Estimated read time: 4-5 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

In 2003, Sheana Nelson decided to go on a mission for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Her destination was Mongolia, so the then-Washington State resident traveled to the Missionary Training Center in Provo, Utah to learn Mongolian before she departed for central Asia.

She saw University of Utah Health cardiologist John Ryan, M.D. A nurse on Ryan's team listened to her heart and Sheana learned she had, she says, "a really good example of a heart murmur." Ryan let her hear it.

"The best way to describe it is like a baby on ultrasound," she recalls. "My heart had more of a whooshing sound to it than a normal, solid thud-thud."

Heart murmurs are deceptive issues in cardiology. Sometimes they're nothing to worry about. "If you do an ultrasound and find that there is no problem with heart valves or no obstruction, that's called 'an innocent murmur,'" Ryan explains. "It does not cause damage, but it's worth knowing."

Other times, murmurs can signal serious cardiac problems—even life-threatening ones like Sheana's. But how to tell the difference?

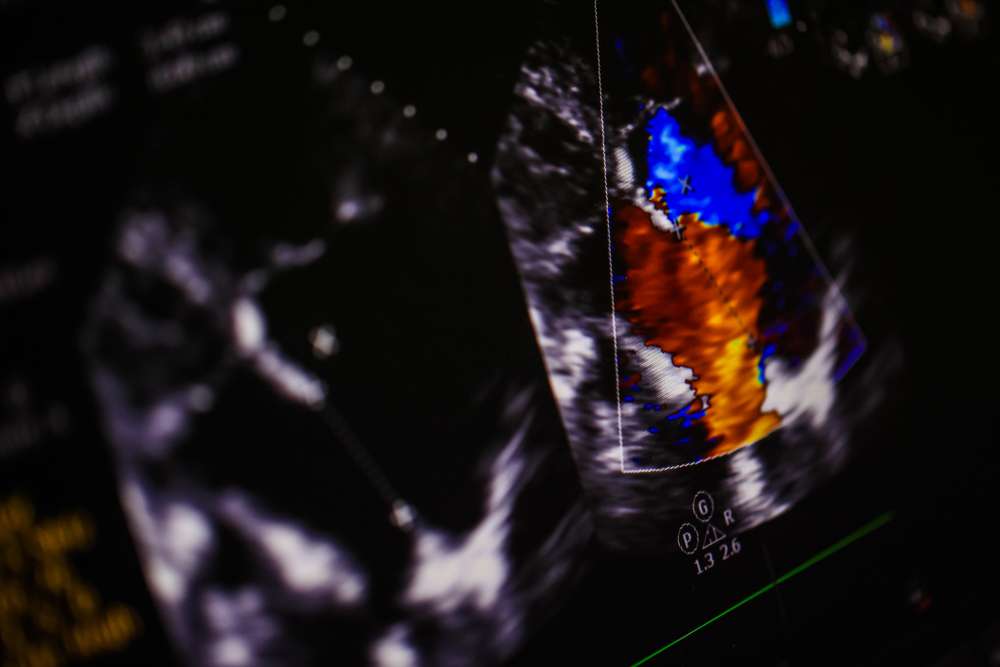

The answer often lies in whether the murmur—what Ryan calls "turbulent blood flow within the heart"—is new or not. Sometimes it's the result of an uneven amount of blood going backwards, called regurgitation. Sometimes it's due to the narrowing of a valve. In some cases, patients are born with a heart murmur or develop it at a young age. But others go through many physicals and primary care visits until, out of the blue, a provider notes that she hears a heart murmur during a routine check-up.

Underlying damage is a concern if heart valve problems exist. Symptoms can include shortness of breath or starting to retain fluid. A leaky or narrowed valve—examples of valvular disease—or a heart beating so quickly it impedes blood flow can all require surgery. "If valvular heart disease causes heart failure, the treatment is to replace or repair the valve," Ryan says. And that can mean open-heart surgery.

The good news in all of this is that despite the potential variety of diagnoses, determining a murmur's innocence isn't an invasive or traumatic experience. Echocardiograms "are so straightforward," Ryan says. "There's no radiation, no stress, and no trauma. No damage can come from it."

In Sheana's case, she needed her deteriorating pig valve replaced. The question was whether it would be a mechanical valve, which would last her the rest of her life, or another pig valve, which she preferred.

She wanted to at least decide for herself. "My life was feeling out of control as it was," she says.

When it came time for the surgery, in August 2016, she changed her mind. She had done a lot of praying, she recalls, and realized that she didn't want her children to have to go through the experience of worrying about her again if a second pig valve needed to be replaced. While she had been quite vocal about preferring a pig valve, she told U of U Health professor of surgery and chief of the division of cardiothoracic surgery, Craig Selzman, M.D., shortly before he operated on her, that she wanted a mechanical valve.

It was a decision that had been made easier, she says, by Selzman explaining to her the advantages of having the mechanical valve.

Four years on from the operation, Sheana is doing well. At night time, when she and her husband go to sleep, in the quiet they can hear her heart ticking, courtesy of the mechanical valve. She has a sound machine to block it out, but that doesn't mean they don't appreciate the medical marvel in her chest. The ticking, "reminds him I'm alive and I feel the same way," Sheana says. "I have gratitude when I hear it. Because of that sound, I'm alive and that's such a gift."