Estimated read time: 10-11 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

BEAVERCREEK, Ohio — Imagine if cops could go back in time to watch a murder as it actually happened and track the movements of suspects and vehicles before and after the crime.

Surprisingly, the technology to do that — so-called wide-area persistent surveillance — has been around for years. But it hasn't been adopted by police departments, even in cities such as Salt Lake, where surveillance cameras are becoming a routine part of law enforcement.

The technology has been held back over concerns about costs and especially because of worries about big brother spying over a city.

The crime time machine

At the modest headquarters of Persistent Surveillance Systems LLC just outside Dayton, Ohio, founder Ross McNutt is frustrated because no police department so far has bought into his remarkable technology.

"I feel that we can reduce crime in a major city by 20 to 30 percent in a year," McNutt said. "You ask if I get frustrated that we're not in some of these cities? Absolutely."

The crime-watch system devised by McNutt is something like a crime time machine. Twelve cameras are mounted in a small, fixed-wing aircraft; the camera array is far too heavy for a typical civilian drone.

The plane circles over a city for many hours on end, continuously capturing the routine movements of vehicles and pedestrians, waiting for a crime to occur.

Each of the computer-coordinated cameras shoots 1 frame per second. The resulting photos are fused by computer into a single large-scale image — essentially a continuous aerial video — of a 32-square-mile urban landscape.

The resulting imagery is beamed back to the ground, captured by a portable antenna and fed into computers.

The video would typically be centered continuously on a high-crime area with the expectation that it will eventually record a major crime somewhere within the 32-square-mile observation zone. The image area would cover roughly one-third of Salt Lake City.

After years of sporadic testing in the U.S. and Mexico, those eyes in the sky have recorded many terrible things.

I feel that we can reduce crime in a major city by 20 to 30 percent in a year. You ask if I get frustrated that we're not in some of these cities? Absolutely.

–Persistent Surveillance Systems LLC founder Ross McNutt

"So far to date, we've seen 39 murders as they've occurred," McNutt said.

As the ongoing surveillance video streams into Persistent Surveillance Systems computers, company analysts can react when a report of a major crime comes in. Minutes or hours after it actually occurred, they can "rewind" the recorded video and zoom in to a specific address and watch the crime as it unfolded.

Watching murders in Mexico

"In this case, we see a person get out of this car and shoot dead two people in this car and get back in this car and drive off, and we're able to see where that person goes," McNutt said as his computer screen replayed a murder recorded by the company's cameras circling over Juarez, Mexico.

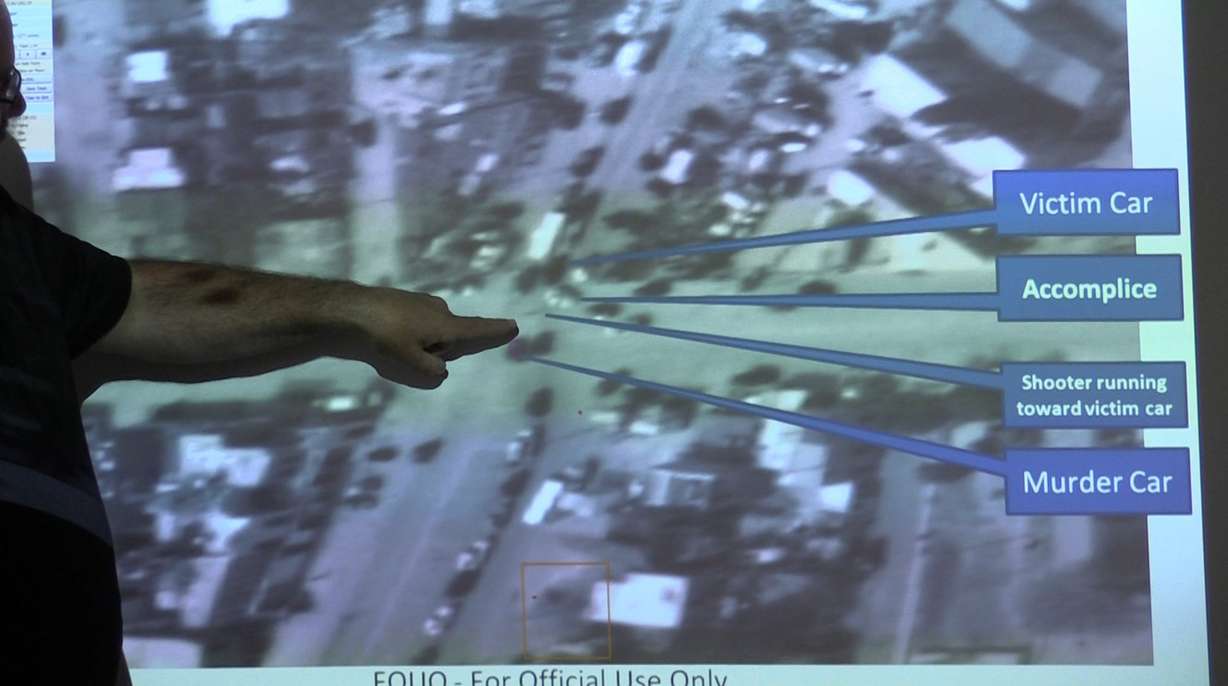

In PowerPoint presentations and computer demonstrations, McNutt likes to narrate another murder in Juarez that was captured by Persistent Surveillance Systems cameras in 2009.

"These three cars here just held their last premurder meeting," McNutt said, pointing to fuzzy images of three cars that converged at a Juarez intersection as part of a murder plot.

Then he pointed to a scene that took place moments later at an alley a few blocks away.

"This group is going to kill a person right here," he said. "You've got three vehicles and a shooter on foot right there."

The image quality of the zoomed-in recording is relatively poor; an individual person is unrecognizable, appearing as a single pixel on the screen. Cars are much easier to watch as they move from place to place but are too indistinct to be individually identified.

Seconds after someone reported the murder to police, McNutt's analysts hit rewind and zoomed in on the alley.

Related:

"And we were able to go back in time and watch exactly what happened," he said as he pointed at the screen and narrated the murder. "So right here is your shooter. Right there is your victim. Right there appears to be the shot."

As tiny images moved up the alley immediately after the murder, McNutt continued the narrative.

"Now, this time, we're going to follow the actual shooter. He's going to get into that second car, and now the second car is going to drive off," he said.

The recorded shot shows everything that happened in a 32-square-mile area. That means Persistent Surveillance Systems analysts can zoom in on multiple locations and follow different simultaneous actions that might be of interest.

For instance, by zooming in on actions in the alley just seconds after the murder, analysts were able to conclude that several bystanders were probably drug criminals as well.

"They actually run out toward the body and then run down the alleyway after the shooter," McNutt said. "That tells us they're likely armed and have some responsibility for protection (of the victim)."

Meanwhile, the cars were speeding away.

"You see both of them run the red lights," McNutt said as he zoomed into an area a few blocks away from the alley. "They're driving here about 75 mph."

The power of the surveillance technology is clearly demonstrated by what happened next: By going forward in time on the recorded video, analysts followed the suspects' vehicles to their destination several miles away.

"The car stops," McNutt said. "The person gets out of the passenger side, the same side the shooter got into, and they walk right into this second house there. Now what we're going to do is go into our Google Earth."

By zooming into the same address on Google Earth shortly after the murder, the analysts can capture an image of the building and transmit it to pursuing police.

"We can actually take a screenshot of this and send it to an officer's cellphone with the address," McNutt said, "so … when they go knock on the door, they get the right door. And in this case, it gave them more than enough information to actually solve the crime."

The Persistent Surveillance Systems technology broke the Juarez case wide open.

"Because we've got this whole area recorded, we actually followed these people for about 4 ½ hours total — 45 minutes prior to the murder, 3 ½ hours after the murder," McNutt said.

"Not only did we identify eight locations this kill squad was operating at, we also identified two cartel headquarters, their operating locations, a major drug delivery and a lot of other information," he said.

It all started in Iraq

McNutt settled in Ohio after a career in the U.S. Air Force. He originally developed the technology more than a decade ago to help the military track down roadside bombers that were killing and injuring scores of U.S. soldiers in Iraq.

In what was called Operation Angelfire, a plane circled over Fallujah with cameras. When a hidden bomb exploded, analysts could hit "rewind" to watch the person planting the bomb. Then they could track him back in time to see where the bomb was made.

"It was very effective," McNutt said.

It was so successful, in fact, that the military also used the surveillance technology in Afghanistan, he said.

McNutt said he continues to do surveillance in foreign countries under contracts with the military. But no American city has bought into his technology, partly because it's expensive, he said.

Persistent Surveillance Systems offers cities its service for $1.5 millon to $2 million per year. That includes 150 hours per month of surveillance, as well as professional video analysis and electronic coordination with police.

It's a lot of money for a system that's only useful in certain types of crime situations.

"I think any city could probably use it," said Salt Lake Police Sgt. Mark Buhman, who oversees the department's intelligence center. "The question is how often it would be beneficial to them and whether it's worth the financial impact that it would cost to the city."

Salt Lake City has had surveillance cameras on towers in the Pioneer Park area for years. This year, portable camera towers were brought into play, parked by police in high-crime neighborhoods.

"We often see a reduction in those areas," Buhman said, "so they're a good crime deterrent."

But with Salt Lake City's relatively low murder rate, wide-area surveillance might be a financial stretch.

McNutt argues, though, that crime creates huge costs for victims, government and business.

"What we believe is that even a 10 percent reduction of crime in Salt Lake would be about $32 million a year back to the community in value," he said.

Buhman said he believes those theoretical savings would not likely result in smaller police departments or lower law enforcement budgets. So wide-area surveillance may not be realistic tool in Salt Lake.

"In the costs that I've seen, it's a little prohibitive for probably our circumstances," he said.

Is big brother watching?

McNutt's system has been tested in several American cities, including Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Compton, California. But as he tries to sell the service, he faces a much bigger obstacle than cost: Many people are nervous about high-flying eyes in the sky watching what people are doing.

Even in McNutt's backyard — Dayton, Ohio — police backed away from it.

"Activists rose up and protested it, and the community was deeply uncomfortable with it," said Jay Stanley, senior policy analyst for the American Civil Liberties Union. "There was (also) a huge outcry in Baltimore when it was revealed that this technology had been deployed."

Stanley argues that persistent surveillance is a potential threat to the rights of citizens.

"That gives … the government the power to press the rewind button on any of our lives — where you've been, looking at your associations, who you've been with, looking at your politically and sexually and religiously and medically oriented activities," he said.

Randy Dryer, a professor at the University of Utah's S.J. Quinney College of Law, said he believes the state Legislature would outlaw wide-area surveillance if any local police departments tried to use it.

Two years ago, Utah lawmakers banned the use of drones for such purposes, and Dryer says they would quickly extend the ban to fixed-wing aircraft. He also believes the U.S. Supreme Court would declare it unconstitutional because it invades privacy rights and undermines protections against unreasonable search and seizure, Dryer said.

There's just something about an eye in the sky that makes Americans uncomfortable, he said.

"(There's) a general unease when people are always watching you," Dryer said, "particularly when that someone is government who has the power to take away your liberties."

McNutt argues that his cameras are set to cover such a wide area that, for now at least, the image quality when zoomed in is too low to actually identify anyone.

"People are a single pixel," he said, "so you can't tell who they are, what color they are, whether they're gay or straight — nor do we ever care."

McNutt is working with community groups in Baltimore, hoping they will push city leaders into adopting his surveillance technology. He says people in high-crime cities, who live in constant fear of violence, would overwhelmingly support his effort.

Persistent Surveillance Systems' promotional video includes a statement by an unidentified Baltimore resident endorsing the aerial surveillance.

(There's) a general unease when people are always watching you, particularly when that someone is government who has the power to take away your liberties.

–Professor at the University of Utah's S.J. Quinney College of Law Randy Dryer

"We have a major problem in this city," she said. "We have a lot of shootings and a lot of murders, and that shouldn't be happening. And so to find something that can help that situation and to show that someone out there cares anough and wants to better this community, that's what it's all about."

McNutt sums up the debate in a few words: "There is a fundamental trade-off between security and privacy."

It's a trade-off that becomes all the tougher to sort out as surveillance technology gets better and better.