Estimated read time: 3-4 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

SALT LAKE CITY — From explosions in the sky (not the band) to crabs the color of kids bubble gum, scientists have been busy working on some extremely interesting (and possibly undead) discoveries.

Purple crabs discovered in Philippines

It's like a 1980s 8-bit video game has come to life: Scientists from the Senckenberg Research Institute have discovered a bright purple grab that only lives on the small Palawan island group in the Philippines. The crab, called insulamon magnum, along with three other brightly-colored new species, are endemic, meaning that they can't be found elsewhere. Because insulamon magnum requires fresh water, it can't leave the islands.

It's theorized the colors indicate to other crabs important social information like age, sex and species, since it has been shown that crabs can distinguish some colors.

The discoverers are worried about the fate of the crabs, as well as much of the rest of the life on the Palawan islands, because drilling threatens the species there. About half of the species on the islands can't be found anywhere else in the world.

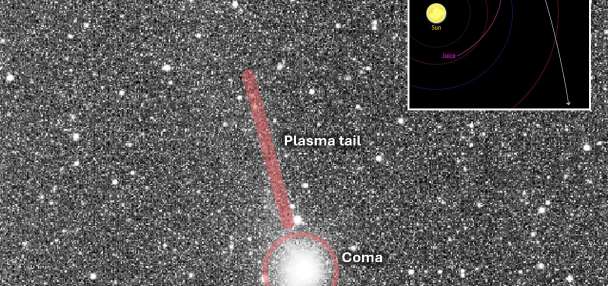

Minivan-sized meteorite explodes over California

NASA has determined that the explosion seen in broad daylight over parts of California and Nevada Sunaday was caused by a meteor about the size of a minivan. "Most meteors you see in the night's sky are the size of tiny stones or even grains of sand and their trail lasts all of a second or two," said Don Yeomans of NASA's Near-Earth Object Program Office at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. "Fireballs you can see relatively easily in the daytime and are many times that size - anywhere from a baseball-sized object to something as big as a minivan."

The explosion was about the size of a 4 kiloton bomb - that's roughly 8 million pounds of TNT or half the size of a small atomic bomb.

No damage was apparent as a result of the meteor, but the event is fairly rare. An object that size comes through the atmosphere perhaps once a year, but is usually over an ocean or an uninhabited area and is never seen.

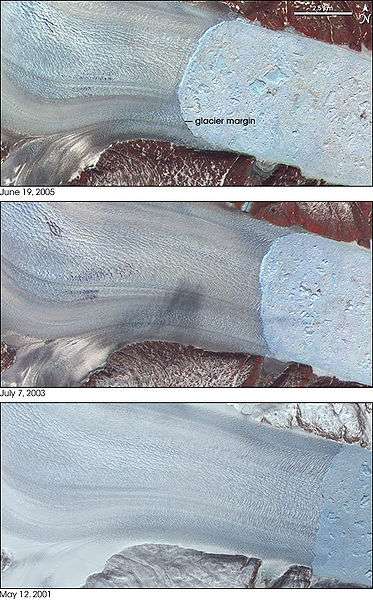

Zombie microbes released by thawing polar ice caps

Well, not precisely zombie microbes, but really old bacteria and viruses that have never been seen before and have been out of the ecosystem for anywhere between thousands and millions of years are in the verge of a comeback as the Earth's ice melts.

Antarctic researchers have found living bacteria in ice at the poles. Many frozen bacteria are in a sort of suspended animation, and can be revived if conditions are right.

According to

It could even release a pathogen that affects humans directly, though that's not likely.

"The chances aren't zero," Scott Rogers, an evolutionary biologist at Bowling Green State University, told Scientific American "but they're very close to zero."