Estimated read time: 7-8 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

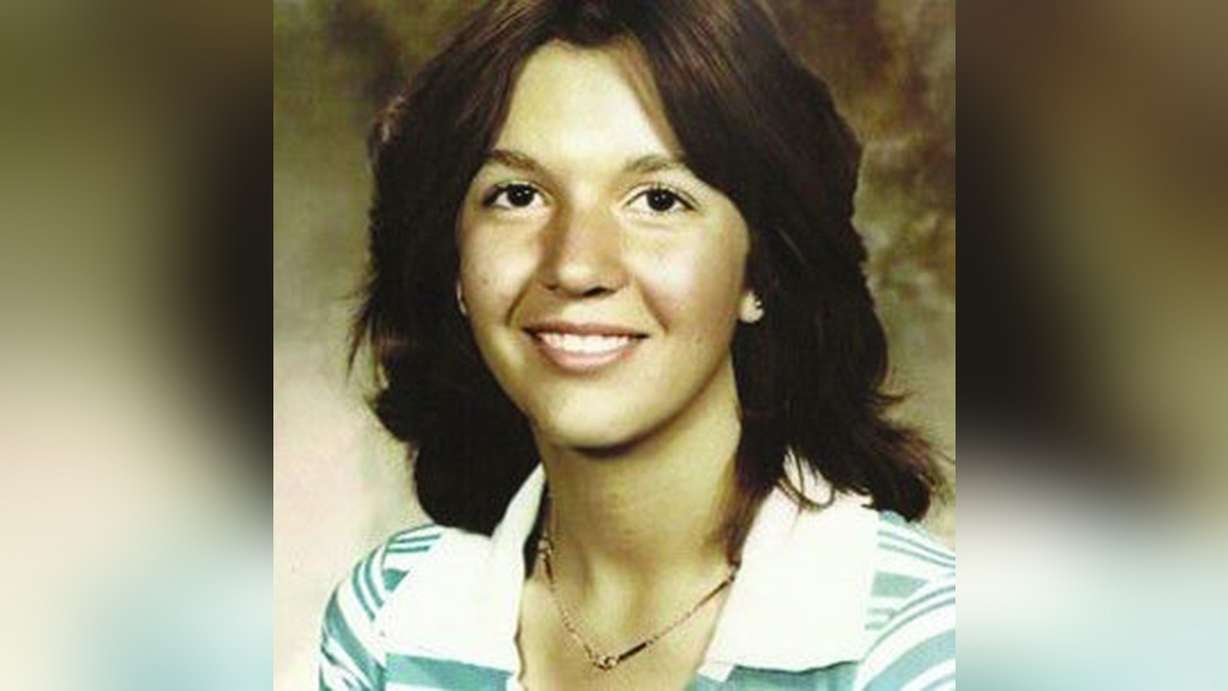

POCATELLO, Idaho — Ted Bundy, one of the nation’s most notorious serial killers, abducted 12-year-old Pocatellan Lynette Culver on her way home from Alameda Junior High School and killed her over four decades ago, throwing her body into the Snake River.

At least that’s what authorities have said ever since Bundy confessed to her murder in 1989 and revealed to former Idaho Attorney General Jim Jones personal details about her life that only Culver would know.

But the Pocatello Police Department — the agency that initially investigated her disappearance — is now casting doubt on that theory by suggesting it’s possible someone other than Bundy abducted and killed Culver.

“We don’t have a body and (Culver) is still a missing person,” said Pocatello Police Capt. James McCoy, referring to the fact that Culver’s body was never found. “During the initial investigation, there were multiple individuals who came forward with conflicting information. And until we can find her remains or there is absolutely nothing else we can do, we are going to continue to look into this.”

The investigation into what happened to Culver has not been reopened, as it has never officially been closed, said McCoy, adding that Culver’s case is one of several from the late 1970s and early 1980s involving Pocatello girls who were abducted and killed. Pocatello police recently announced that they are reinvestigating the cases involving the girls as well as other cases that have gone cold in the last 20 years.

The big difference between this and previous reinvestigations of these cold cases is that Pocatello police are looking at all the disappearances and deaths collectively this time around to see if there are commonalities.

Police aren’t ready to say a serial killer might have been behind at least some of the cases but it’s clear that possibility is being examined.

McCoy said, “What they were doing before was looking at one cold case each month or so and getting different perspectives on it but they weren’t reviewing the cases all at once.”

That changed earlier this year, however, when a Pocatello police detective working one of the cold cases swapped folders with another Pocatello police detective, McCoy said. Both detectives noticed a few similarities between the cases, said McCoy, adding that he could not discuss the specifics of any case because the investigations are active and ongoing.

McCoy admitted the Pocatello Police Department doesn’t have any information that indicates whether any of the cold cases are definitively linked. But he said several of the department’s investigative reports regarding the disappearances and deaths of the girls include some of the same names and dates. This is in addition to most of the girls attending the same school — Alameda Junior High — and all being around the same age.

Culver was the first of the five girls to go missing in Pocatello between 1975 and 1983. She was reported missing in May 1975 — three months before Bundy was arrested by a Utah Highway Patrol officer in Granger, a Salt Lake City suburb.

Bundy confessed to abducting Culver in the area of Alameda Junior High and taking her to a Pocatello hotel where he killed her, according to a 1989 article in the Orlando Sentinel.

Bundy told authorities in 1989 that he knew Culver’s family relocated from one side of Pocatello to the other, something Jones corroborated and believed only someone who directly interacted with Culver would know.

It’s worth noting that Bundy was incarcerated when the four other Pocatello girls were abducted and murdered and thus could not have been involved in those cases.

The next disappearance came in July 1978, when two girls who also attended Alameda Junior High went missing from Alameda Park about one mile east of the school.

Tina Anderson, 12, and Patricia Campbell, 15, were reported missing from a Pioneer Day celebration at the park on July 22, 1978. Both girls saw various friends at the park that day. They left family members at the swing set to go buy the group corndogs and never returned.

The girls’ remains were discovered by hunters in the Trail Hollow area in Oneida County in October 1981 and Anderson was identified using dental records shortly thereafter. Though investigators always believed the remains discovered next to Anderson’s belonged to Campbell, DNA testing didn’t confirm her identification until 2007.

On the 40th anniversary of the disappearance of Campbell and Anderson last month, Crystal Douglas of East Idaho Cold Cases Inc., an Idaho Falls-based non-profit group aimed at investigating unsolved crimes and disappearances, sent out a public request via social media seeking information about the events that occurred prior to the girls’ deaths.

Douglas asked for people to come forward who took pictures at Alameda Park the day Campbell and Anderson disappeared or who have any details about the girls — where they went that day, who they were with and/or the things they talked about in the hours leading up to their disappearance.

Linda Smith, 14, a student at Franklin Junior High, disappeared in the early morning hours of June 14, 1981. Police reports at the time said Smith struggled with a stranger in her family’s home on North Eighth Avenue and the confrontation was witnessed by her 9-year-old brother Ben.

The boy also wrestled with the stranger, according to reports, but ran to a neighbor’s home for help after being pushed to the ground.

In May 1982, Linda Smith’s remains were discovered by children playing in a ravine near Hospital Way on Pocatello’s east side.

Another female student at Alameda Junior High, Cindy Bringhurst, 14, was babysitting a 2-year-old child the night of June 4, 1983, on Highland Avenue when she vanished. When the mother of the child returned home about 1:45 a.m. after finishing her work shift at the Oasis Bar, Bringhurst was missing. The 2-year-old was unharmed and there was no sign of a struggle in the apartment.

A fisherman discovered Bringhurst’s remains a month later in the Mink Creek area south of Pocatello.

McCoy said the disappearances and deaths of the girls are unusual because they all happened during an eight-year span.

“This is a significant cluster of dead or missing girls in a relatively short time period,” McCoy said. “Something like that is a huge anomaly for this town.”

McCoy declined to say whether police believe a serial killer is responsible for killing the girls.

McCoy said Pocatello police detectives are utilizing new technologies such as advanced DNA testing and historical satellite imagery in their reinvestigation of the cold cases.

Also part of the reinvestigation are the cold cases involving missing persons Jon Barrett and Kimberly Vialpando, McCoy said.

Jon Barrett disappeared in November 2008. He was 68 years old and a diabetic. He left behind his dogs and his van, which mysteriously showed up at his Pocatello home the day after he was reported missing. Police don’t know who returned the vehicle.

Barrett has never been located and police say his disappearance remains a total mystery.

Kimberly Vialpando was last seen in Pocatello on May 5, 2000. She worked at American General Finance. On May 19, 2000, her pickup truck was located in the 300 block of North Johnson Avenue. The Portneuf River was searched after her disappearance, but nothing was found. Like with Barrett, police say she vanished and they have no idea what happened to her.

Considering the time that has passed with all of these Pocatello cold cases, Douglas said it’s likely that many of the victims’ surviving relatives are running out of faith.

“I think the older these cases get the more resigned some of their family members are and the more reluctant they are to expecting justice sometime in their lifetime,” Douglas said. “It’s hard for them to get their hopes up.”

But Pocatello police said they’re not giving up on any of the cold cases.

“I just want the evidence to lead us where it is going to,” McCoy said. “Our mission is to find the truth and that is all we are after. We aren’t looking at just closing the case. We are looking for a truthful conclusion. Forty years is a long time to wait, but we’re trying to let the families finally close the book.”