Estimated read time: 7-8 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

SALT LAKE CITY — It's really no secret as to why the eastern portion of Salt Lake City has a few thousand more trees than the west side, says Kelsey Lindquist, a city planning manager.

The Avenues, East Bench and Sugar House neighborhoods have about twice as much urban forest canopy as the northwest and west side master plan map areas altogether, according to 2014 city data. She says this disparity dates back to a housing tactic, known as redlining, that existed nearly a century ago and aimed to keep minority homeowners out of desired parts of the city.

"The (historically desirable areas) have between two and six times the tree canopy as the ones redlined," Lindquist says, adding that similar issues emerged in other cities that practiced the now-illegal discriminatory housing practices.

But there's a reason why this matters all these years later. These trees, a part of the city's urban forest, are widely considered vital pieces in environmental health and planning design. The U.S. Forest Service, for instance, touts urban forests as "critical benefits to people and wildlife," especially as the country became more urbanized through population growth and development.

"Urban forests help to filter air and water, control stormwater, conserve energy and provide animal habitat and shade," the agency writes. "They add beauty, form and structure to urban design. By reducing noise and providing places to recreate, urban forests strengthen social cohesion, spur community revitalization and add economic value to our communities."

It's why Salt Lake City planners are looking to improve tree cover across the city through the Urban Forest Action Plan, which was first brought to the public's attention in 2020. Members of the planning team presented an update on the project during a Salt Lake City Council work session Tuesday held at the Sorenson Multi-Cultural Center & Unity Fitness Center on the city's west side.

Nick Norris, Salt Lake City's planning director, told KSL.com on Thursday that plan is all but done now and will likely be submitted to the city's planning commission in September before it's up for the council's final approval, which may come as early as the end of this year.

Why care about urban forests?

The action plan emerged out of ideas sparked by a 25-year vision plan the city compiled in 2015. The first document notes that city's urban forest isn't just an important environmental tool but one that is favored among residents, which is driving the plan to expand the urban forest.

City planners then collected a score of public comments through surveys and public meetings that helped craft the plan after it was announced two years ago. It resulted in a 106-page initial draft plan that was made public in late March.

The plan aims to increase the urban forest more equitably so that the historic divide in trees can be closed. Norris says a net gain of about 3,300 trees would even out the difference of trees on the west side today.

But there are also other goals outlined by the city, including:

- Ensure there's adequate protection of the urban forest as a public good through land use policy and land management practice. This may include trees dictating future landscaping policies

- Codify the city's commitment to sustainable infrastructure

- Value the urban forest for the entire range of ecosystem and quality-of-life benefits it provides

- Provide solutions in the right-of-way that will accommodate trees, access and utilities where they compete for the same space

- Guide urban forest priorities and preservation for project reviewers and inspectors

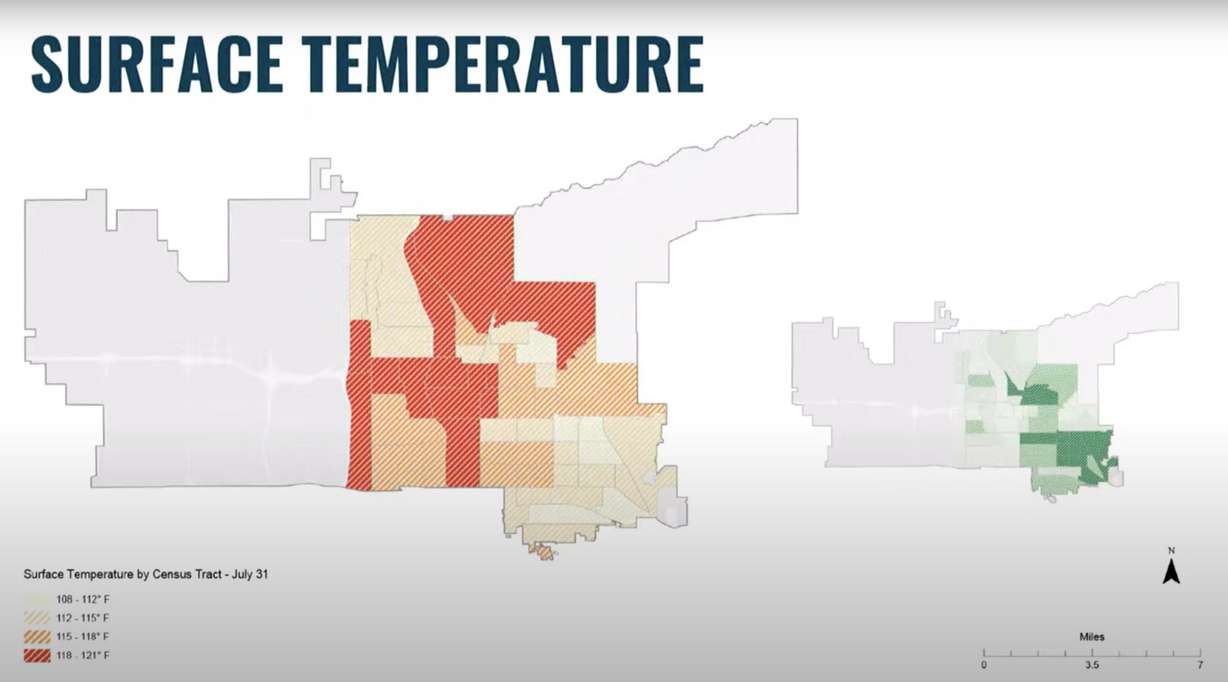

City planners believe that the urban forest is important in addressing the environmental impacts of climate change but also the city's record growth, which continues to add development and potentially remove trees. Surface temperatures are generally hotter in parts of Salt Lake City without trees, aside from the Capitol Hill area, which Lindquist says is a result of its west-facing slopes and "compact industrial uses."

This is why it's often as hot in downtown Salt Lake City as it is by the Salt Lake City International Airport and the city's northwest quadrant. Lindquist says this is also where the tree shortage on the west side is evident, resulting in some communities dealing with urban heat island effect.

"While this effect is due to a complex interaction of variables, looking at surface temperatures gives us a good idea of which areas of the city need shade and cooling," she said. "The correlation between the redline districts and surface temperatures is striking."

Meanwhile, she adds the right trees have the capability to help address the city's ozone pollution issues, which she calls "the biggest contributor to poor air quality during the summer." Ozone is formed when pollution from vehicle emissions and industrial sources mix with sunlight and heat; the American Lung Association ranks the Salt Lake City-Provo-Orem metropolitan area as having the 10th-worst ozone levels in the U.S.

Studies have shown lower childhood asthma rates in areas with more trees, which is partially why asthma may be more prevalent on the city's west side, too. City data show higher rates of childhood asthma on the west side along with lower rates of health insurance.

"The disparity matters because it correlates to continued adverse public health outcomes, reduced livability and decreased resilience within the face of climate change," Lindquist said.

What about the drought?

Planting new trees isn't all rosy, though. The draft report acknowledges there are a handful of challenges to consider with the urban canopy because of changing climates, noting that exposure to disease, pests and extreme weather events are expected to increase "stress on trees."

Tony Gliot, the city's urban forest program manager, told the city council in May that there's a 15% two-year tree mortality rate citywide, meaning that about least one out every 10 new trees planted in the city dies. The mortality rate is often a bit higher on the west side.

Tree die-off typically happens when there is insufficient or ineffective watering, either from residents who don't water them or there is a lack of rainfall from drought, Norris explains.

If anything, our harshening local climate strengthens the argument in favor of increased investments in urban forest growth.

–Nick Norris, Salt Lake City's planning director

Salt Lake City's deficit since January 2020 is now over 10.8 inches of water over the span of the past 2½ years, according to National Weather Service data. The deficit is almost twice the amount of precipitation Salt Lake City has received so far this calendar year, and about the same as the total collection from either of the past two water years.

This is why the die-off rate from trees planted since 2020, including Salt Lake City Mayor Erin Mendenhall's plan to plant 1,000 trees on the west side every year, is expected to be higher than 15%. The official numbers aren't expected until later this year, though.

"As the city increases tree planting — beyond for residents who expressly request a new tree — tree planting mortality predictably will increase," Norris explained, in an email with KSL.com. "The City's Urban Forestry Division is focused on increasing new tree survival through increased public outreach and education."

The urban forest also received a beating in September 2020, when a windstorm uprooted or damaged over 3,000 city trees.

Despite these constraints, city planners argue that these events are exactly why more trees are needed in Salt Lake City. They contend that not only will trees benefit what experts outline but that they can also help reduce the water needs of other vegetation and allow for turf to be replaced by mulch, which can reduce outdoor water use.

"If anything, our harshening local climate strengthens the argument in favor of increased investments in urban forest growth," Norris adds. "Trees are remarkably efficient water users and the return on our tree watering investments (is) well worth it."

The next steps

Once the action plan is handled by the city's planning commission, it will be sent to the city council for final adoption. Lindquist said she hopes that it's ready for implementation either by the end of the year or early 2023.

While members of the council had questions about how the plan may be implemented, they seemed optimistic about it on Tuesday. That includes Salt Lake City Councilman Alejandro Puy, who represents a portion of the city's west side.

"I want to see more trees in my district on the west side for sure," he said. "It's one of my goals that those trees do survive — they're not only planted but they make it through the first couple of years."