Estimated read time: 7-8 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

GREEN RIVER, Emery County — Utah's great waterways, the Green River and the Colorado, were shrouded in mystery for most of the 1800s. Their towering cliffs, deep canyons and wild whitewater kept most people out.

The famed one-armed Civil War veteran John Wesley Powell is generally remembered as the first white man to conquer those rivers in 1869.

But there are least two earlier travelers who might be entitled to some of that glory, and there's also an unsolved mystery: What happened to three members of Powell's crew, whose fate was swallowed up by the forbidding landscape of the Grand Canyon?

These are three enduring legends of the Green and the Colorado.

1836: The Mountain Man

A modern-day traveler can descend into the depths of Labyrinth Canyon on the Green River southwest of Moab and find what may be the coolest bit of graffiti in Utah.

A well-maintained road drops off the edge of an enormous mesa called Island in the Sky near a popular camping spot named Mineral Bottom. From there a rough Jeep road heads upriver to a place called Hell Roaring Canyon. A long time ago, someone hiked a few hundred yards away from the Green River and into the side-canyon to leave his mark on a canyon wall.

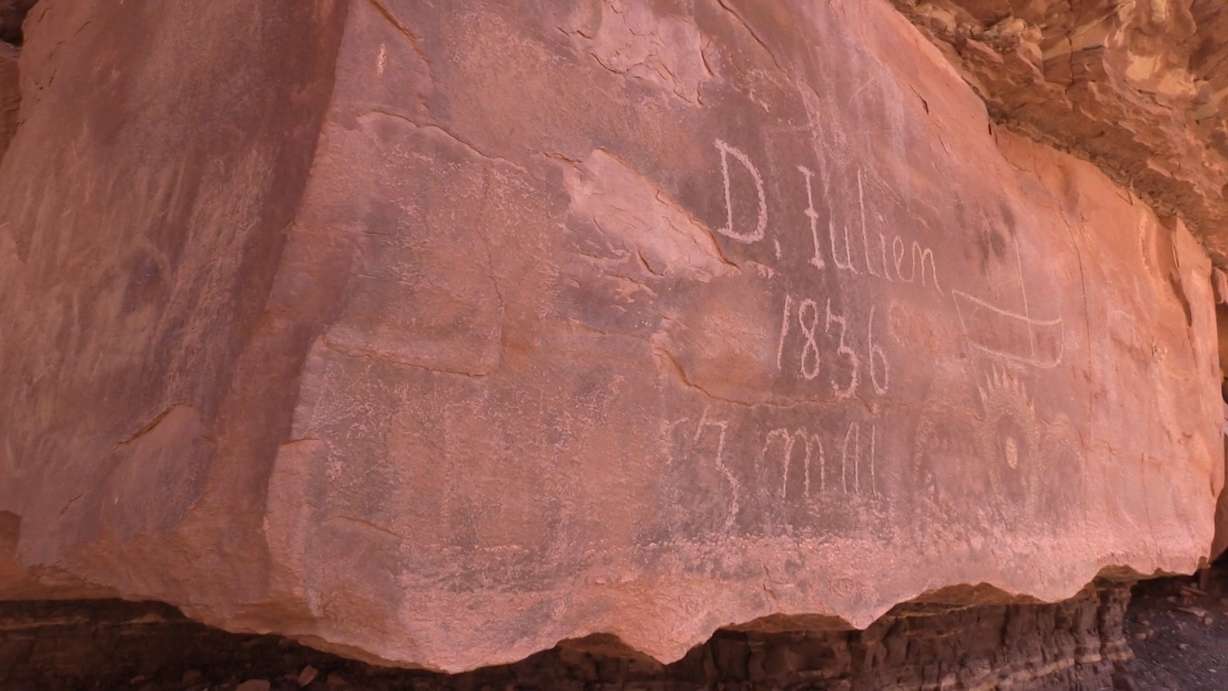

His graffiti is now on the National Register of Historic Places, an inscription from a mysterious visitor that reads in its entirety, "D Julien, 1836, 3 Mai."

The date, written in French, is a giveaway to Julien's identity.

"Really he's kind of a mystery," said Tim Glenn, director of the John Wesley Powell River History Museum in Green River. "We don't know a whole lot about him."

What is known is that he was a French-American fur trapper — a mountain man — named Denis Julien who spent years traveling through the West in the 1830s and 1840s. His name turns up in old documents surrounding the fur trade business in St. Louis.

"He left his name carved in stone up and down the Green and the Colorado river systems," said Western history aficionado Ken Sanders of Ken Sanders Rare Books. "Sure, he was there, but we don't know anything about him."

In recent years scholars have tracked down information suggesting that Julien worked in the fur trade for several years in the Midwest, specifically Iowa and Wisconsin, before heading to the Mountain West. Some writers have speculated that he later moved on to California and died in obscurity.

The 1836 inscription is Julien's most famous. Life-size replicas of the carving have hung for years in the river history museum in Green River and in a BLM office in Moab. Three other Julien inscriptions are on the National Register of Historic Places, and several more are considered authentic. His first inscription in what is now Utah is dated 1831.

One of the controversies about Julien is whether he traveled long distances by boat on the Green and Colorado rivers instead of just crossing them periodically, and whether he might have even traveled upstream — against the current — on the notably wild rivers.

The dates of his inscriptions are a clue.

Many miles downriver from Hell Roaring Canyon, another Julien inscription from 1836 was found below the confluence of the Green and Colorado rivers. It was apparently carved by Julien on a rock wall below some of the biggest rapids in Cataract Canyon. It read simply "1836 D Julien" without specifying the month or day. But a third inscription from 1836 was found upstream from Hell Roaring Canyon at a place called Bowknot Bend. It reads "D Julien 16 Mai 1836," a date just 13 days later than the inscription in Hell Roaring Canyon. That suggests Julien traveled upstream, at least during those 13 days.

Another clue is a crude sketch of a boat that's part of the Hell Roaring Canyon inscription. Julien's depiction of the boat seems to include a sailing mast. To some, that suggests he sailed up the rivers by taking advantage of winds that frequently blow against the current.

"We know he was using a sail," Glenn said. "And if there are rapids, you can always portage around them. So it's absolutely possible somebody could go up river, even back then."

That bit of speculation is a bit too much for some to swallow.

"Sailing upstream?" Sanders said. "Ahhhh! I'm not a good enough sailor to pull that off."

1867: The accidental tourist

The controversy about Julien is mild compared to the Grand Canyon legend of James White. His story has been told and retold for 150 years, and no one knows how much of it to believe.

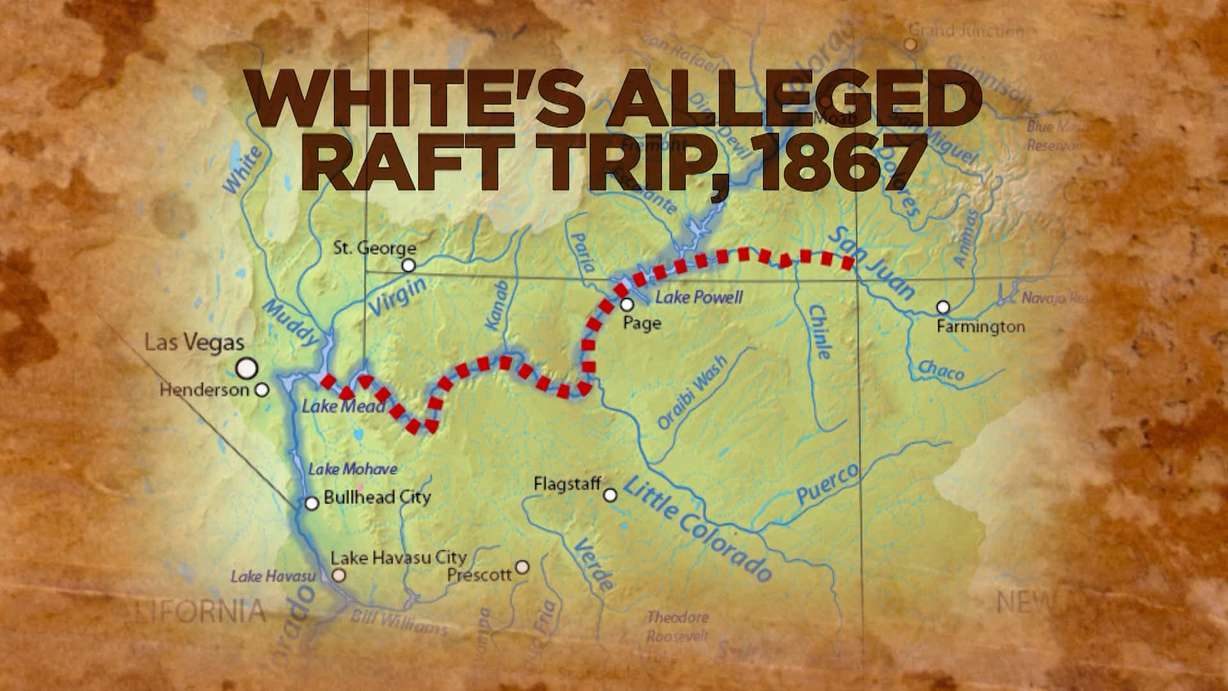

One day in 1867, a worn-out, sunburned, water-logged prospector came floating out of the Grand Canyon on a raft made with logs. It was James White and he babbled an astounding tale. He claims he and some colleagues were attacked by Indians in the San Juan Mountains of Colorado. White and another man jumped in a river and floated downstream on a crude log raft. The companion died and White floated on, traveling for a total of 14 days through what is now Utah, Arizona and into Nevada.

If his geographical account was correct, White must have traveled down the San Juan River to the Colorado River, through Glen Canyon and Marble Canyon, and finally through the Grand Canyon itself with its many mighty and death-defying rapids.

"I don't see how he could have," said Sanders. "I don't think the raft would have stayed together that long."

Yes, the story seems wildly improbable. Even those who have no reason to suspect White made up the story wonder if he was simply confused about the geography.

But some are not so quick to dismiss White's tale.

"It's certainly pretty fantastical," Glenn said. "But he knew things about the (Grand) Canyon that you wouldn't know unless you had gone down it."

Related story:

"He wrote enough that it seemed plausible, yes," said veteran river guide Ken Sleight. He was once approached by White's granddaughter to see if he could use his knowledge of the Colorado River to verify some of White's geographic details.

"White left out a lot of stuff and some of it's not right," Sleight said, "but that doesn't make it that he didn't do it, in my mind."

1869: Three who vanished

And then there's a legendary aspect — a mystery, really — of Powell's famous expedition two years after James White. Powell's prickly personality may have contributed to a disastrous episode.

"I don't think Powell was that easy to get along with," Sleight said. "Pretty demanding."

Powell and his crew of nine began the historic expedition by launching their boats at what is now Green River, Wyoming, on May 24, 1869. They traveled hundreds of miles down the canyons of the Green River to its confluence with the Colorado River and battled their way through the treacherous rapids of Cataract Canyon.

By late August they were in the depths of the Grand Canyon, where the whitewater is even more extreme. For three members of the expedition, facing yet another frightening plunge into wild rapids, it was just too much.

"They didn't know what was around the next bend," Sanders said. "They had to have been terrified, out of their lives."

On Aug. 28, 1869, the three decided to bail out — climb out — of the Grand Canyon. Powell gave a share of the expedition's supplies to Bill Dunn, Oramel Howland and his brother, Seneca Howland.

"There were tensions," Sanders said. "The three of them, I think they parted with regret and remorse, but no bad blood between them."

The three men abandoned the river expedition at a place that is still called Separation Rapids. They hiked away and were never heard from again.

For a century-and-a-half, various theories have been debated. Most historians believe they were killed by Indians; a chief supposedly admitted the killings to Powell himself. Others have speculated they were killed by a conspiracy of Mormons in southern Utah.

The truth? Well, here's one thing on which most historians agree:

"We'll never know, probably," Sanders said. Echoing the thought, Glenn said, "I don't think we ever really will know."

Perhaps it's no surprise that a landscape so resistant to people getting in — or getting out — would keep some of its mysteries forever.