Estimated read time: 6-7 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

SALT LAKE CITY — Spiders are ancient creatures, dating back some 380 million years to the early Paleozoic. Scientists have classified more than 40,000 different spiders, and all of them make silk at some point in their lives. Silk is vital to their survival and reproduction.

Spiders use silk in many different ways. It’s used to wrap their eggs, catch prey in their webs, create protective retreats and as a trailing safety line as they move about.

“One of the unforgettable moments in my life was the first time I dissected a spider and saw its stunningly beautiful, translucent silk glands,” said Cheryl Hayashi. Hayashi is a professor of biology at UC Riverside. She has been studying spiders and spider silk for more than 20 years. She has delivered numerous talks about spider silk, including on TED Talks and CNN.

“For me, each day begins and ends with wanting to learn a little more about the secrets of spider silk,” says Hayashi.

Most spiders produce several different types of silk, said Hayashi, and each type of silk is used for a specific purpose. A common garden spider can make seven different types of silk. Each silk is chemically and functionally distinctive.

For each type of silk a spider makes, it has a silk gland inside its abdomen that makes that specific type of silk.

A spider will often use more than one type of silk on a project, according to Hayashi. “When you look at an orb-web, there’s one type of ultra-strong and fairly stiff silk that makes up the scaffold,” she said. “The sticky spiral of the orb-web is composed of two different silks, one a glue and the other a highly stretchable fiber. The glue and fiber are produced in separate glands and the spider dots the glue onto the fiber while building the web.”

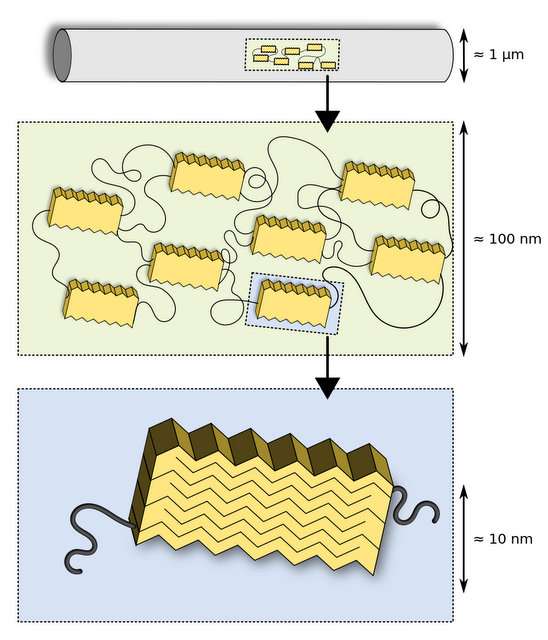

The silk is made in the silk glands and emerges from a spider’s spinnerets, which are located near the rear of their bodies. Inside the spider’s body, the silks are stored in a highly concentrated, liquid form. A typical spider has six spinnerets in three pairs, and each spinneret has many spigots. Silk emerges from the spigots, and each spigot is connected to its own silk gland. All of these individual threads emerging from the spigots then come together into a single thread.

Spiders are able to spin silk from the time they are babies. “The eggs hatch inside the egg sac and the spiderlings go through a few molts, and then they are ready to leave the egg sac,” Hayashi said. “Prior to leaving the egg sac, spiderlings are able to make silk. It’s adorable to see a bunch of baby spiders outside of their eggs sac, hanging out on teeny- tiny silk threads.”

The silk from spiders is different than the silk from a silkworm. “Silk used in textiles is spun from the mouths of caterpillars to form cocoons that protect them while they transform into moths,” Hayashi said. “A silkworm has only one pair of silk glands and can make only one type of fiber.”

Spider silk is a made from a continuous chain of protein fibers. The different types of silk are differentiated by their sequence of amino acids, which consist mainly of glycine and alinine blocks.

Other compounds are used to enhance the silk. For example, pyrrolidine keeps the thread moist, and potassium hydrogen phosphate embedded into the silk makes the thread acidic (a pH of 4), which protects it from fungi and bacteria.

Both male and female spiders continuously make silk, and drawing it out of the glands stimulates them to make more. In labs, scientists have manually drawn silk from a spider and can occasionally collect more than 100 meters in about 10 minutes, according to Hayashi. Constructing the web is a tricky and delicate bit of work. Paul Hillyard, author of "The Book of the Spider," explained how an orb-web is built.

To begin the construction, the spider makes some silk line, usually the finest, lightest silk line it is able to produce. Using a breeze, the spider floats its line across the gap where it wants to span its web.

As soon as the spanning thread adheres to an object across the gap, the spider pulls the thread tight and runs across it, trailing more thread behind it. It crosses back and forth across the spanning thread several times, making a strong cable.

Then, from the middle of the bridge thread, the spider attaches a line, drops down and fixes it below, Hillyard said. It pulls the descending string down very tight, pulling the bridge thread down dramatically so that the descending thread and the bridge thread make a Y. The center of the Y becomes the center of the spider’s web.

Next, the spider makes many more radial threads, which meet at the center of the web and radiate outward and attach at different objects on the perimeter. An orb web will have from 10 to 80 radial threads, depending on the species of spider.

Each radial thread is produced twice, Hillyard said. The first thread is temporary as the spider moves from the center of the web outward. Once the spider has reached the object it wants to attach its web to, it crawls back to the center of the hub, along its original line, trailing more silk. When the spider reaches the hub, it pulls the second line taut and fixes it to the hub. It cuts and disposes the first line.

The spider next attaches the radial threads together with a spiral line. Again the spider lays down a temporary spiral first. The spider begins at the web’s hub and moves outward toward the outer edges of the web, tying the radial threads together as it goes.

The spider returns to the center of the web, using the line it laid down as a guideline. On its second pass, the spider lays down the permanent line — which is sticky — simultaneously cutting out the temporary spiral. It’s this sticky line that catches the prey. The spider typically leaves the center of the hub free from sticky threads, giving itself a space where it can freely roam without getting caught in its own web.

Only the spiral part of the web is sticky. The spokes are not sticky. The spider, when moving across its web, will avoid the sticky parts of the web. But even then, the spider will occasionally come in contact with the sticky part of its web.

A spider’s legs are covered with tiny hairs. When the spider touches the sticky line with its hairy leg, as it pulls away the glue drips down the hairs and that leaves very little surface area between the web’s glue and the spider. That reduces the glue’s pull. In addition, a spider legs are covered in an oily coating that reduces the adhesion further.

Spiders live about a year on average, but some species live for only a few months. Some species of mygalomorphs (e.g. tarantulas, trap-door spiders) can live for longer than 20 years.

If you have a science subject you'd like Steven Law to explore in a future article send him your idea at curious_things@hotmail.com.