Estimated read time: 8-9 minutes

- Utah faces a surge in fentanyl and meth, prompting policy overhauls.

- Overdose deaths rose 5% in 2024, contrasting a national 24% decrease.

- New laws aim to curb drug distribution and enhance treatment resources statewide.

SALT LAKE CITY — Utah is in the middle of overhauling its approach to drugs and homelessness.

At the root of this makeover is one deadly fact: The state has been flooded with a new generation of narcotics that an old set of policies are inadequate to confront.

An unprecedentedly large and lethal influx of fentanyl pills and "super meth" has forced state officials, not just in Utah but around the country, to completely rethink their approach to preventing, treating and prosecuting the evolving overdose epidemic.

"It's changing almost everything we've ever thought about drugs," author Sam Quinones told the Deseret News. "What we need to understand is that this is a new era."

This is the message Quinones, the award-winning author of "The Least of Us: True Tales of America and Hope in the Time of Fentanyl and Meth," plans to bring to Salt Lake City on May 7 during a Solutions Utah conference with Utah Gov. Spencer Cox.

The visit could hardly come at a better time as Utah finds itself as an outlier in terms of drug overdose deaths with drug seizures of fentanyl and meth continuing to grow.

Utah's growing fentanyl problem

In 2024, Utah was one of only five states that saw a jump in overdose deaths, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. While the country as a whole had a 24% decrease in overdoses from 2023 to 2024, Utah had a 5% increase.

This comes after Utah recorded its highest number of overdose deaths ever in 2023. That year there were 606 drug overdose deaths in Utah, with 290 of those involving fentanyl, according to reports from the Utah Department of Health and Human Services.

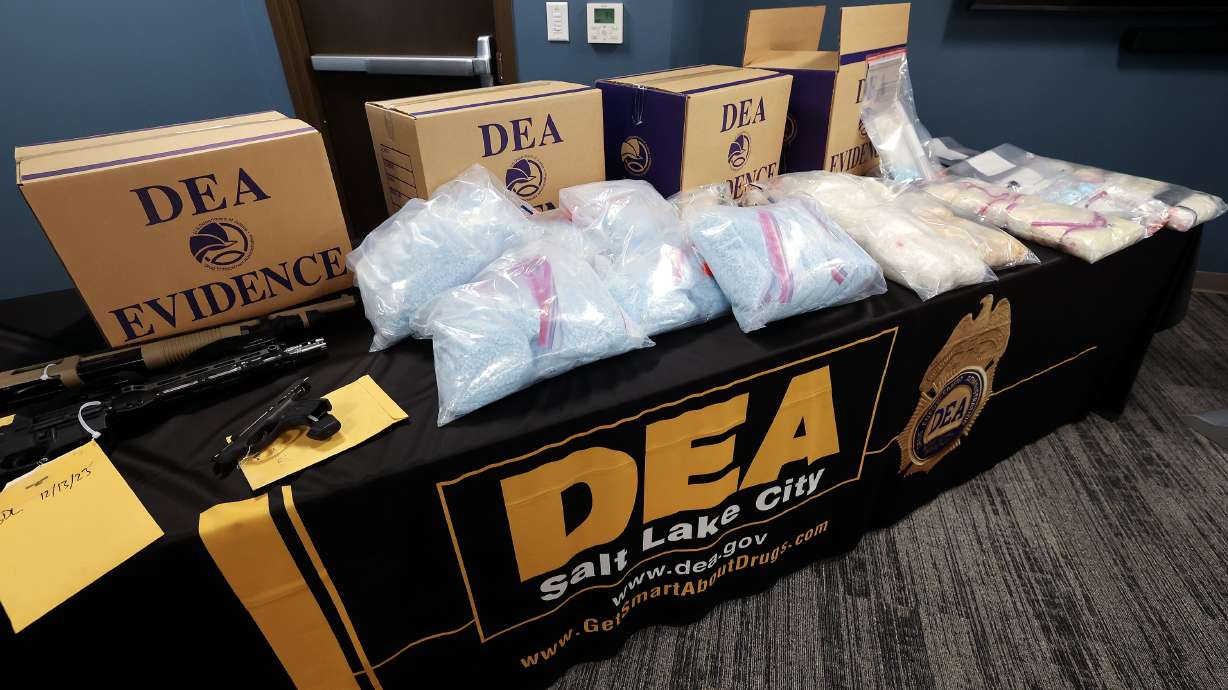

Along with this tragic record, Utah law enforcement is seeing significantly more fentanyl enter the state and stay here.

In 2020, Utah task forces of the Rocky Mountain High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area seized over 49,000 dosage units of fentanyl. That increased sevenfold to 330,000 in 2021 before quadrupling to 1.5 million in 2022, doubling to 3.4 million in 2023 and hitting 4.7 million in 2024 — totaling 95 times the amount of interdicted fentanyl from four years earlier.

The pace isn't slowing down. Utah Highway Patrol and the State Bureau of Investigation have already seized nearly as many dosage units of fentanyl in the first four months of 2025 as they did in the entire year of 2024.

But potentially the most worrying statistic is that, unlike in past years, around half of those drugs were destined for Utah markets instead of just passing through the state, according to Utah Department of Public Safety Commissioner Jess Anderson.

"That causes me great alarm," Anderson said. "Either we've got a demand issue going on here in Utah that we were not aware of ... or we've got more of ... a cartel issue ... than what we would like to admit."

A death sentence for the homeless

No one has been harder hit than those living on Utah's streets.

In 2023, the No. 1 cause of death for people experiencing homelessness in Utah was drug overdose, accounting for 35% of the 216 homeless deaths recorded that year, compared to 5% of deaths in the general population.

The fatality rate associated with fentanyl — which is 50 times stronger than heroin — has flipped the consensus approach to homelessness on its head, according to Quinones.

No longer can localities justify permanent encampments or "housing first" programs that offer low-barrier apartment units or shelter space with no requirements for sobriety or treatment, Quinones said, because doing so is a death sentence.

"The problem is now, if you leave people on the street to find readiness to hit rock bottom, meth will drive them mad, and fentanyl will kill them before any readiness for treatment ever takes place," Quinones said.

After spending more than 10 years reporting in the towns most impacted by drugs, Quinones has concluded that what places like Utah need to do is develop replacements for the approaches refined in a pre-fentanyl America.

One solution Quinones has seen take hold in some counties is to use jail time for arrested individuals as a forced detox period to encourage recovery and treatment upon release.

Recalling one individual who was arrested with 94 warrants against him, Anderson agreed that law enforcement needs additional resources "to break the cycle" by helping people get sober "in a humane way," potentially with a 30-day jail stay, to decrease the chances that arrested individuals exit and immediately look for ways to get more drugs.

Utah Rep. Tyler Clancy, R-Provo, who has spearheaded recent efforts to transform the state's goals on homelessness, is also on board. Many fentanyl addicts use the drug eight to 10 times every day, said Clancy, who is a detective with the Provo Police Department.

"We're fundamentally misunderstanding the depth of this addiction and misunderstanding the danger of fentanyl," Clancy said. "When someone's in the absolute thick of addiction, it's mandatory treatment or death or destroying their life or leaving citizens on the streets of our cities to be subject to disorder and crime."

New law enforcement initiatives

During the last legislative session, Clancy sponsored HB199, which would allow first responders to connect overdose survivors to treatment resources while prohibiting syringe exchange programs in certain areas, and HB329, which would require shelters to maintain a zero-drug policy while enhancing criminal penalties for drug distribution in the surrounding areas.

Both bills passed the Legislature unanimously and will take effect on May 7. They were accompanied by HB87, sponsored by Rep. Matthew Gwynn, R-Farr West, which would make the trafficking of 100 grams or more of fentanyl a first-degree felony. The bill also became law with a unanimous vote in both chambers.

"If you're caught with fentanyl, 100 grams or more, we will treat you as if you are coming to our communities trying to kill our people," Anderson said. "That is what happens with overdoses, and so therefore we will hold you accountable."

During the first two months of 2025 before HB87 was passed, Utah law enforcement encountered 47 individuals in the Salt Lake City area who would have qualified for the new felony designation, Anderson said.

In response to Utah's growing number of overdoses, Cox tapped Anderson in October to head the new Utah Fentanyl Task Force, which has the goal of reducing drug overdoses by 25% before 2029.

The initiative hopes to rebuild Utah's approach from the ground up with groups focused on improving the state's drug data, revamping long-term recovery programs, conducting public outreach about the dangers of fentanyl and increasing police presence.

There are already signs that this renewed focus is bearing fruit, according to Anderson. With more officers to disrupt key drug distribution areas, the price of fentanyl has increased from $1 per pill to $10 per pill, Anderson said.

Anderson's office believes this contributed to what they expect to be a 3% decrease in overdose deaths during the final quarter of 2024, which was not included in the CDC survey.

But as fentanyl faces pressure from law enforcement "it's actually being overtaken by meth," Anderson said. "Word about fentanyl is actually getting out."

Community-driven solutions

To avoid playing whack-a-mole with new drug variants, the state needs to increase efforts to address the root of drug supply as well as drug demand, according to Anderson.

A newly secured border under the Trump administration is expected to help cut off some trafficking, Anderson said, pointing out that "half of those that we pick up dealing the drugs are illegal immigrants."

But local solutions must focus just as much on demand as they do on supply, Quinones found while researching his book in towns like Portsmouth, Ohio.

"Frequently towns need municipal recovery as much or more than they need drug addiction recovery," Quinones said.

This kind of recovery comes in unlikely forms. One of Quinones' favorite solutions is community swimming pools, which he said are a perfect example of the kind of public space that bring people together and encourage healthy habits.

In addition to investing in public recreation, Quinones said counties have experimented successfully with setting aside areas of jails as rehab pods, where inmates can successfully detox to reduce recidivism.

But jails and prisons are far from the best place to treat the problem of drug use, according to Amanda Alkema, the behavioral health director at the Utah Division of Correctional Health Services, which oversees the medical care of the state's roughly 6,500 prison inmates.

"When there is illicit drug use going on in the prison, it's not always also the right place to try to detox somebody," Alkema said. "A prison's never going to really provide a therapeutic environment."

More funding could help move the state toward Quinones' vision of designated detox areas, Alkema said. About two-thirds of prison inmates have substance use disorders, including around 1,500 who have opiate use disorder, according to Alkema.

To be effective, these funds would need to help provide comprehensive care, Alkema said. Currently there is only one mental health medication prescriber for every 170 patients with serious mental illness in Utah prisons.

However, more funding and forced detox can only accomplish so much, according to Clancy. Ultimately, America and Utah's drug and homelessness problem finds its source much closer to home.

"The No. 1 cause of homelessness is a catastrophic loss of family," Clancy said, quoting Alan Graham, founder of the Community First! homeless village in Austin. "That is a huge thing we're seeing, not just with our neighbors who are homeless, but across the country, we're becoming more and more disconnected from one another."

After all, Clancy said, the opposite of addiction — which seeks isolation and shuns accountability — is community, and if there's anything Utahns can rally behind it's that.