- Whether or not to be vaccinated against measles is becoming relevant as case numbers rise nationwide.

- Utah health officials reported another case Wednesday, bringing the total to 10, all involving unvaccinated individuals.

- Experts advise hesitant families to consult their doctors and consider vaccination for themselves or their children, among other recommendations.

SALT LAKE CITY — Pediatrician Dr. Ryan Gottfredson talks daily with parents about vaccines and most of his young patients at Utah Valley Pediatrics are fully vaccinated. But he's not surprised to see measles cases increasing here and across the country because "a growing number of families are hesitant."

Some parents have their children vaccinated after discussing their concerns. Others — a small but real percentage of families overall — see "more harms than benefits for completing vaccines on the (measles-mumps rubella) schedule," said Gottfredson, who has a masters of public health degree and completed medical residencies in both pediatrics and preventive health.

The question of whether to be vaccinated is extremely relevant as measles case counts nationwide are high and cases have been confirmed in more than 40 states or jurisdictions, despite the fact that measles is not supposed to be a major concern in the U.S. anymore. It was considered eliminated about 25 years ago, a status that could be in jeopardy given the number of recent outbreaks and cases.

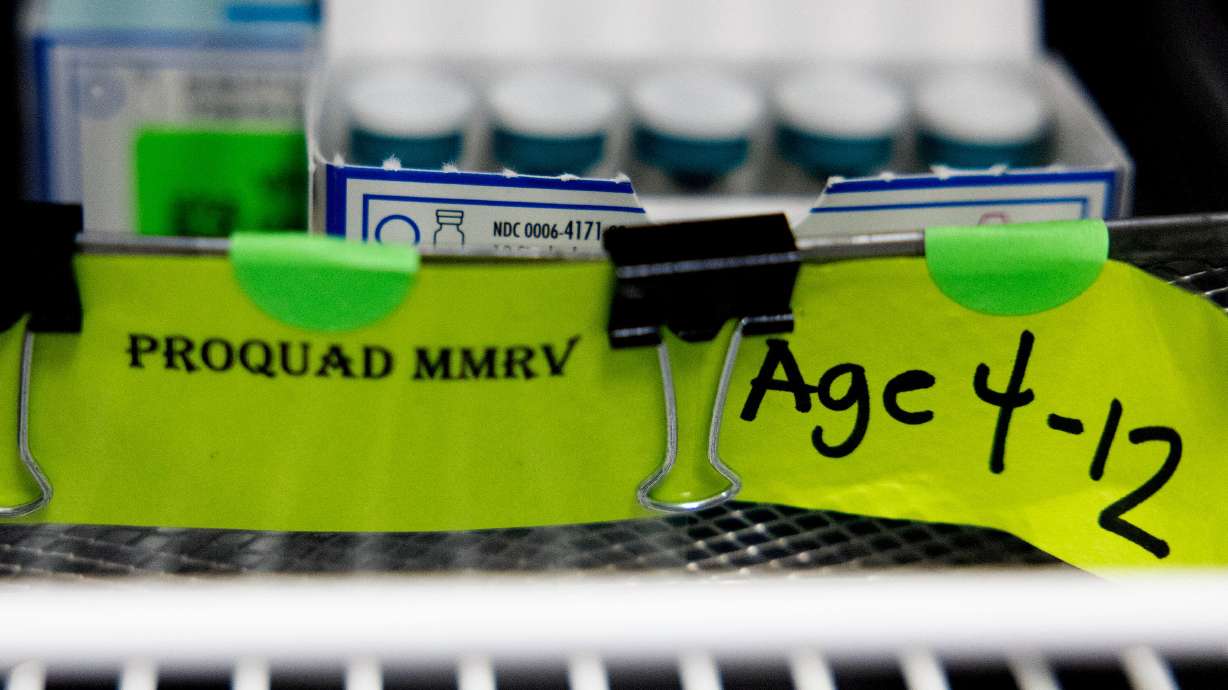

The Utah Department of Health and Human Services on Wednesday confirmed a new case, bringing the state's total to 10 so far in 2025. Cases have been confirmed in the Utah County and Southwest Utah health districts.

Nationally, there were 1,309 lab-confirmed cases as of Tuesday, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which said there are also suspected cases.

There have been 29 outbreaks — three or more related cases — nationally this year and 92% of the confirmed cases involve individuals who were unvaccinated or whose vaccine status is not known. All of Utah's cases, which include nine adults and one minor, involve people who have not been vaccinated, public health officials said.

Which raises a question: If some people really don't trust and will not get vaccinated, are there steps families can take to reduce the risk of transmission of this highly contagious illness?

Information, misinformation and uncertainty

Dr. Syra Madad believes wholeheartedly that vaccination is the best protection from measles, which is always miserable and can be deadly. Madad, the chief biopreparedness officer at NYC Health + Hospitals, told Deseret News that two doses of the mumps, measles, rubella vaccine provides 97% protection against the virus, which is so contagious that someone who has measles will infect up to 90% of those they come in contact with if they are not vaccinated or immune because they already had measles.

Gottfredson agrees that the MMR vaccine is a vital form of protection. He is equally convinced that parents, regardless of their views on vaccination, are dedicated to doing what they believe is best for their families and are making their decisions with love.

"They want to do the right thing," he said. "They're just concerned that maybe we've got this one wrong, maybe something about vaccines is going to cause harm to their children."

Questions on whether the pandemic was handled correctly have spilled over to other things, he said, including medical advice. "Emphatically yes, there's a massive uptick in distrust," Gottfredson said.

He added, "We see a strong correlation with COVID and particularly a lot of distrust regarding the COVID vaccine and that's unfortunate. It's a challenge I think we're still trying to figure out how best to address."

His solution is relationship building and sharing the decades of research that show the safety and effectiveness of the vaccine, he said. But it's still not easy with those described as vaccine hesitant.

"I've had parents in tears, conflicted with the decision. They don't want to harm their child by giving them the vaccine," Gottfredson said. "But they don't want to harm their child by letting them get a vaccine-preventable illness. Some people are in turmoil about that and I am sympathetic to that."

People are inundated with often contradictory information, he noted. Information they get from sources like social media or influencers may not match scientific arguments.

He's certain that vaccines are more than valuable; they're the best way to prevent measles spread and infection. But he tells colleagues to be kind and check any impatience they feel with those who disagree or question.

Advice for the vaccine-averse

The number of people seeking exemptions from having children vaccinated to attend school has climbed, as Deseret News recently reported. The number of children arriving at kindergarten fully vaccinated has dropped.

So Deseret News asked Gottfredson and others what parents who don't get their children vaccinated — or parents whose children cannot be vaccinated because they're too young or have medical conditions that preclude the measles vaccine — should do.

Gottfredson said that while he is sympathetic to the uncertainty many people feel, it reminds him of being told by a mechanic that your car needs an unwelcome $2,000 transmission repair. It might make sense to get a second opinion. But if you do that 10 times or 100 times and all the mechanics say the same thing, you probably do need a new transmission.

Among health experts, he sees little variation in what doctors and researchers recommend to prevent measles. "Most pediatricians, most vaccine researchers are on the same page." He said most parents come around, too.

But not all of them. That doesn't mean they want their children to get measles.

Deseret News asked Utah's public health officials in the Department of Health and Human Services for advice for those who will never get a vaccine but want to avoid measles. The response:

- Surround yourself with other vaccinated persons, especially in your household, if possible.

- If you're exposed to someone who has the measles, talk to a doctor about post-exposure vaccination or medication.

- Avoid large gatherings and crowded places in areas with known outbreaks and ongoing transmission.

- Consider getting the MMR vaccine at least one month before trying to get pregnant, to avoid harm to your baby during pregnancy.

- Stay away from others if they are sick.

For anyone who thinks they or their child could have measles, those health officials recommend:

- Stay home and away from others as much as possible.

- Seek care if you have a hard time breathing or if a fever won't come down.

- Call the clinic or provider ahead of time and let them know you are concerned about measles to protect other people from getting exposed in the waiting area, such as pregnant women and babies.

The best the parent of an unvaccinated child can do "is try to minimize their exposure," Madad said. "This includes avoiding crowded indoor settings especially during outbreaks, keeping them away from individuals who may have been exposed as well as those with symptoms such as fever, cough and rash and monitoring local public health alerts."

She continued, "However, even with these measures, the risk remains high. We do not live in isolation and children can be exposed in everyday environments like schools, airplanes and grocery stores. If you have questions or concerns about vaccination, I urge you to speak with your health care provider."

Gottfredson said that while it's impossible to live in a bubble, herd immunity can help. That refers to being surrounded by enough people (mid-90%) who've been vaccinated or have natural immunity because of previous infection that a protective barrier hampers spread. He added that a small percentage of people who were vaccinated also never made antibodies so they're still susceptible to measles.

The only sure way for someone without immunity who won't get vaccinated to avoid measles is to only be around people who are immune, he said. If the virus travels through a community that's not vaccinated or naturally protected, the chance of stopping it is low.

Masking with a really good mask can help, but the "average Joe who buys an N95 mask off Amazon will not necessarily be protected from measles," Gottfredson said.

A risky illness

There are few things as well-studied as the MMR vaccine, per Gottfredson. "It's been around for decades and decades. At this point, we have so much information and so many studies published about its safety."

But he surprises parents by acknowledging that the possibility of a vaccine injury exists. "That can happen; it's just that it's really rare." Vaccine can trigger an allergic reaction or other complication. One worried-about risk is Guillain-Barré syndrome, in which the immune system mistakenly attacks peripheral nerves, causing muscle weakness and sometimes paralysis. The National Institutes of Health reported that the likelihood a measles vaccine could launch the rare syndrome is "not statistically significant." The risk is actually greater from having measles.

Measles carries real risks. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that 1 in 4 or 5 children who contract measles will need to be hospitalized. Between 1 and 3 of every 1,000 individuals with measles die from respiratory and neurologic complications. One in 1,000 develop acute encephalitis, in which the virus infects brain tissue. "If you survive that, it's often the case that you're not neurologically the same ever," said Gottfredson.

The CDC said encephalitis from measles may cause intellectual disability or deafness. More common complications include pneumonia and ear infections. Years after infection, 1 in 10,000 who had measles develop subacute sclerosing panencephalitis, a rare but lethal degenerative neurological condition that leads to memory loss and seizures, then inevitably death. "You cannot stop it," Gottfredson said.

When the community rate of vaccine uptake drops, a measles outbreak occurs, said Gottfredson, who notes a worldwide pattern. When the community gets vaccinated again, measles goes away.

His advice to families? Talk to your health care provider. But he admits that inadequate access to primary care is a real problem for many people. That makes it harder to ask questions or have a constructive discussion, he said.

As for health care providers, Gottfredson said, "Be patient and empathetic with families. They love their children and want to do their best for them."