Estimated read time: 4-5 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

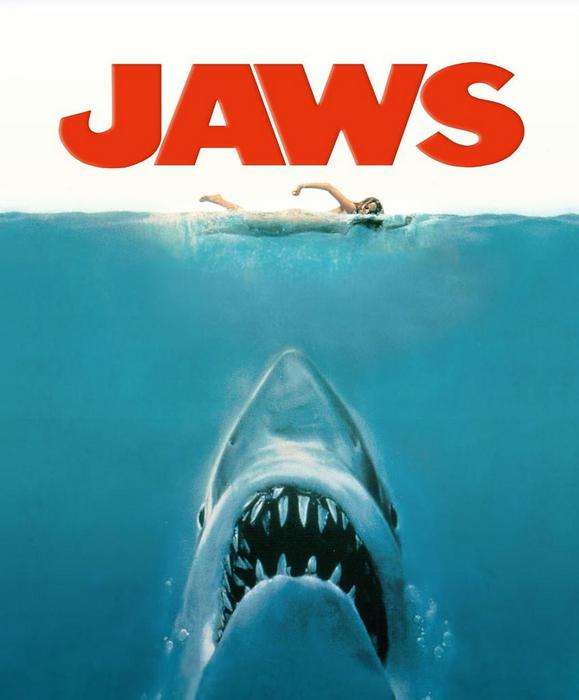

SALT LAKE CITY — “Not all shark attacks are created equal,” asserts a new study published in the Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences. The authors of the study, Christopher Neff and Robert Hueter, were prompted to compile the research because of what they view as the unfair demonization of sharks. They claim these negative perceptions are contingent on the emotionally charged language and images (such as this article’s photo) that often accompany reports of shark encounters.

Neff and Hueter scoured hundreds of studies, newspaper articles, and reports to trace the origins of modern shark terminology. In the study, they point to accounts from the late-1800s and early-1900s that indicate a general lack of knowledge about sharks, with a correlating lack of fear about the risk of attack. They cite an 1865 New York Times article that describes a shark biting a fisherman in Maine. While the article identifies the shark as a “man-eater,” it claims that sharks “seldom, if ever attack mankind.”

Scientific research on sharks grew dramatically over the next few decades, and the study suggests that even as sharks were increasingly in the public eye, people generally didn’t fear them as violent creatures. When a series of fatal shark encounters struck the New Jersey coast in 1916, one expert claimed that it couldn’t have been a shark, because “sharks have no such powerful jaws.” And when a cluster of shark bites occurred in Australia in 1933, the term “shark rabies” was used as a possible explanation, rather than sharks merely having a disposition for attacking humans.

The study claims a turning point in shark perceptions occurred during World War II, as hundreds of thousands of Allied troops were deployed to the Pacific Ocean, “bringing more sharks and people into contact than any previous time in human history.”

According to the study, the military initially downplayed the danger of sharks. The Navy even distributed a brochure called “Shark Sense,” intended to clear up misconceptions and allay sailors’ fears. But the sinking of the U.S.S. Indianapolis in 1945 changed all that. About 900 sailors survived the sinking of the ship, but they had to spend four days in the ocean before being rescued. When help finally arrived, only 317 sailors had survived. Sharks, exposure, and dehydration had claimed the rest. The study says this event “brought the subject of sharks and shark repellents to the forefront of government attention.”

Neff and Hueter assert that the idea of sharks as murderers was cemented in the public mind with the release of "Jaws" — both the best-selling novel in 1974 and blockbuster movie the following year. With this one-two punch, “the criminalization of shark bites was nearly complete: the ‘man-eater’ label implied an intent-driven monster that was seeking human prey.”

Words carry undeniable power, and the study laments that the word “attack” is now used nearly universally for shark encounters, even in cases where a surfboard or kayak is bitten and the person involved escapes unharmed.

To counteract emotionally charged words like “man-eater” and “attack,” Neff and Hueter suggest a more specific way of categorizing human–shark interactions, based on outcomes rather than a shark’s perceived motivations.

Here are the four categories proposed in the study:

- Shark sightings: Sightings of sharks in the water in proximity to people. No physical human–shark contact takes place.

- Shark encounters: Human-shark interactions in which physical contact occurs between a shark and a person, or an inanimate object holding that person, and no injury takes place. For example, shark bites on surfboards, kayaks, and boats would be classified under this label. A minor abrasion on the person’s skin might occur as a result of contact with the rough skin of the shark.

- Shark bites: Incidents where sharks bite people resulting in minor to moderate injuries. Small or large sharks might be involved, but typically, a single, nonfatal bite occurs. If more than one bite occurs, injuries might be serious.

- Fatal shark bites: Human–shark conflicts in which serious injuries take place as a result of one or more bites on a person, causing a significant loss of blood and/or body tissue and a fatal outcome. The study has its critics, many of whom point out that an attack is an attack, regardless of the severity. One blogger from Outdoor Life magazine mockingly wrote that the term “shark attack” is bad because, “labeling a shark attack as a…well…shark attack might confuse the public into thinking the attack was an actual attack.”

Neff and Hueter anticipated this argument and respond in their study with the analogy that most “shark attacks” would be more accurately deemed “shark bites,” just as “we distinguish an aggressive but nonfatal ‘dog bite’ from a serious, sometimes fatal ‘dog attack.’”

What are your thoughts? Should any human–shark encounter be deemed an attack, or should we use more specific language to help remove sharks’ violent stigma?

Grant Olsen joined the ksl.com team in 2012. He covers travel, outdoor adventures, and other interesting things. Contact him at grant@thegatsbys.com.