Estimated read time: 5-6 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

SALT LAKE CITY — The summer heat is alive and well with temperatures flirting with 100 degrees in Salt Lake City and blowing past 100 in St. George. Lemonade, swimming pools, shade trees and water parks are all popular ways to stay cool, but none of them match the convenience of air conditioning. How do they do it?

All air conditioning systems are based on the process of heat transfer, regardless of the methods used to cool the air. Air conditioning is defined simply as the removal of heat from indoor air to achieve thermal comfort. The effort to achieve and maintain that comfort has been a part of the human condition for centuries.

To understand the science of air conditioning, it’s helpful to review the history. The first record of a system for cooling air was found to be in ancient Egypt as thick mats made of reeds arranged with water trickling down to provide evaporative cooling. Slaves often provided the fan power to move the air across the mats. In ancient Rome, water was circulated through the walls in some houses to cool them.

About 180 AD, the Chinese invented the first mechanized rotary fan to provide heat transfer through the passage of air to cool rooms. All of these examples are based on natural phenomena that is governed by the laws of thermodynamics as systems designed to transfer heat from one area to another.

In 1758, Benjamin Franklin and John Hadley, scientists in every sense of the word, experimented with various liquids to apply direct evaporative cooling to an object, starting with alcohol and ether. With this experiment, they were able to demonstrate rapid cooling using evaporation of a volatile liquid from a warm object.

Air conditioning systems can be defined in two broad groups: refrigeration cycle units also known as heat pumps and evaporative cooling units better known as swamp coolers.

Heat Pumps

Mechanical cooling on a large scale didn’t appear until 1902 with the introduction of the first modern electrical air conditioning system by Willis Haviland Carrier. The name sounds familiar, doesn’t it? Carrier’s name can be seen on rooftops the world over as a large, vented beige box, with lots of noise emanating from within.

Carrier’s system employs principles embodied in the refrigeration cycle. The refrigeration cycle is the process of the evaporation, compression and condensation of a volatile liquid to transfer heat from one area to another.

Starting with a compressed liquid refrigeran t, the liquid is released through an expansion valve into a set of coils called the evaporator. In the evaporator, the liquid absorbs heat and evaporates as air from the area is forced through the coils with a fan. This cools the air.

Then the refrigerant gas is compressed and sent through another set of coils called the condenser. Another fan blows air from outside of the area to be cooled across the condenser coils to cool and condense the compressed gas into a liquid again. The cycle is repeated after the gas is condensed into liquid.

The laws of thermodynamics can be used to describe the entire process of refrigeration and can also be used to design optimal systems for refrigeration. Materials like copper are used in coils because copper is an excellent heat conductor. Insulators such as fiberglass and rubber are used to prevent unwanted heat exchange with air surrounding ductwork, piping and mechanical equipment such as air conditioning units, evaporators and condensers.

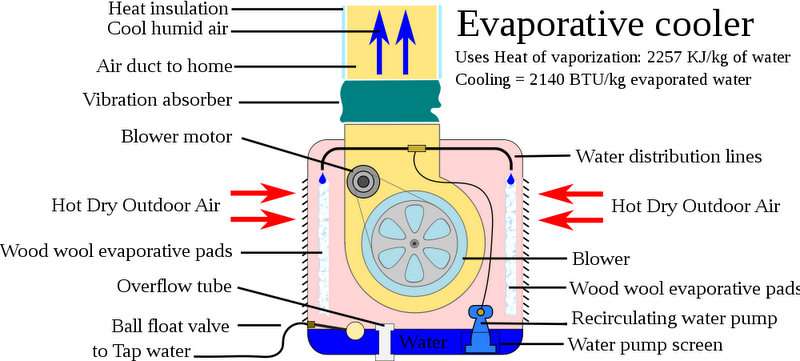

Swamp Coolers The wet mats employed by the ancient Egyptians combined with the rotary fan from China give us the foundation for the modern evaporative cooler, also known as the swamp cooler. Swamp coolers are common in Salt Lake City and are easily recognized as a vented box on the rooftop. Behind the vents is a mesh that is designed to withstand constant exposure to water and air for long periods of time. The mesh fills the role of the reeds that ancient Egyptians used in their early evaporative cooling systems.

Inside the swamp cooler is a squirrel cage fan that pulls air from the outside, through the mesh in the walls of the cooler. The air is cooled as it is pulled through the mesh, evaporating water as it passes over the water. The squirrel cage fan pulls air through the walls and forces cool air into ductwork that distributes the air through the area to be cooled. The typical swamp cooler can drop the temperature of outside air by as much as 20 degrees.

The basic technology and science of air conditioning hasn’t changed very much over thousands of years. Today’s air conditioning systems still use evaporation of liquids to efficiently transfer heat. Fans are still used to force air through a medium of exchange such as copper coils or a wet mesh.

For much of the last century, most of the refinements in air conditioning equipment relate to improvements of the controls, materials, construction and incremental improvements in design. Hence, the basic elements of the design of the swamp cooler and the air conditioning unit have remained essentially the same, employing the same scientific principles for more than 100 years.

Scott Dunn is an IT technology worker and writer, living in the Salt Lake City area.