Estimated read time: 4-5 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

SALT LAKE CITY — Mike Conley has heard the story of what happened in Memphis In 1968. Two Black sanitation workers were forced to work in torrential rain and took shelter in the back of their garbage truck. An electrical switch malfunctioned. The compactor turned on. The men died.

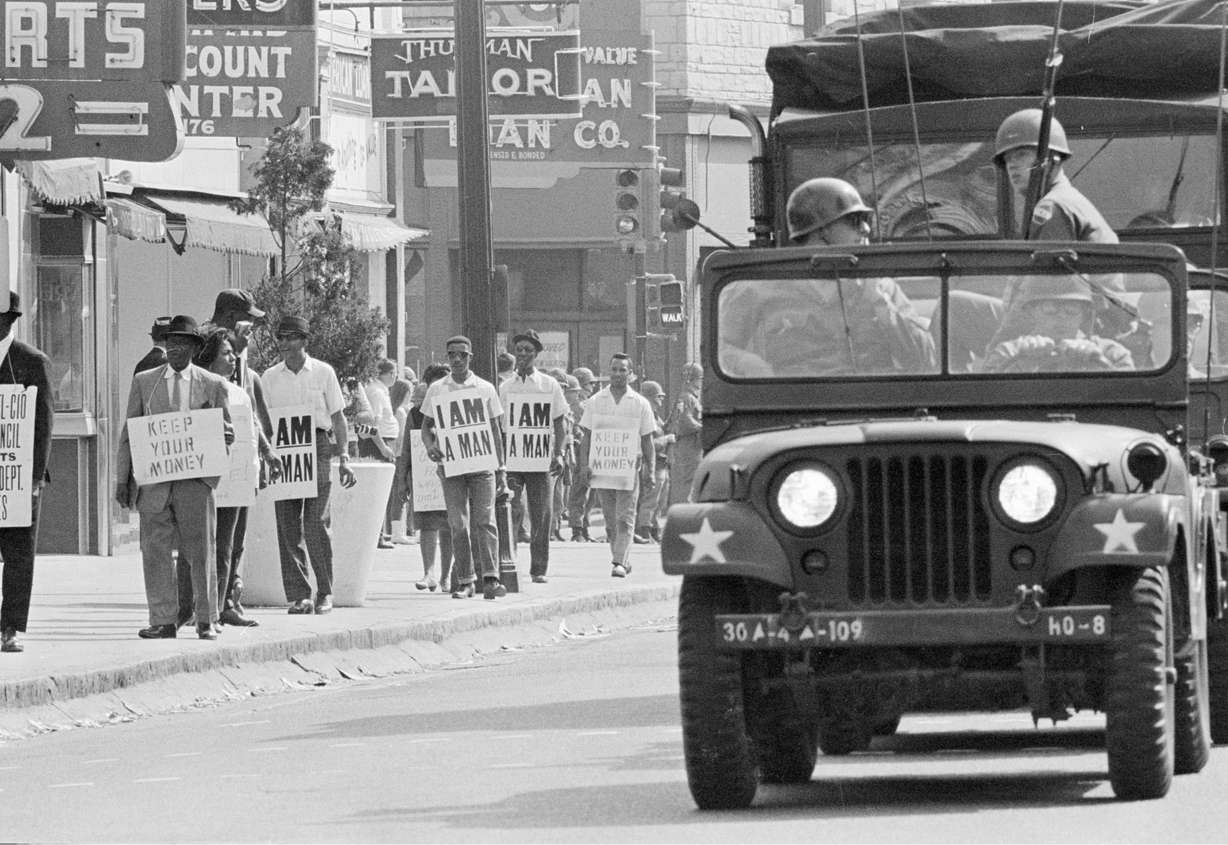

Conley has seen the pictures of the sanitation workers — all of whom were Black — walking the streets of Memphis with signs reading "I Am a Man" draped around their necks. Eleven days after the deaths, more than 1,300 sanitation workers went on strike, protesting poor working conditions, low pay, and discrimination by the city.

It was a strike that is remembered for being a time when a group of oppressed Black men stood up for themselves. It's also a strike that led to the assassination of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

When the NBA restarts on July 30, Conley's jersey will say the same thing as the signs worn by the demonstrators over 50 years ago: "I Am a Man."

"It was something that I kind of consulted with my family with and something that we thought was powerful, especially being where that all came from was actually in Memphis," Conley said.

In an attempt to keep the focus on the social injustice movements that have spread throughout the nation, the NBA is allowing players to select an approved message to wear on the back of their jersey. For some, like Conley, the messages are personal.

Conley famously ingrained himself into the city of Memphis. He started charities there, donated money, and, yes, he learned its history — including the important chapter in 1968.

According to the King Institute at Stanford University, sanitation workers earned wages so low many were on welfare and food stamps to feed their families. The men worked long hours with no overtime pay. They didn't get sick leave. If they were injured on the job, they could be fired.

The workers demanded increased wages, for inhumane conditions to be improved, and for the city to recognize their union. Those demands fell on deaf ears by then-mayor Henry Loeb III, and he issued an ultimatum for the men to return to work. Most didn't — and some reports say more than 10,000 tons of garbage piled up in the city.

"We felt we would have to let the city know that because we were sanitation workers, we were human beings. The signs we were carrying said 'I Am a Man,'" James Douglas, a sanitation worker, said in an American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees documentary. "And we were going to demand to have the same dignity and the same courtesy any other citizen of Memphis has."

It became more than a strike; it became a social struggle — and it won the support of King.

On March 18, 1968, King spoke to more than 25,000 people gathered at the Bishop Charles Mason Temple, saying: "You are reminding this nation that it is a crime for people to live in this rich nation and receive starvation wages."

Ten days later, King led what was supposed to be a peaceful demonstration in Memphis, but the protest took a violent turn when an estimated two hundred participants began breaking storefront windows and looting. That resulted in police killing a 16-year-old.

Troubled by the violence, King returned to Memphis determined to lead a successful peaceful rally. On April 3, 1968, nearly two months after the start of the strike, King gave his final public remarks, the now-famous "Mountaintop" speech, at the Mason Temple.

"I just want to do God's will. And He's allowed me to go up to the mountain," King said. "And I've looked over. And I've seen the promised land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the promised land."

The next evening King was assassinated. On April 8, in response, 40,000 people participated in a silent march through the streets of Memphis. Eight days later, the Memphis city council voted to recognize the union and promised higher wages to the Black workers.

The strike was over. But over 50 years later, in many ways, the search for the promised land King spoke of still continues.

"It meant a lot to me to be able to put that on the back of my jersey," Conley said. "And just represent all those behind me."