Estimated read time: 8-9 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

SALT LAKE CITY — Gov. Gary Herbert issued a state of emergency that went into effect Monday with the worry of growing hospitalizations due to COVID-19 in mind.

The state's leading health care providers have voiced concern for weeks about reaching full hospital capacity. Here's why health care experts are concerned about hospital capacity, especially as the Utah Department of Health reports the highest number of new COVID-19 cases to date.

What a newer statistic tells us about ICU capacity

The state currently reports 446 ongoing COVID-19 hospitalizations, as of Wednesday's data. It's about 3½ times more than it was in mid-September and double the peak of Utah's summer hospitalizations.

All health care providers in the state are reporting a growing number of new COVID-19 hospitalizations, Dr. Michael Baumann, chief medical officer for MountainStar Healthcare, told KSL.com Wednesday. These hospitalizations include the state's biggest hospitals and even rural hospitals.

The state health department provided bed capacity and intensive care unit bed capacity months ago following a summer surge in hospitalizations. It offered a look not just at COVID-19 hospitalizations but all beds used and total available.

As of Wednesday, 76% of the state's ICU beds were used. It remains over the state's target threshold of under 72%. It's dangerously close to the capacity hospitals are comfortable with and some hospitals have been at full capacity for weeks.

But the state's health care providers say the statistics don't tell the full story of why leaders are concerned with hospitals. The state health department recently included referral center ICU beds to its data dashboard. These are the hospitals best equipped to handle COVID-19 patients with the harshest symptoms and also the largest non-coronavirus critical care needs.

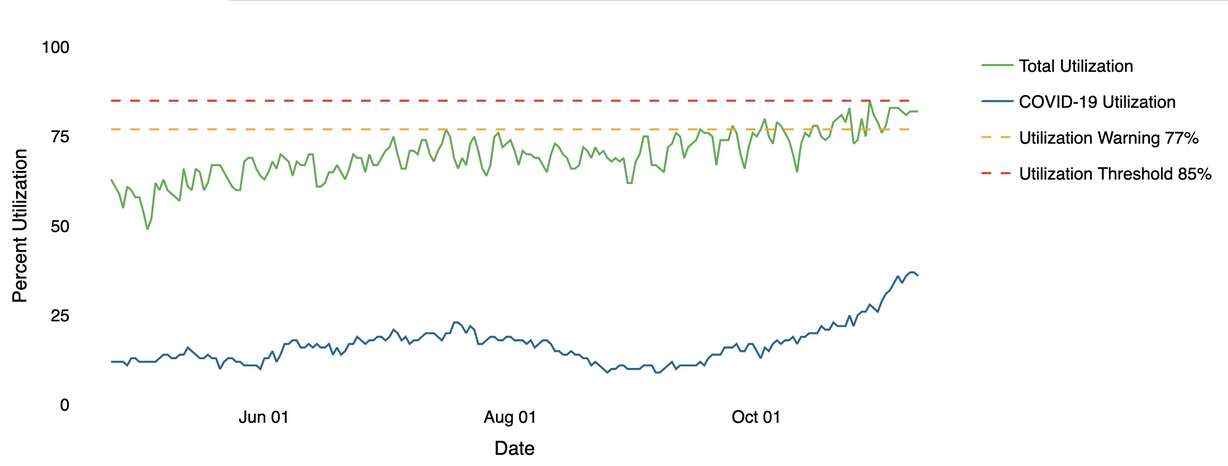

The ICU bed capacity at referral centers is 82% and hovering between what the health department describes as the state's utilization warning (77%) and utilization threshold (85%) nearly every day since October. These numbers are essentially the moment ICU beds become maxed out.

"Once you get to 80-85% even in a non-ICU, the ability to move patients through the hospital and through the system, including through the ICU, becomes very difficult," Baumann explained.

Think of it like it's a restaurant. Once a restaurant nears capacity, it's difficult for them to bring in more customers. Even when someone leaves, there's time needed to set up the table. If a customer hangs out longer than staff expects, it means a longer wait time for a customer waiting to be seated.

Related:

"The same thing happens at a hospital," he continued. "You get people you don't anticipate staying as long at the ICU or on the floor and things just grind to halt the higher number of occupancy."

Health care leaders have also asked the state to provide other data to better depict the situation hospitals are facing, Baumann added. These statistics would include non-referral center ICU capacity.

Bed percentages can also be misleading because it doesn't include staff available to care for a patient. Bed capacity might be listed at 75%, but it's possible that there are fewer beds available with adequate staff to treat the patient. That's why health care leaders would also like the state to provide the percentage of "staffed-beds" available.

How new cases could turn into new hospitalizations

One of the leading arguments against the seriousness of COVID-19 is the mortality rate. And, yes, Utah's mortality rate is good news. Through the end of October and into November, about 99.5% of people infected in the state have survived. This number, of course, doesn't include short or long-term complications due to COVID-19.

In addition, only about 4.5% of COVID-19 cases in Utah to date have led to hospitalizations. That's also a good sign, as it was steadily around 8% at the beginning of the pandemic. But as Utah medical experts point out, the low chance for a worse outcome of the coronavirus doesn't offer much help to hospitals when the total number of new cases continues to climb at rapid rates.

As these numbers go — the number of positives — more and more people will end being admitted, and more people are potentially put at risk of dying.

–Dr. Michael Baumann, chief medical officer for MountainStar Healthcare

Let's say Utah's hospitalization rate remains steady at 4.5% with a mortality rate of 0.5%. Now plug in, as an example, Utah's seven-day running average of 2,584 new COVID-19 cases per day, as of Wednesday. The current trends say it would eventually lead to about 116 new hospitalizations and 13 new deaths every day there were 2,584 new cases.

It would drive up total hospitalizations due to COVID-19 further and make treating every patient that needs hospitalization a little more difficult.

"As these numbers go — the number of positives — more and more people will end being admitted, and more people are potentially put at risk of dying," Baumann said. "The large numbers are very disconcerting for this, leading to more hospitalizations and deaths in Utah that we could prevent."

One of the concerns is that the state health department COVID-19 numbers show consistent spread among age groups. The state lists six age groups between the ages of 1 and 85 and over. All six age groups experienced between 61% and 87% growth over the past month, which shows virus spread is pretty even among age groups.

Previous upticks during the summer and early fall centered around younger individuals, who were less susceptible to have worse outcomes like hospitalization. Since Oct. 10, cases involving the 25 to 44 and 45 to 65 ranges each spiked 68%, the 65 to 84 range grew 72% and the 85-plus range rose 79%. Older age groups are more likely to end up in a hospital.

Medical professionals were quick to assert that this doesn't even account for pre-existing conditions, which may also factor in hospitalizations. The state provides those stats only after an individual is hospitalized.

That said, COVID-19 isn't the only issue in play for hospitals.

Additional hospitalization concerns

ICU figures provided by the state account for all needs, from COVID-19 to car crash injuries and heart attacks. It's representative of all cases where someone needs critical care.

There are already some sacrifices made to keep hospitals afloat. Herbert acknowledged Monday that Utah hospitals recently began to turn away patients from neighboring states like Idaho, Montana, Nevada and Wyoming. The Wasatch Front is home to the nearest research hospital for many places outside of Utah, which is why many patients are sent to Utah for care.

Utah's seemingly never-ending COVID-19 rise in cases since mid-September comes at a traditionally tough time for hospitals for other reasons. Temperatures are dropping as the seasons shift to winter and the normal flu season.

"Generally speaking, fall and winter are much higher in terms of volumes for hospitalizations because of seasonal infections; pneumonia admissions are increased throughout the fall and winter; there are a lot of non-COVID-related medical problems that also tend to be more common during the fall and winter," said Dr. Brandon Webb, an infectious disease physician at Intermountain Medical Center.

Every new COVID-19 hospitalization makes it more difficult to handle all other hospitalizations.

As KSL.com reported last week, flu numbers are down early this year despite a rise in testing. The state reported its first two influenza hospitalizations in the final week of October. Per Utah Department of Health statistics, flu hospitalizations are normally low until about December, where they rise and remain its highest over the winter months before dropping in March.

Related:

Since the 2015-16 flu season, peak flu hospitalizations have ranged between a low of 3.99 per 100,000 during the 2019-20 season (roughly 127 hospitalizations) to a high of 8.19 per 100,000 (roughly 254 hospitalizations) during the 2017-18 season. These peaks also ranged from December, at the earliest, to February, at the latest. Similar trends can be found throughout the country, per Centers for Disease Control and Prevention statistics.

Baumann pointed out that since COVID-19 and the flu are spread in similar ways, COVID-19 guidelines also help stop the spread of the flu. If Utahns practice COVID-19 safety guidelines, it's possible the state won't experience many flu cases this winter. It happened to many southern hemisphere countries during their winter, June through September.

Winter is also when other medical episodes, like heart attacks, are more likely to occur, according to research. That's due to cold exposure that clamp blood vessels down, overexertion and overheating in the cold, and the flu, according to an article published by the Harvard Medical School.

"Cold weather sometimes creates a perfect storm of risk factors for cardiovascular problems," Dr. Randall Zusman, a cardiologist with Harvard-affiliated Massachusetts General Hospital, told HMS in 2016.

Given possible and likely non-coronavirus hospital needs in the coming months, Utah medical experts again plead for people to follow guidelines set up by the state to limit the spread of COVID-19.

That's why they urge people to wear face coverings, practice physical distancing and avoid going outside when they are sick.

"The reason we're all being asked to pitch in and do more right now is to help offload the hospital systems so that we can continue to care for the vulnerable patients in our community," Webb said. "We recognize that it is tough for everyone to do a little bit more. It is tough to follow more restricted social behaviors, but we really appreciate it."