Estimated read time: 11-12 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

SALT LAKE CITY — By 1967, Andy Warhol’s famous painting of Marilyn Monroe and Campbell's Soup cans already had the art world calling him the "Father of Pop Art." So, the University of Utah may have thought it pulled a "coup" when Warhol accepted its invitation to speak to students about his art.

“I never really had met a big, famous artist before,” said Joe Bauman.

In October 1967, Bauman got the plum assignment he wanted — an interview with Andy Warhol for the Daily Utah Chronicle.

“I knew who Andy Warhol was, but I didn’t know how he looked,” remembered Bauman. “I was very impressed with somebody with a national following in the arts … and I thought this is a great thing. He’s coming to ‘little’ Utah, and he’s a guy that’s on top of the New York art world.”

The plum assignment turned a little sour for Bauman when he tried to snap a picture of Warhol during the limo ride from the airport.

“This manager of his says, no, no, no, no — Andy is very shy, he’ll be really offended,” Bauman said. “You’re not to take any pictures of him."

I kept thinking this is insane. I’ve come all the way out here to get a good picture of Andy Warhol. I’m not going to go back without one.

Bauman remembered Warhol would hardly say anything aside from vague murmurs to questions. Bauman handed Warhol a Daily Utah Chronicle article previewing Warhol's own lecture that night. Then, from the back seat, Bauman turned the lens of his Mamiya C3 twin lens reflex camera toward the unknowing Warhol and focused the shot.

“I don’t look at him after a while and I go — snap — and I get the picture,” said Bauman. Neither Warhol nor his manager, Paul Morrisey, noticed. “I felt that was a pretty good coup.”

The limo took Warhol and his manager to the Hotel Utah.

The lecture, billed as “Andy Warhol: Pop Art in Action,” was to begin at 8 p.m. that night, Oct. 2, at the University of Utah’s Student Union Ballroom. Newspaper ads at the time said the lecture was to be illustrated with Warhol’s “famous motion pictures.” Students paid $1 for their tickets. Non-students paid $1.50. Reserved seats sold for $2.

Over 1,100 people showed up for the lecture. Bauman was there, hoping for another opportunity to talk with Warhol for his Daily Utah Chronicle story. Warhol and his manager, Morrisey, showed up about 40 minutes late.

“They had their projector cord strung all across the middle of the hall, they’re trying to set things up,” remembered Bauman. “There’s a lot of blundering around — not quite knowing what they’re doing.”

“At first they had audio-visual difficulties,” said Angelyn Hutchinson. Hutchinson, a freshman reporter for the Daily Utah Chronicle, was also there. She wasn’t there on assignment. But she wanted to see Andy Warhol for herself. “They tried to show this black-and-white film, and then he was going to answer questions.”

Archives from the univesity’s Office of Lectures and Concerts peg the movie as Warhol’s 1967 film “****,” a 25-hour-long movie that was only screened in its entirety once. Warhol’s audience that night saw about 40 minutes of it.

“I think it was little bits and pieces and rejected stuff from different films they kind of taped together,” said Bauman. “But the lecture itself was awful.”

In the Q-and-A that followed the movie, Warhol, wearing a dark coat and dark sunglasses, only offered up brief — and what many remember as mostly monosyllabic answers — to questions from the crowd.

“He was just sort of noncommittal most of the time,” said Bauman.

“He gave these really inane answers, or hardly any answer at all. People left pretty disgusted with the whole thing,” remembered Hutchinson. “Somebody asked him how he started his films, and he said something like, ‘In the beginning I think.’ Just really dumb stuff like that.”

Things didn’t go any better for Warhol at an art faculty dinner held upstairs in the Student Union in his honor following the lecture. Warhol, still in his dark sunglasses, sat mostly quiet.

“I was at this dinner with all these professors,” remembered Bauman. “There’s this real chill of hostility in the air.” Bauman says some of the questions from one of the art instructors became particularly hostile.”

“He said, ‘Now, your Marilyn Monroe print, that’s upstairs in the Museum of Modern Art, right?” Bauman said of one such question. When Warhol answered yes, Bauman said the instructor kept needling the “Father of Pop Art.”

“What floor is it on? Isn’t it on the thirteenth?” Bauman remembered the professor asking.

“Oh yes, it’s on the thirteenth,” Warhol reportedly responded.

“Hah! There isn’t a thirteenth floor!” retorted the instructor according to Bauman.

“At this, Andy was very insulted,” said Bauman. “So, Andy and us sycophants all jump up and all stomp out of there. Then we go to this party on the west side in somebody’s kind of abandoned apartment.”

An editorial cartoon appearing in the Daily Utah Chronicle summed up the campus consensus that Warhol bombed the lecture: It shows the pop artist scrambling to take refuge from angry students in a fictitious “Canbull’s” soup can labeled, “Rotten Tomatoes.”

Suspicion begins to surround Warhol's visit

The bad press would soon turn even more rotten for Warhol.

“Apparently, a couple of professors went to the director of lectures and concerts, Paul Cracroft,” remembered Hutchinson, “and told him they didn’t think it was Warhol.”

One of the art professors told Cracroft he had actually met the real Warhol at a party in New York a year-and-a-half earlier. He was certain the man who spoke was not the Andy Warhol he met.

“The next morning, I go to the ‘Chronny’ to write my story,” remembered Bauman, “I was asking — how many inches can I have? I’ve got to get this ready right now! I was told just to hold the story — there are some suspicions about this man.”

“He (Cracroft) was trying really hard to get some confirmation — was it Warhol or not,” said Hutchinson.

“I was angry,” said Bauman. “I’ve gone through a lot of effort and I have a really great story about partying with Andy Warhol and stomping out of the faculty dinner. And, I thought this was going to be a great article.”

Cracroft refused to pay Warhol’s $1,000 speaking fee to his Boston-based booking company, American Program Bureau, until he got confirmation.

“We (Daily Utah Chronicle) started to look into things,” remembered Hutchinson. “It’s not like today where you can ‘Google’ somebody and find hundreds of images of them. You can even go to the library to find a lot of images. We’re talking about the days of the standard typewriter. You had to wait for your subscription magazines from New York. There weren’t a bunch of profile or close-up photos of Warhol around.”

Hutchinson said the Chronicle made requests from New York media outlets for Warhol photos.

“In fact, the other reporter and I who worked on it (the story), Kay Israel, wrote a letter to the New York Times of all places,” said Hutchinson, “and asked if we could have a close-up picture of Warhol. They, of course, did not respond to this student newspaper.”

Well, Andy doesn't like to speak in public and he just thought Midgette was better looking, would offer a better lecture than he would. The double was better for public consumption.

–Angelyn Hutchinson, a freshman reporter

Still, the evidence that an imposter Andy Warhol had come to the U. continued to grow. At the end of October, a New York-based photographer came to Salt Lake to take photographs of the University of Utah Repertory Dance Theater for national publications.

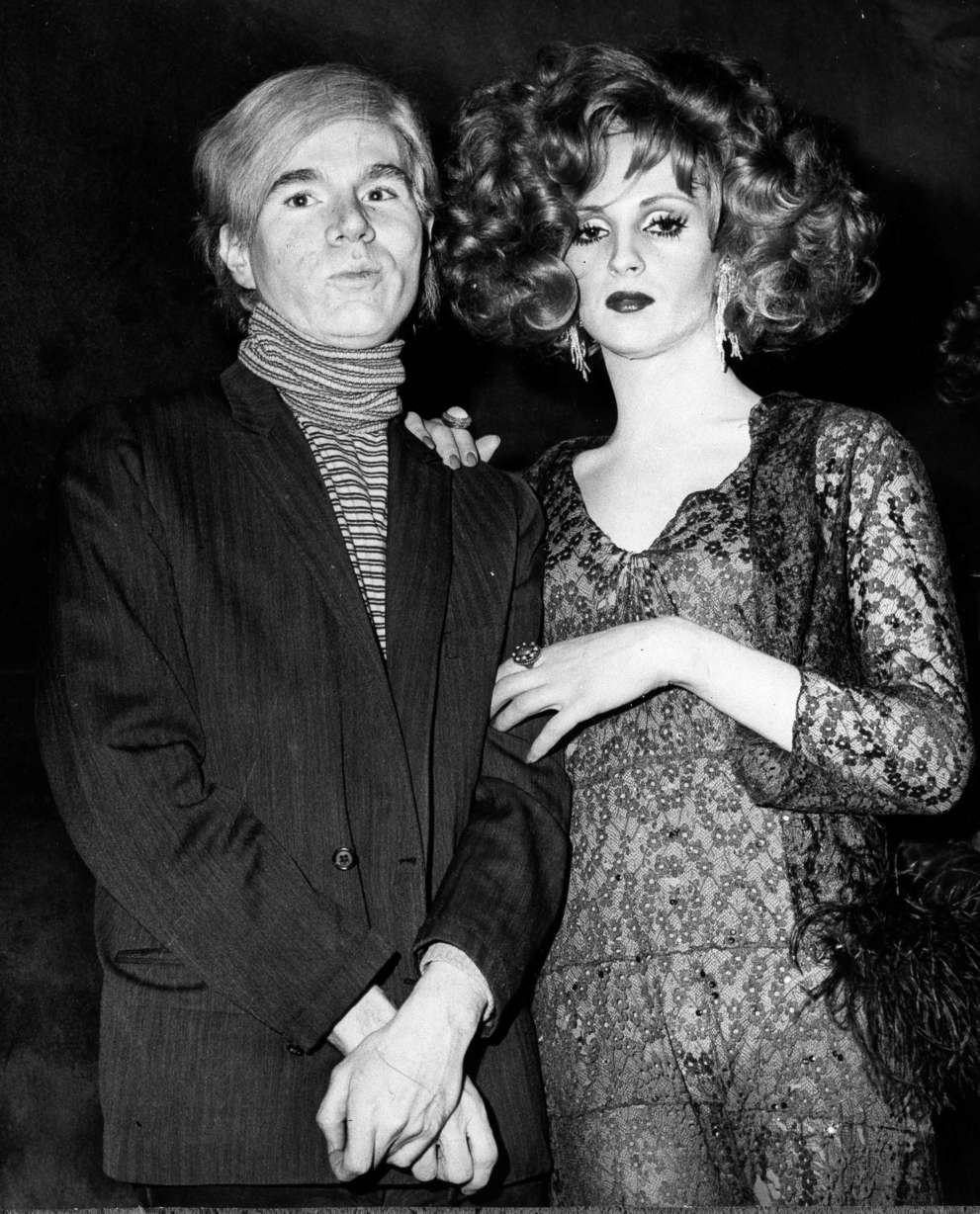

“Paul Cracroft showed the picture Bauman had taken of the supposed Warhol to this guy,” said Hutchinson. “And he said, ‘No, that’s not Warhol. I know Warhol and that’s not Warhol.’ ”

In early December 1967, Cracroft was to go to New York City on an unrelated business trip. He contacted Warhol’s manager, Paul Morrissey, and asked if he could meet him and Warhol while there.

“They said, ‘oh, of course,’ ” remembered Hutchinson, “and they stood him up.”

In a letter sent to Morrissey, Cracroft wrote, “Neither of you chose to take advantage of an excellent opportunity while I was in New York, so I have no other choice but to continue to hold up the $1,000 check.”

Then a few weeks later, a University of Utah student returned from New York with a real Andy Warhol photo from the Village Voice.

“We ran Joe’s photo and the photo of the real Warhol,” said Hutchinson, “and asked the students to weigh in.” Hutchinson said the general consensus was the guy who came to the U. was not the “Father of Pop Art.”

“It was obvious it wasn’t Andy Warhol,” chuckled Bauman.

The Daily Utah Chronicle stepped up its pressure.

“We were calling his manager several times a day,” remembered Hutchinson. “We contacted the other universities where he (Warhol) appeared in the West.”

When the Warhol people started getting calls on the true identity of the Andy Warhol who spoke at the University of Oregon, the confession finally came.

The truth

“There was enough coming out,” said Hutchinson. “When he (Warhol’s manager Paul Morrissey) finally confessed, it was like, OK, you guys finally bugged me enough. Yeah, it wasn’t Warhol.”

Morrissey said Warhol had sent an impostor to Utah and three other schools: the University of Oregon, Linfield College (also in Oregon) and the University of Montana. And Morrissey said the man who passed himself off as Andy Warhol was actor Allen Midgette. Midgette had acted in some of some of Warhol’s films, including “****,” knew Warhol’s mannerisms and could imitate his voice. Morrissey referred to the hoax as an experiment.

“We asked him why did you send this impostor?” said Hutchinson. “ ‘Well, Andy doesn’t like to speak in public and he just thought Midgette was better looking, would offer a better lecture than he would.’ ” Morrissey said Warhol thought the double was better for “public consumption.”

“He was very reluctant to own up to what he had done,” said art historian Scotti Hill. “It took quite a bit of digging and insistence on behalf of the Daily Utah Chronicle to finally to get him admit to this.”

The 1967 lecture was the focus of Hill’s 2011 thesis, “The Artist is Not Present.” She frames the lecture as a piece of performance art. She says the episode is very similar to the real Warhol’s body of work about the nature of consumerism and flashy, attractive imagery.

“I think the point here,” said Hill, “is that it can be a soup can, it can be an actual human being. It’s very akin to his celebrity portraits where it’s less about the personality of the subject and more about the veneer — the public spectacle.”

“If you think about it,” said Hill, “a very famous, well-known figure plans a college lecture tour and does not actually show up at four separate universities and only one of those universities notices — that is a justification of his (Warhol’s) point that people are so interested in the persona and less interested in the actual substance they’re there to learn about.”

Hill said she believes Warhol crafted a really creative idea that isn’t going to sit well with everyone. But she believes the ill-fated lecture adds to Warhol’s appeal as an artist.

“He’s not just creating interesting paintings and sculptures and films, but also performance pieces that really toy with his audiences,” said Hill. “In this case, it really makes him much more of a complex figure and someone who will continue to elicit scholarship in these areas.”

Nearly 50 years later, both Hutchinson and Bauman believe the lecture to be more of a hoax than a piece of performance art.

“He obviously had an impact on the art world, but to me, it’s still a hoax,” said Hutchinson. “I personally think he didn’t like to speak in public and didn’t want to come West, and thought he could get away with it. He decided to try to pull the wool over everyone’s eyes.”

Neither Hutchinson nor Bauman think Warhol was scheming for money.

“I had a feeling he had been invited, and he accepted, to go on this tour and he just didn’t feel like going,” said Bauman. “And this other guy was willing to impersonate him.”

Bauman said sometimes you have to separate a person’s art from their personality.

“I chalk it up to one of the idiosyncrasies of Andy Warhol,” he reflected. “The more I’ve come to see his art, the more I’ve admired it.”

Through his manager, Warhol did offer to make a bona fide appearance at the University of Utah. Cracroft declined, explaining the school already had its fill of Warhol — real or otherwise.