Estimated read time: 4-5 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

HIGHLAND — The parents of three teenage students who committed suicide took the stage at Lone Peak High School this week to share their children's tragic stories and urge parents to get involved before another life is lost.

It was a poignant and emotional conversation and provided stark contrast to the way suicide is often dealt with: quietly and privately, often without police press releases or media attention. But with suicide the second highest cause of teen death in Utah, it is a problem many say can no longer stay in the shadows.

"It's not a subject that gets the treatment it needs anywhere," said Sheila Crowell, an assistant professor in the psychology department of the University of Utah. She said there is relative silence surrounding depression and suicide, issues that have surfaced in Utah in dramatic fashion during the past year.

In addition to the Lone Peak students, two Alpine School District students committed suicide and one died of an overdose in the fall. In late February, two Clearfield High students died of suicide within days of each other.

She said there is a lingering stigma surrounding mental and emotional health as well as a general unease by people not knowing how to help. It is also difficult for those with depression to approach others about their need for help.

It's not a subject that gets the treatment it needs anywhere.

–- Sheila Crowell, U. of U.

"Many people fall into the well of emotional despair and don't know how to get out," she said.

Don Watkins, one of the parents who spoke at Lone Peak, said Thursday his daughter Micah suffered from different mental challenges since she was born. She died in January, after years of therapy.

"At the end of the day we don't feel guilty as parents," Watkins said of he and his wife Peggy. "It was three years of trying everything we could do."

Now he wants to help others, and he said more information is needed to combat speculation and false ideas regarding mental illness.

"We want to do anything we can to help," he said.

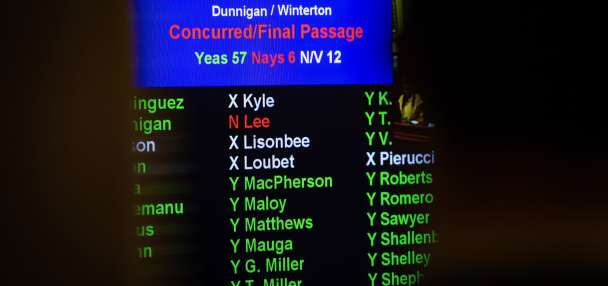

The Clearfield deaths came in the middle of the 2012 legislative session, when lawmakers voted in favor of a bill requiring two hours of suicide prevention training every five years for public education employees. That bill was signed into law on Monday and will further the public conversation.

Justin Keetch, assistant director of student services for Alpine School District, directs Alpine's crisis intervention team. He said the biggest concern when responding to a teen suicide is the risk of copycat incidents. To overcome that, teams try to focus on the person and not on the manner in which they died.

Many students have suicidal thoughts, and crisis teams work to help a student body deal with loss without giving credence to the idea that taking one's life results in an outpouring of love and affection from others.

After the first death at Lone Peak High School, students began a spontaneous memorial with photographs and notes. Keetch said the memorial was moved inside, to the school counseling center, where grief could be expressed near help and with counselors available to offer perspective.

"We really recognize that students do need to grieve, but just as we don't want to vilify the student because they died by suicide, we don't want to glorify the choice," Keetch said.

We really recognize that students do need to grieve, but just as we don't want to vilify the student because they died by suicide, we don't want to glorify the choice.

–- Justin Keetch, Alpine School District

Crowell said Lone Peak was a good example of striking the balance between grieving and glorifying and complimented the team for its decision to move the memorial. She said copycat incidents are a concern, but talking with people about suicide and asking them about suicide does not increase risk.

Crowell said for a parent, asking a child if they've considered suicide is one of the hardest questions to ask but also one of the most important.

"The number one thing is talk to your kids," he said. "Talk to your kids about everything, as much as you can."

Crowell said it is unclear how common self-injury is, but national studies of college students show rates as high as 35 percent, with higher- risk groups at 45 percent.

"It's probably happening in a lot more homes than people realize," she said.

The family is not the only group that shies away from conversations on suicide. Suicide is not reported as frequently as other deaths by law enforcement agencies and media outlets.

Tom Haraldsen, president of the Utah Headliners Chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists, said that with any tragedy, journalists weigh the public's right to know with sensitivity for victims.

"I don't think it should be ignored but it shouldn't be exploited," he said.

He said media reports on suicide often stem from a family's desire to come forward and use the victim's story as a cautionary tale. Some families, he said, appear to expedite the grieving process by sharing the life of their loved one.

But grief hits everyone differently, he said, and when families choose not to volunteer the information it becomes a question of how far a journalist should go to tell the story.

"With teen suicide being a problem, yes, I do think as journalists we have a need to talk about it," he said.

Email:benwood@desnews.com