Estimated read time: 2-3 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

SALT LAKE CITY — Even at the fastest possible speed, that of light itself, it would take you some 4 billion years to traverse what's being called the largest known structure in the early universe.

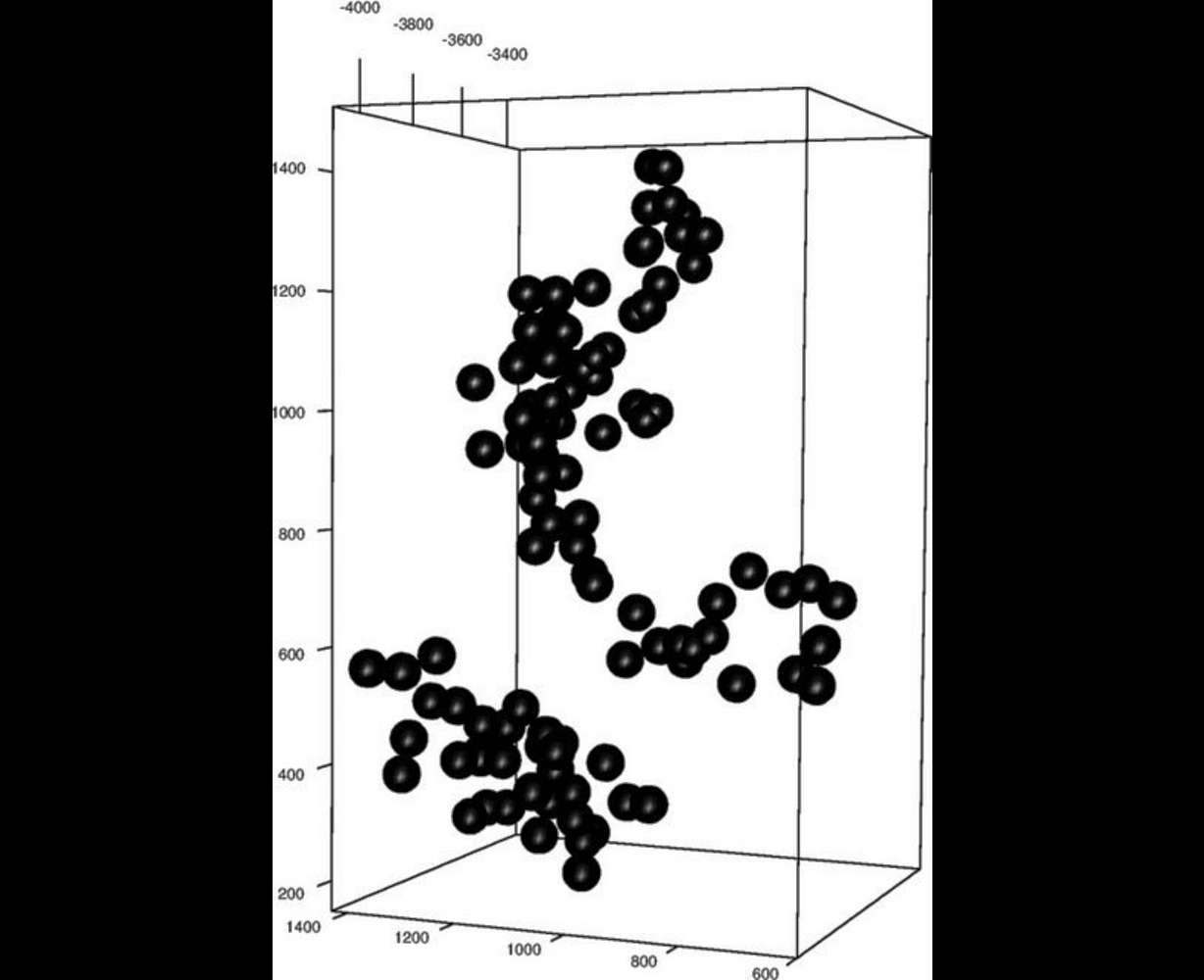

It's appropriately called the Huge-LQG, which stands for large quasar group, and not only is it the biggest thing we've ever seen, its size alone is challenging some important assumptions of astrophysics.

A quasar is essentially the core of a large galaxy at the beginning of its life. It is the galactic equivalent of the pit of an avocado, only it's an avocado that eats itself slowly over the course of billions of years.

Quasars are the furthest and most massive objects in the universe, which makes them important elements in the study of the early history of everything that exists. Their orientation, distribution and size tell us important information about how the universe formed. Like, for instance, whether it is is smooth or bumpy.

Or rather, is matter spread out relatively evenly, or does it tend to clump up together?

The accepted idea is called the cosmological principle. Clearly, clumping occurs, since dense galaxies exist separated by vast distances, but the idea of the cosmological principle is that if you use a large enough scale, the universe appears smooth, with evenly distributed matter throughout.

"(The Huge-LQG) is significant not just because of its size but also because it challenges the Cosmological Principle, which has been widely accepted since Einstein," said lead author Roger Clowes. "Our team has been looking at similar cases which add further weight to this challenge and we will be continuing to investigate these fascinating phenomena."

According to the researchers, led by Clowes at the University of Central Lancashire, the sheer size of the Huge-LQG exceeds the largest scale so far proposed that would make the universe is spread out evenly

To put it another (much more awesome) way, if the universe is evenly distributed, then the largest objects shouldn't be bigger than about 370 megaparsecs across. On the other hand, the Huge-LQG is about 1200 megaparsecs across its largest dimension.

If the cosmological principle held, at least for that scale, there should not be a structure this large, they argue. In short, they think the Huge-LQG means the universe is bumpy, by definition, and there's no "homogeneity" on any size scale.

Not all people are on board however. A Harvard astrophysicist thinks it's too early to say whether their concerns about the cosmological principle are well-founded.

"Is the structure larger than models predict? The answer may well be yes," Margaret Geller of the Harvard Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics told USA today. "Does it show that the cosmological principle is wrong? Probably no. This structure is still small compared with the universe as a whole. It may simply mean that the scale where the principle applies is simply larger than we thought."