public school doesn't want to go back to the public school to get their adult ed," Denton said.

"They have great success because they're able to associate with college students instead of going back to high school. In our developmental classes … in a 15-week class, they have a two grade level gain. That has been great recruitment into our college programs."

This year USU Eastern's San Juan campus awarded 230 associate, bachelor's and master's degrees, said assistant vice chancellor Garth Wilson.

"Seventy five percent of our graduates are Native American," he said.

Denton said USU's programs are nimble and the institution stands ready to assist the efforts of San Juan United.

"We are committed to being part of the solution," he said.

San Juan County Commissioner Rebecca Benally said she believes the county needs to focus on economic development resulting in stable, year-round employment.

Benally said the state report likely does not reflect efforts by the Navajo Nation, which has many initiatives to help more people complete high school and postsecondary education.

"You can educate the heck out of people and they can get degrees. If you're not planning and generating jobs, it doesn't mean a darn thing, and 20 years from now we’ll be standing here and showing the same statistics," she said.

Phil Lyman, chairman of the San Juan County Commission, said he grew up in the area and many people shared the same standard of living. Many of his classmates, including him, wore hand-me-down clothes. There was "no stigma that I was aware of" to utilizing the free or reduced-price school lunch program.

"I had a friend who was a couple years older, a friend of the family and he gave me a box of hand-me-down clothes. I was about 15 and this was in the '70s. The first I'd seen bell-bottom pants was in that box of hand-me-downs. If not for him, I probably would have missed the disco era completely. It was a real blessing in my life," he said, eliciting laughter during the meeting on the university campus.

On a more serious note, Lyman said government agencies and reports track "comparative poverty," how one group compares with others in the county or in the state or in the region.

"I see some dangers in that, especially in a county like San Juan County. People here don’t make a lot of money but they certainly live in a beautiful place and have a rich history and culture. It’s hard to say one group is in poverty. Maybe in one sense they are but they’re extremely blessed and extremely rich in another. Growing up in Blanding, I always felt that," he said.

Still, Lyman acknowledged San Juan County faces many challenges, and San Juan United, under Jackson's leadership, holds great promise.

"He seems to be the right person at the right time with some really important resources he brings to the table," Lyman said.