Estimated read time: 5-6 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

SALT LAKE CITY — Jon Owen didn't realize there was anything wrong with his son, even though Ben, then barely 18 months old, didn't sleep well or sit up or babble like other children his age.

But their trusted pediatrician noticed what the Owens did not and sent Ben to a specialist. Soon after, the Owens found out that Ben showed signs of developmental delays and, possibly, autism.

"On the one hand, just hearing the word 'autism' can be pretty scary," Owen said. "But on the other hand, putting a name to something is really good."

More and more children are receiving screenings for autism at a younger age, according to a study led by researchers from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

That's "just what we want to see," according to Deborah Bilder, an associate professor of psychiatry at the University of Utah, and the paper's second author.

Bilder, who is also the medical director of the Neurobehavior HOME program, said earlier diagnosis means earlier access to treatment.

"Even if at that time they're not recognized as having autism spectrum disorder, if they have deficits socially, they can access these services that help them," Bilder said.

The study, released Wednesday, is the first to look at the impact of guidelines released by the American Academy of Pediatrics in 2007. That year, the academy recommended that all children get screened for autism at 18 months and 24 months of age.

The announcement came on the heels of the CDC's first major study on autism prevalence. With growing public awareness and better diagnostic tools, researchers now believe up to 1 in 45 children in the U.S. is diagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder.

"Autism was not as rare as we thought it was," Bilder said.

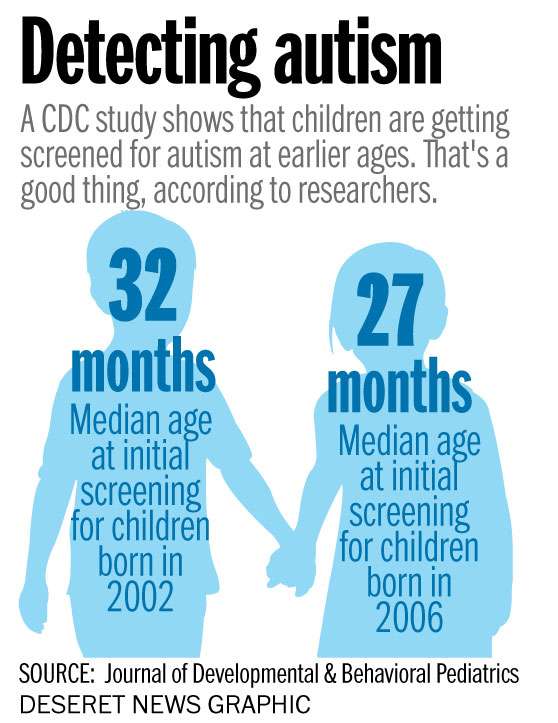

The study, done in collaboration with the Utah Department of Health, compared children born in 2002 to those born in 2006 — right before the screening guidelines changed.

It found that the median age of initial screening dropped from 32 months to 27 months in those four years.

Benefits of early intervention

Earlier intervention is more effective and less costly, according to Julia Hood, director of the Carmen B. Pingree Autism Center of Learning.

"There's this critical time for individuals where they can learn some of these skills, particularly language skills," Hood said.

That time frame is between 3 and 6 years old, when the neural circuits in the brain are more easily molded. Those brain connections, responsible for learning and behavior, become increasingly difficult to change the older a child gets. It's the same science that explains why children who are exposed to a second language when they are very young can pick it up more easily and hold onto it well into adulthood, Hood said.

There is some controversy over whether universal autism screening for infants and toddlers is backed by enough evidence. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force made waves in August when it concluded there was not enough evidence to recommend that every young child be screened for autism spectrum disorder. The task force said more research was needed to conclude that early screening helped.

The earlier we can identify it and get people looking for services, the more likely they'll get the help they need.

–Julia Hood, Carmen B. Pingree Autism Center of Learning

Many doctors responded by saying that autism was common enough, and that early behavioral therapy was effective enough, to warrant universal screening.

It can seem people are looking for signs of autism at unusually young ages, Hood agreed. "I have a 5-month-old and he's already asking me about some of those early markers," she said, referring to her pediatrician.

But though it can seem early, kids can be diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder as early as 18 months, she said. By 2 years old, many can be reliably diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder, according to the CDC.

Yet early diagnosis of children is often delayed until school age, when they are 3 or 4.

By that time, Hood said, there could be a delay in getting much-needed autism services. About 200 kids are on the wait list for the Pingree center, meaning that some families have been waiting for a slot for a year and a half now.

"The earlier we can identify it and get people looking for services, the more likely they'll get the help they need," Hood said.

Help for parents

Even with early diagnosis, access to quality preventive care can be a problem, particularly among minorities, experts say. The study found that Hispanic children had a lower-than-expected prevalence of autism, suggesting that they weren't being identified.

And even though the idea behind earlier screenings is to open the gates to earlier treatment, that can be expensive.

For a year, Owen and his wife resisted a diagnosis of autism for their son, based on what Owen now calls "bad advice" from a child psychiatrist.

"We were told that insurance didn't cover autism and it would break our family's finances if we tried to get therapy," he said.

That was more than five years ago, when insurance companies weren't required to cover autism services.

But last year, Utah joined 34 other states that require insurers to cover autism treatment in their health care plans. That coverage kicks in in January. Last year, Medicaid also started covering autism services for children up to age 21 in the fall.

#autism_graph

That's going to make a big difference for a lot of families, Owen said, even though he and his wife didn't get those benefits.

They eventually decided to get the official autism diagnosis for their son. Owen and his wife then refinanced their home to pay for a year at the Pingree center. The waiting list was 18 months.

But once there, Ben bloomed.

Owen will never forget the day Ben came home and said, "I love you, Mommy."

"Consider that he never really said a sentence before he went to the Pingree school," Owen said.

Of course, he added, Ben said it to him, not to his mom.

"But it was a really great step," Owen said, laughing.

Daphne Chen is a reporter for the Deseret News and KSL.com. Contact her at dchen@deseretnews.com.