Estimated read time: 3-4 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

PROVO — Can the brain fool itself into ignoring signals for chronic pain?

If it can, Brigham Young University researchers want to know if they can observe or measure actual changes in the brain after a patient has had a new kind of pain therapy, the kind Jennifer McLean is now experiencing.

"It's just kind of unbelievable dealing with it for so long and then not having the pain there. It's really nice," she said while holding back tears. McLean feels something she's not had for a long time — relief.

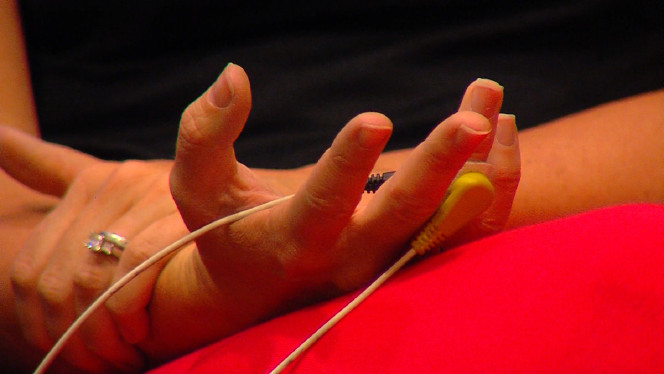

The 24/7 excruciating, stabbing, pulsating neuropathy in her right hand and fingers is gradually diminishing because a new generation electrical stimulation device is sending another signal to her brain. For more than a year, the young mother from California had gone from 21 pain drugs down to 15 before starting the therapy. Now it appears she may be close to stopping medications altogether.

McLean said, "It's been such a blessing to have some relief and to know there is finally a light at the end of the tunnel."

She's not alone.

Taylor Johnson, who couldn't walk because of chronic pain in his legs that had no known source, is now pain free.

So are Brock Roblin and many others from Utah and around the country. After 12 or so treatments on a device called Calmare, the brain appears to no longer recognize errant pain signals coming from neuropathy or from an injury that has long since healed.

KSL-TV

Dr. David Busath, who is heading up the research at BYU, said, "I think the fooling the brain idea is a legitimate one, if it turns out that way that we're convincing the brain in one area that this other area shouldn't be hyperactive after all."

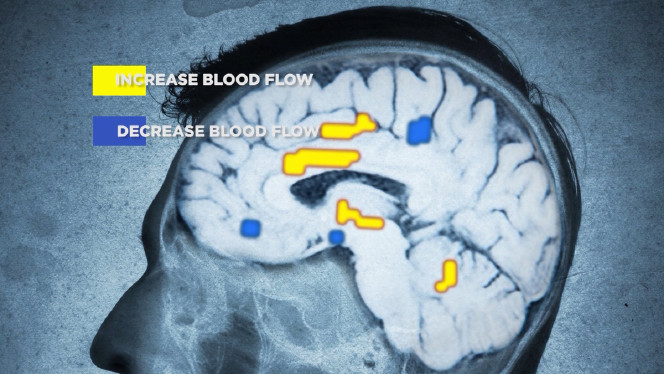

Along with clinical trials at Johns Hopkins, the Mayo Clinic and other universities, BYU researchers hope to observe via MRI scans what is actually happening inside the brain.

According to Busath, "We will take an MRI for 20 minutes, treat for 30 minutes and then take another MRI for 20 minutes."

From previous studies, other scientists know pain signals both increase and decrease blood flow in the brain.

But something else is going on.

One theory suggests that Calmare is sending controlled electrical stimulation along another branch of nerve fibers, called the "C" fibers, and that may be why patients experience more lasting relief. While immediate injury pain transmits along other faster nerve pathways, the slower "C" fibers may be transmitting exaggerated long-term signals that the brain legitimately could ignore.

According to pain therapist Erick Bingham, "Patients may go from an eight or nine or 10 level of pain down to zero, and some of these people haven't experienced that in years."

KSL-TV

Bingham said some need a periodic booster while others remain pain-free with no need for future treatments. A lot depends on how the patient reacts after the very first therapy. Bingham believes their response at that time is a predictor of the outcome. "I would say 80 percent of the time, if they get a good response on that first treatment, they're going to b e a good candidate."

McLean hopes that's her story.

"I'm ready to have my normal life back," she said.

And with research now and more studies down the road, scientists hope to understand how that happens.

For those wishing to participate in the study, they can contact Busath at 801-422-8753.

To be eligible for participation, volunteers must have constant sharp pain in the hands or feet and not be on any anticonvulsant medication. They must also have no stents, pacemakers or other implants that would interfere with an MRI scan.