Estimated read time: 8-9 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

SALT LAKE CITY — Birds, flying through the air, navigate the world at a much higher rate of speed than land animals, and during their flights they often encounter obstacles. Because of this, eyesight — critical for safe flight — is the most important sense for birds. And birds have developed a number of adaptations that make their visual acuity superior to that of other vertebrates.

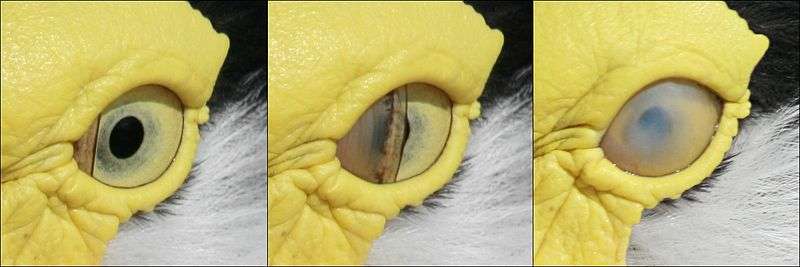

The basic internal structure of a bird’s eye is similar to other animals, but they contain several adaptations unique to birds. Birds have two eyelids, but they also have a third transparent membrane, called a nictitating membrane. Birds don’t blink with their eyelids, but they lubricate their eye by moving the nictitating membrane across their eye. Aquatic birds can also close the nictitating membrane across their eye while diving or swimming, allowing them to see under water.

David Haskell, Professor of biology at Sewanee University and author of “The Forest Unseen,” says that the primary advantage of the nictitating membrane is that birds can clean their eye during flight without obscuring their vision, even temporarily.

In addition, birds secrete an oily substance across their corneas from a gland called the Harderian gland, which protects the eye from dryness during flight.

Birds have large eyes relative to their size, and because of that, most birds can’t move their eyes. Bird eyes are larger than other vertebrates because they contain a lot of extras that other vertebrates don’t have. If a bird wants to look up, down or to the side it has to move its head in that direction to do so. But, most birds, due to some anatomical differences in their eye, have a significantly wider field of view than other vertebrates.

A mammal’s eye is spherical. A bird’s eye has a flatter shape, which enables more of its visual field to be in focus. But, due to this flatter shape, night vision in birds is often greatly reduced. The absorption of light is partly due to the distance between the lens and the retina; the closer the two are, the less light can be absorbed. This forces those birds with that particular feature (which is most birds) to be diurnal.

The bird’s eye is held in place, and held rigid, by a bony plate that circles the eye called the sclerotic ring. Many reptiles also have sclerotic rings. In addition, in most birds the lens lies further forward than mammals or reptiles and this increases the size of the image on the bird’s retina. Birds that have eyes on the sides of their heads possess a very wide field of vision, which helps them detect predators.

The avian eye has ciliary muscles, which are attached directly to the lens by means of zonular fibers, which the bird flexes, or relaxes, to change the shape of the lens, and by so doing changes the eyes’ focus. Reptiles also have ciliary muscles. In addition, some birds also have a second set of muscles, called Crampton’s muscles, which change the shape of the cornea, giving birds a broader range of accommodation that is possible for mammals.

Birds have far more photoreceptors in their retinas than other animals. By comparison humans have about 200,000 receptors per square mm, a sparrow has about 400,000, and a buzzard has about 1 million. This give birds a much higher visual acuity than other animals. This allows foraging birds to detect food sources that would be hidden to us. Where humans see a smooth twig, a chickadee can see insects ensconced in the twig’s cracks, says Haskell.

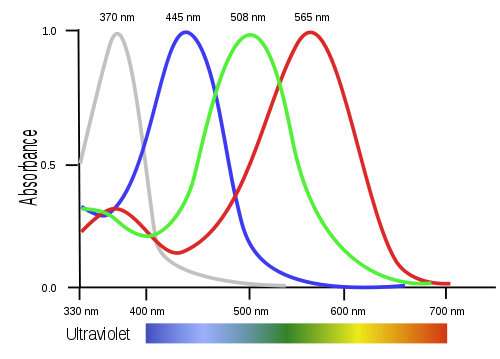

Perhaps the most amazing adaptation of bird vision is that their eyes possess four types of color receptors, called cones. This enables birds to perceive not only the visible range we’re familiar with, but also the ultraviolet part of the spectrum. Humans have three types of cones, most mammals have only two types of color-receptive cones.

“The extra cone allows birds to see into the UV range of the spectrum,” Haskell said. “Light that is invisible to us is visible to them. This not only opens up a new primary color for them, but also allows new combinations with other primary colors. Thus they can see colors that we cannot even imagine.” (What?! Are you kidding me? That is amazing!)

Being able to see the ultraviolet end of the spectrum has some distinct advantages. Some fruits and berries reflect UV light, which makes them very easy for foraging birds to detect. Common Kestrels use their ultraviolet vision to hunt. One of their favorite preys is a vole, which leaves trails of urine to mark their path. Urine reflects UV light, making their paths stand out like a neon sign. The Kestrels simply follow the glowing pee trail to the voles.

Other groups of birds, such as Blue Tits, and Blue Grosbeaks use their ultraviolet vision during courtship. Many birds have plumage that’s visible in ultraviolet, but invisible to the human eye. The male Blue Tit has a crown patch that reflects UV light, which they display during courtship. Bills of blackbirds are also UV-reflective, and studies indicate that the more highly UV-reflective a male blackbird’s beak is the more strongly a female blackbird responds to its courtship.

Some bird species, particularly migratory birds, have adaptations that allow them to detect polarized light, and even magnetic fields. The right eye of a migratory bird contains cryptochromes, which are photoreceptive proteins. Light hitting the cryptochromes produces unpaired electrons. These unpaired electrons seek other electrons to pair with. The unpaired electrons produced in the bird’s cryptochrome pairs with the electrons given off by the Earth’s magnetic field, and thus the bird can “see” it (it might be more accurate to say that the bird detects it). Migratory songbirds are able to migrate such great distances because they can “see” the Earth’s magnetic field, and polarized light patterns and determine their migratory direction. (What?! That’s the coolest thing I’ve ever heard of!)

Most bird groups have specific visual modifications directly linked to their niche in the ecosystem. Birds of prey have a high density of receptors and the more receptors an animal has, the better it can distinguish objects in the distance.

Their eyes are positioned at the front of their heads giving them good binocular vision, and highly accurate depth judgment. Birds of prey are active during the day because their eyes are specially adapted for spatial resolution rather than light gathering, so they function poorly in low light.

Nocturnal birds have tubular eyes, which allows them to gather more light. Most birds have flattened eyes, which greatly increases their field of vision, but greatly decreases their ability to gather light. The greater the distance between the lens and the retina, the more light can be absorbed. Nocturnal birds also have larger corneas, allowing more light to enter.

It is the retina that processes light and color information. Rods process light and cones process color. Nocturnal birds have a low number of color receptor cones, but have a high density of light-absorbing rod cells. The retinas of birds that are active during the day have 80 to 90 percent color-absorbing cones, whereas the retinas of nocturnal hunters, such as owls, are about 90 percent rods.

The retinas of many nocturnal birds contains a tapetum *lucidum*, a layer of tissue in the eye that reflects light back onto the retina, basically giving the retina the ability to twice absorb available light. One known bird species, the oilbird, echolocates like bats.

All birds, except raptors, possess red or yellow oil drops in their color receptors which acts as filters, removing certain wavelengths, and thus improves contrast, and sharpens vision — particularly in hazy conditions. The droplets, which contain high levels of carotenoids, are placed so that light passes through them before reaching the visual pigment. Seabirds and fishing birds possess larger than usual amounts of red oil in their photoreceptors, which allows the bird to see into the water, the same as humans wearing polarized lenses.

Reptiles also contain these same yellow and red oil droplets in their eyes, and it’s believed that mammals had them at some point.

Birds can perceive movements so rapid they would appear as blurs to humans. Humans can perceive movement no greater than 50 Hz. Birds can perceive movement at close to 100 Hz. What this means is, if humans passed through a forest at the rate of speed at which a bird flies it would be one big blur to us, but to a bird it’s not. In addition, some birds — particularly migrating birds — can detect movements very low on the Hz scale, such as the movement of the sun or constellations across the sky. To us, such slow movements are imperceptible, but birds notice such slow movements, and it’s believed that they use this information to orientate themselves.

If you have a science subject you'd like Steven Law to explore in a future article send him your idea at curious_things@hotmail.com.