Estimated read time: 9-10 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

Editor's note: This is the first in a three-part series on World War II ace pilot Grant Turley and the search for his crash site.SALT LAKE CITY — My great-uncle Grant Turley was a fighter pilot during World War II. I’m named after him, and he has always been my hero. At the age of 21, Grant went on a 10-day tear over the skies of Europe and became Arizona’s first ace. Newspapers dubbed him the “Snowflake Storm,” and writer H.I. Phillips dedicated these lines to him in a classic wartime poem:

“Snowflake — there’s one that is new to you —

It’s only a whistle-stop,

But from it Grant Turley is with a crew

That’s making those Berlin hops.”

Grant took part in the first daylight raid on Berlin on March 6, 1944. He was also one of the hundreds of U.S. airmen who perished during that mission. Amidst the chaos of war, my family never knew many crucial details of his death, including where his plane crashed.

Nearly 70 years later, the key to solving these mysteries came in the form of a soft-spoken German aviation expert named Werner Oeltjebruns. This is the story of Grant’s life and how the quest to uncover the truth about his death led me to scuba dive in a lake in northern Germany.

Born to fly

Grant was born in Aripine, Ariz., on June 18, 1922, to Fred and Wilma Turley. As a boy, he was captivated by the exploits of pilots like Charles Lindbergh. “Grant’s earliest desire was to be a flier,” his mother later said. “I think he was born to fly! It seemed to be his only interest in early childhood, as he was always drawing planes, and as he grew older, he spent long hours meticulously making delicate models. He knew the names of them all.”

This love of aviation continued to burn bright, and as a teenager, Grant sent a letter to the commander of the Air Corps inquiring as to which college courses would best prepare him to be a pilot. Grant excelled at Snowflake High School and was valedictorian of his class and captain of the football team. He earned a scholarship to play football at Brigham Young University.

Grant’s college years were interrupted on Dec. 7, 1941, when Japanese forces attacked Pearl Harbor. Feeling a strong desire to join the cause, Grant signed up for private flying lessons in Arizona in preparation for volunteering with the Air Corps. On March 1, 1942, his dream came true when he piloted a plane for the first time.

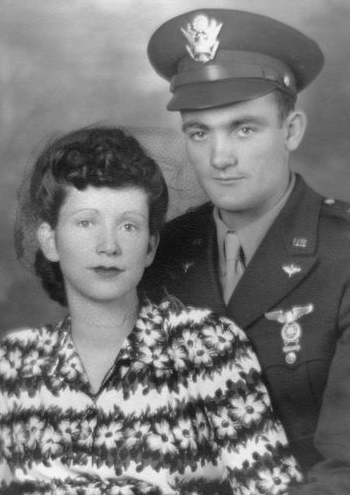

Two months later, Grant took his high school sweetheart, Kitty Ballard, to the local airport to watch planes come in for landings. As they talked and laughed, he surprised her by pulling an engagement ring from his pocket and placing it on her finger. They were married on Aug. 4, 1942, just three days before he shipped out for training in Alabama with the Air Corps. Kitty stayed behind in Arizona.

In the letters he sent home to Kitty during flight training, Grant continually marveled that he was living his dream as a pilot and getting paid to do it. He was assigned to fly the P-47 Thunderbolt. Nicknamed the “Flying Jug,” the P-47 weighed 14,500 pounds — nearly twice the weight of some of the German Luftwaffe planes it would face in combat — and was heavily armed with eight .50 caliber Browning machine guns.

In May of 1943, Kitty traveled to Florida to stay with Grant while he awaited orders. After spending only two months together, the young couple faced a crucial decision. As an officer, Grant was given the option to remain in the States and serve as a flight instructor, or go into combat overseas. Although devastated by the idea of leaving his sweetheart, Grant chose combat. He later told Kitty in a letter:

“My every desire is to be with you, yet there is a something within me which urges me to defend and protect what I know is right. I am defending everything you mean to me.”

On July 23, Grant and Kitty shared a tearful farewell at the train station. Grant wrote in his diary: “A good-bye and Kitty was gone, taking most of me with her. It gave me the most empty feeling I have ever had.”

Grant arrived in Europe on his one-year wedding anniversary. Given the opportunity to choose which fighter group he wanted to join, Grant chose the 78th Fighter Group based in Duxford, England, which was comprised of some of the Air Corp’s most talented veterans and dubbed by one newspaper as the “Big Leagues of Fighters.” Grant’s main role would be as an escort over enemy territory, protecting the massive B-17 Flying Fortress and B-24 Liberator bombers from the Luftwaffe’s brutally efficient warplanes.

Grant named his P-47 “Kitty” and had the name painted just below the cockpit, along with the coat-of-arms from the Sundown Ranch, where he grew up in Arizona. He was anxious to get into combat, but the next three months brought bad weather, canceled missions and frustration. He had never even fired his guns. So when the winter weather finally began to clear in February 1944, Grant took full advantage.

The “Snowflake Storm”

On Feb. 10, Grant was on an escort mission over Germany when 20 German fighters rushed in to attack the bombers. Despite being outnumbered, Grant fearlessly plunged into the fray and zeroed in on a diving Messerschmitt 109. As the plane leveled off, he struck it with a solid burst from his guns. The German plane burst into flames and plunged into the ground. Grant then got on the tail of a second plane and sent it flaming out of the sky.

While thrilled to finally contribute to the war effort by knocking out enemy fighter planes, Grant took no joy in the loss of life. “It worries me that I have caused the death of one man and probably another,” he wrote in his diary that night. “War is hell.”

The following day, Grant scored two more aerial victories on a mission over occupied France. His four aerial victories in two days put him on the verge of becoming an ace. To qualify as an ace, a pilot needed five victories that could be verified by film. Fighter planes like Grant’s P-47 had cameras in the wings, which activated whenever the pilots fired their guns. Officials watched these films after each mission to confirm victories (pilots tended to be overzealous in their reports) and to analyze combat situations.

The press got wind of Grant’s remarkable two-day tally, and he became a sensation back home. A headline in the Arizona Republic dubbed him the “Snowflake Storm,” and he was featured by NBC and other news outlets.

Grant shot down his fifth German fighter on Feb. 20. Only 10 days since first firing his guns, he’d become Arizona’s first ace. He was promoted four days later, and on his first mission as flight leader he shot down a sixth German plane. His commanding officers now considered him one of the most fearless pilots in the 78th Fighter Group.

Bombs over Berlin

In March 1944, Grant was called up as a bomber escort for the first daylight raid over Berlin. At the time, Berlin was the heart of the Nazi war effort and home to a dozen aircraft assembly plants. With the planned Allied invasion of France only months away, crippling the dangerous planes of the Luftwaffe was a critical objective.

Grant and 59 other fliers from the 78th Fighter Group were assigned to protect the 1st Bomb Division on its approach to the German capital.

As dawn broke on March 6, airfields across England came alive with the roar of engines from 814 heavy bombers and 644 fighter escorts. Once assembled, the bomber stream stretched nearly 100 miles from the first plane to the last. One of the largest air raids of the war was underway, headed into the fiercest air and ground defenses Germany could muster. And leading the way was the 1st Bomb Division, protected by Grant and his fellow P-47 pilots.

Grant was in formation with three other P-47s when they saw several enemy planes headed for the bombers and rushed to intercept them. The German planes dived evasively and Grant pursued. Three more enemy planes then pounced on Grant and his wingman. Grant and his wingman split up, each targeting one of the fighters. Grant shot down the Focke-Wulf 190 he’d followed, but in the meantime, the third plane positioned itself behind Grant and let loose with its guns. Grant’s plane was hit several times and he was last seen diving rapidly with the Focke-Wulf 190 on his tail.

Following the dogfight, Grant’s wingman rejoined the formation. Captain May, who was serving as flight leader, later reported that neither he nor the other pilots ever saw Grant’s plane again.

March 6 proved to be the costliest day of the entire war for the 8th Air Force. Along with Grant, more than 230 U.S. airmen lost their lives in the raid.

Aftermath

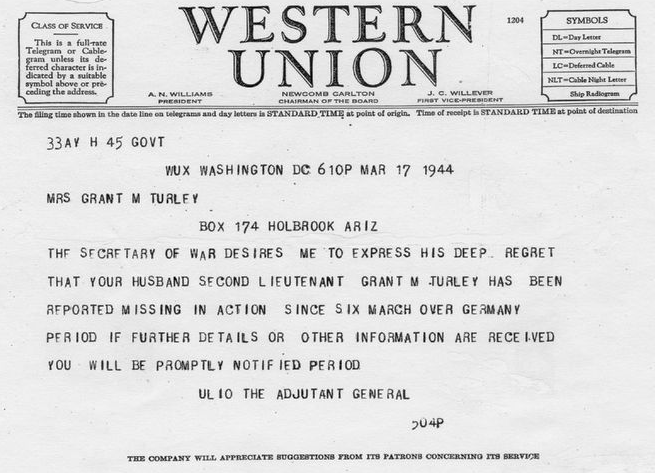

Back in Arizona, Kitty received a telegram on March 17 notifying her that Grant was missing in action. For six grueling months, the family waited for more news.

Kitty was working at the county assessor’s office one day in September when a Western Union representative called to notify her of a telegram. When she asked if they could please deliver it to her, the man said no. They didn’t deliver death messages. Heartbroken, Kitty walked to the Western Union office to pick up the official telegram informing her of Grant’s death.

In January 1946, nearly two years after Kitty first learned Grant was missing in action, news arrived that U.S. military personnel had translated captured German records and located Grant’s body in a prisoner of war cemetery in northwest Germany. Then, in April 1947, Kitty received word that his remains had been transferred to Belgium and interred in the Ardennes U.S. Military Cemetery. His final resting place was Plot D, Row 14, Grave 23.

While Kitty and the Turley family were thrilled to have a permanent grave marker for Grant, the ambiguity surrounding his death gave some a nagging feeling that maybe it wasn’t him in Grave 23. The answer to that question, and many others, was buried in a mountain of military documents.

Read in Part II about how decades later, an aviation expert named Werner Oeltjebruns made exciting discoveries in his effort to uncover the truth. Grant Olsen joined the ksl.com team in 2012. He covers travel, outdoor adventures and other interesting things. Contact him at grant@thegatsbys.com.