Estimated read time: 6-7 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

SALT LAKE CITY — Throughout the spectrum of Earth’s varied environments, we find numerous different habitats, and inside every habitat, we find numerous pocket environments. And inside those pocket environments, we invariably find species of organisms perfectly adapted to live there, as comfortably as a round pegs in round holes.

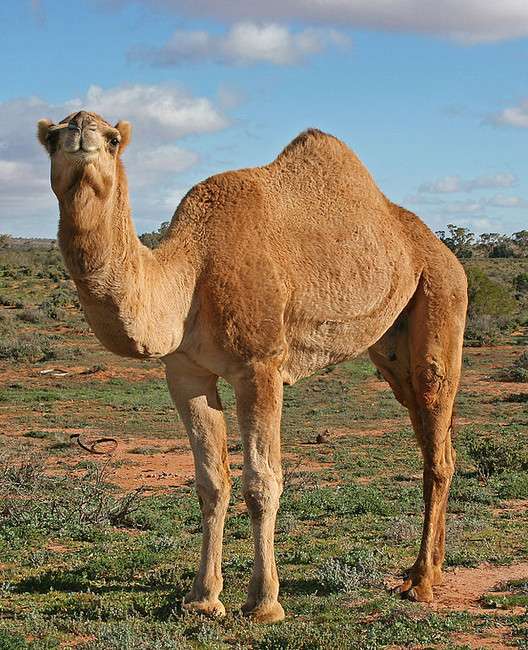

If some environments can be represented by a round hole, then the deserts of northern Africa and the Middle East, which have some of the harshest environmental conditions on the planet, is a hexagon, and few plants, and even fewer animals, can fit into such a complex shape. But the camel is the hexagon peg to the desert’s hexagon-shaped hole.

“Camels are perfectly suited to live in some of the harshest conditions in the world,” says Mike Kuhn, a zoo keeper at the San Diego Zoo who works closely with the camels. “Without every adaptation in a camel working together, (camels) would not be able to survive in their environment.”

Because camels evolved in harsh desert environments, they have developed a number of specialized physiological structures allowing them to cope with heat and dehydration more efficiently than any other creature on earth.

Camels are most famous for their distinctive humps. There are two species of camels: the dromedary, native to west Asia, which has one hump; and the Bactrian camel, native to central and east Asia, which has two humps.

The biggest misconception regarding camels is that they store water in their hump. The humps are actually a reservoir of fatty tissue.

Whereas other mammals distribute their fat cells evenly across their bodies, camels concentrate all their fat cells in their hump. Concentrating fat in a central location eliminates the insulating layer of heat-trapping fat, thus allowing for excess body heat to more easily escape.

This is just one of several specialized adaptations the camel possesses that help it survive in harsh, hot conditions.

Camels don’t actually store water any more efficiently than animals, they are just much more efficient at not losing it than other animals, and they’re better at thriving when they’re dehydrated.

During long expeditions, a camel may lose 25 to 40 percent of its body weight due to sweating. Most mammals can’t lose more than 15 percent before dying of cardiac failure.

And a camel maintains plasma volume at the expense of bodily tissue fluids. But even so, on long, dry journeys, the animal's blood will grow increasingly viscous. No other mammal could live with blood as thick as that of a camel in a severely dehydrated state. What makes this possible is the shape of a camel’s red blood cells.

A camel’s red blood cells have an oval shape, unlike other mammals, which are circular. The advantage of having oval blood cells is that they continue to flow through the bloodstream after a camel becomes dehydrated. Circular blood cells clump together when plasma levels drop too low, and these clumps form clots that cause heart attacks and strokes.

And oval blood cells have a second advantage over circular blood cells: They can withstand high osmotic variation, making them much less likely to burst when a camel drinks a large quantity of water. Oval red blood cells are also found in reptiles, birds and fish, but camels are the only mammal to have them.

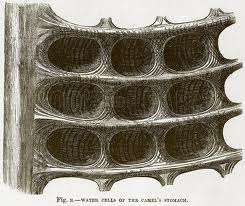

Camels drink very large amounts of water in one session to make up for previous losses. They can do it without suffering osmotic problems because the water they drink is released from their stomach and intestines very slowly, allowing time for equilibration in the bodily tissues. In other mammals, such large intakes of water would cause their rapidly rehydrating red blood cells to burst, according to Marisa Montes in "All About Camels."

A camel’s kidneys are the most efficient on earth. Very little moisture is lost in camel urine. Camel urine can be as thick as syrup and have twice the salt content of sea water, and a camel’s fecal pellets are dry enough to burn immediately upon voiding.

Another one of the camel’s most impressive adaptations is its ability to regulate its body thermostat. This unique thermostat allows body temperature tolerance level to raise as much as six degrees. Most mammals will start perspiring when their body temperatures rise over 99 or 100 degrees, and they will start experiencing organ failure as body temperature exceeds 104 degrees. A camel’s body temperature can get as high as 106 degrees before it even starts to perspire.

A camel’s long legs are another physical adaptation against the heat. Their long legs keep them above the most intense layer of heat rising from the ground. An adult camel stands six feet tall at the shoulder, seven feet tall at the hump.

Camel’s have very thick coats. It seems counterintuitive, but a camel’s thick coat insulates it from heat radiating from the desert sand. A shorn camel sweats 50 percent more to avoid overheating.

Camels are such efficient users of moisture that they can actually increase their water intake in situations where other animals can’t. Camels eating green plants can extract enough moisture that they actually increase their bodies’ hydration, Montes writes.

Camels have specialized nostrils that allow them, by breathing through their nose, to cool down incoming air to the point that moisture in its outgoing breath is condensed back into moisture. The camel swallows the recaptured water, rather than exhaling it. Camels can close their nostrils against blowing sand.

Camels have very tough mouths, enabling them to eat rough, thorny bushes without damaging the lining of their mouths. And they have three stomachs. Camels tend to gulp down their food quickly without chewing it, a necessity during long trips across the desert. The food is regurgitated later, like cattle, and chewed in cud form. They are more efficient at extracting protein and energy from poor-quality forage than any other ruminant.

A camel can go up to a week with little or no food and water, and lose a quarter of its body weight, without impairing normal bodily functions.

A camel can go up to a week with little or no food and water, and lose a quarter of its body weight, without impairing normal bodily functions.

Camels have a double row of eyelashes, and thick ear hair, giving them added protection against blowing sand and dust. They have broad, flat feet which prevents it from sinking into soft sand.

It is believed that frankincense traders first domesticated the camel thousands of years ago to make the long and difficult journey from southern Arabia to the northern Middle East.

Llamas, native to South America, also belong to the camelid family. Scientists believe that today’s camel and llama evolved from a common ancestor that lived in North America about 40 million years ago. It’s believed that the group that became the dromedary and Bactrian camels migrated across the temporary Bering Strait and from there migrated to Asia, while the others traveled to South America and evolved into today’s llama.

But, interestingly, the two groups of camelids still carry chromosomes that are similar enough to each other that camels can be bred with llamas and produce fertile offspring.

The average life expectancy of a camel is 40 to 50 years.

If you have a science subject you'd like Steven Law to explore in a future article, send him your idea at curious_things@hotmail.com.