Estimated read time: 12-13 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

PARK CITY — A fragment of cloth, faded by five years of exposure to sun and snow, proved the critical clue in ending a missing hiker mystery in the High Uintas Wilderness last week.

The bundled tent, partially buried beneath a boulder above a remote mountain lake, caught the eye of Kelvin Judd. He, his brother Kimball and father Mark were trying to find a way up to the saddle between Allsop Lake and Dead Horse Lake on Aug. 18 when they spotted the unlikely item amid a boulder field.

“I got my binoculars out and started looking around and there were other things that turned out to be his belongings kind of scattered from the ledge to his backpack. His backpack was the lowest article we found,” Judd said.

The other items included trekking poles and a hiking boot. All of the detritus sat out in the open, minuscule amid a sea of loose rock, invisible except for from above.

The boot, they soon realized, contained bone fragments.

“It was kind of meant to be. I don’t think it was a coincidence,” Judd said. “If we’d have been 10 or 20 feet more or less a different direction and hadn’t happened to look down, we’d have probably walked right past some of the stuff.”

Judd lives in Pleasant View but grew up in Coalville and has spent much of his life in the Uinta Mountains. He was on a family outing to the scenic lake, which sits at the headwaters of the East Fork Bear River, when he made the unlikely discovery.

The afternoon sun was starting to dip low on the horizon as the father and sons picked their way across the uneven ground, looking for clues as to the deceased hiker’s identity. Inside his heavy pack they found a sealed, bear-resistant can containing enough food to last several days.

“We saw the Australian flag sticker on his canister of food,” Judd said.

They also saw an ID card bearing the name Eric Robinson.

The search for Eric Robinson

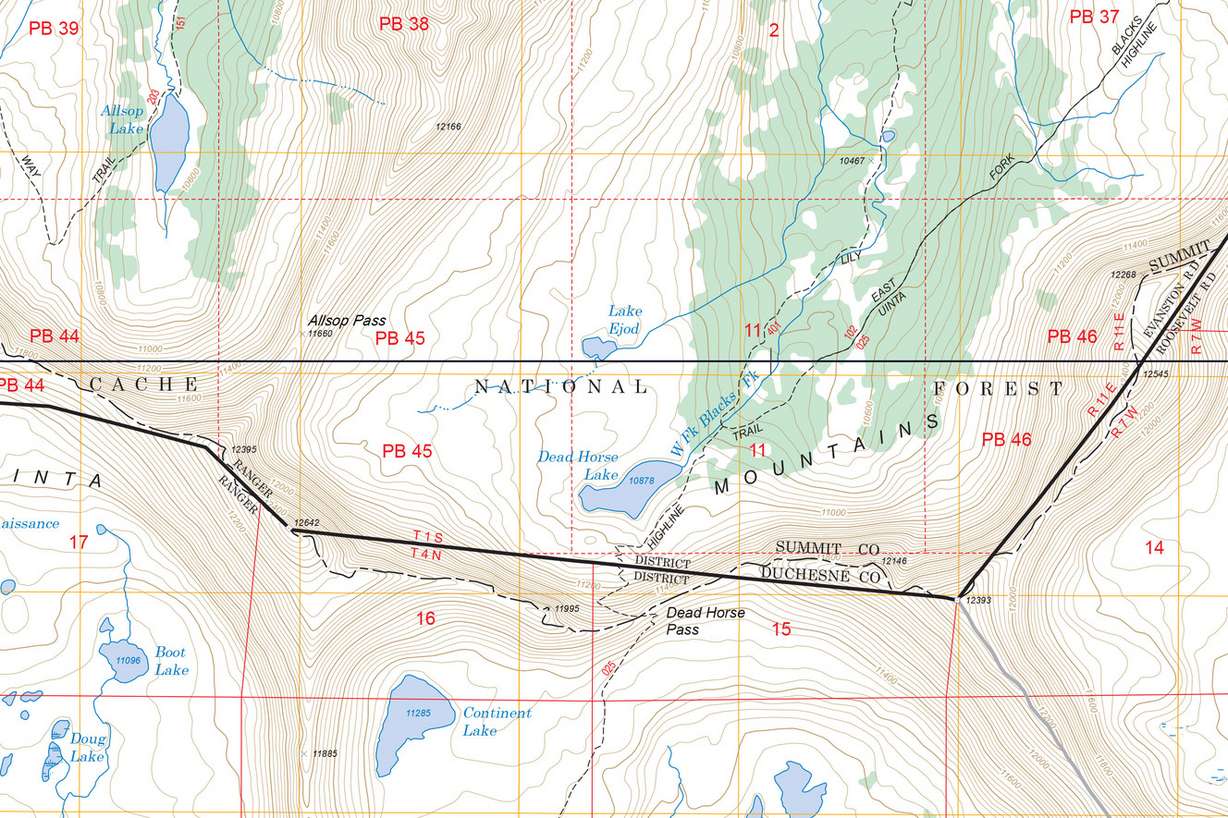

Robinson, 64, had set out alone on July 28, 2011, from the Chepeta Lake Trailhead northwest of Vernal with the intent of covering more than 60 miles of the Uinta Highline Trail. The strenuous trail runs east to west, generally following the crest of the range along its southern edge. Its western terminus sits on the Mirror Lake Highway at the Highline Trailhead northeast of Kamas.

An intensive search for Robinson launched on Aug. 8, 2011, a day after he failed to arrive in the Mirror Lake area as planned. The effort focused around the Yellowstone Basin in Duchesne County, because a group of Boy Scouts had reported speaking with Robinson there on Aug. 2.

The Scouts told investigators he seemed to have made a navigational error, as he was a few miles to the south of the Highline Trail when they encountered him. Professional searchers and volunteers poured over the area, generating news coverage in both Utah and in Australia.

Robinson, an engineer by trade, was fastidious about his planning and packing.

“He was a minimalist person but not a minimalist on safety,” Robinson’s wife, Marilyn Koolstra, said.

She came to Utah during the search effort and visited the high mountain basins, seeing the barren alpine tundra for herself. A helicopter carried her up above the tree line, where patches of snow were still present.

“There had been severe storms up in the mountains around the beginning of August and that was something that had crossed our minds, a lot of water or perhaps a lightning strike,” Koolstra said.

The family also worried Robinson might have been attacked by a bear.

“We had some piece of mind in that Eric carried and EPIRB (emergency position indicating radio beacon) and he would have set that off if he were able.”

There were no tell-tale bleeps from the radio beacon. As the search dragged on, the Duchense County Sheriff’s Office warned Robinson’s wife, son, four step-children and 11 grandchildren they might never find him.

“When we returned from the search, in my mind I wrote my own last chapter of what could have happened,” Koolstra said. “That was the way I gave closure to something that could hang without any resolution.”

No way to call for help

Revelation was slow to dawn on Kelvin Judd. He had not heard of Robinson, or of the weeks-long effort to find him five years prior.

“We usually follow those types of stories in that area because that’s where we like to hunt and fish and camp,” Judd said.

High above them, the Judds could hear another group of hikers coming over the top of the saddle, unofficially referred to as Allsop Pass.

“The human element of it kind of touched us. We thought ‘well, someone’s lost their life here’,” Judd said. “We spent an hour and a half just kind of looking for different things there and by that time it was terribly late in the afternoon so we just turned around and headed back down to our camp.”

The Judds knew they needed to report the find, but had no means of doing so. Cellphone service is nonexistent in the area, leaving satellite phones and beacons as the only reliable means of communication.

Unfortunately, Robinson had to spend one more night alone on the mountain.

Trying to positively identify the remains

Dan Ransom arose the morning of Friday, Aug. 19 expecting to spend the day the same way he had the one prior.

He and his party were in the middle of an ambitious hike that in some ways mirrored the Highline Trail. Only, while the Highline stays mostly to the south of the Uinta crest on a maintained path, Ransom’s path involved off-trail route finding along the north slope.

Morning light filtered through the pines when Mark Judd walked into Ransom’s camp. The backpackers were sipping their morning coffee and preparing for a long, physically strenuous day. In a low voice, Judd explained what he and his sons had found the previous afternoon.

“He mentioned that they’d recovered an ID,” Ransom said. “My first thought was ‘is it the gentleman from Australia?’”

Judd confirmed the name on the card matched the one in Ransom’s mind: Eric Robinson.

“I’d remembered a lot of details from the original search and rescue,” Ransom said.

The two groups gathered to share information. Ransom told the Judds about Robinson’s story. He also offered to use his personal locator beacon to send word to the authorities.

Once that was done, Ransom and his party faced a decision. Should they continue on with their hike, or remain in the Allsop Lake area to offer assistance? They opted to stick around while search and rescuers ferried into the basin by helicopter.

“It was very somber obviously,” Ransom said. “We were just kind of waiting.”

The Duchesne County Sheriff’s Office had led the original search for Robinson, because the location where he’d last been reported fell within Duchesne County’s boundaries; however, the pack and remains had come to rest a few hundred yards over an invisible line within Summit County.

Kelvin and Kimball Judd led the searchers up to the boulder field.

“They did a thorough search of the area and were able to collect a number of bone fragments. Some intact, some were as small as an inch or two in length,” Summit County Sheriff’s Detective Sgt. Ron Bridge said.

Investigators needed to be sure, however. They sent those bone fragments to the Utah Office of the Medical Examiner for DNA analysis. Results are still pending.

Even in the absence of forensic review, circumstances seemed clear. It appeared Robinson had fallen to his death from the cliff bands below Allsop Pass.

“It’s a 52 percent grade combined with about a 40- to 50-foot cliff and another 60- to 70-foot cliff. That is the path that we believe he took, straight off of that and ended up down at the bottom,” Bridge said.

Even DNA testing though cannot definitively prove that theory.

“It would be impossible for us to figure out exactly why he ended up where he was,” Bridge said.

Part of the challenge comes from the scattered, fragmentary nature of the remains.

“Over five years, things can move through snow, they can move through avalanches, they can move through the natural terrain and the rocks breaking off of the cliffs and rolling down the hill,” Bridge said.

What happened to Robinson?

Marilyn Koolstra awoke to the sound of her phone ringing at about 5:20 a.m. on Saturday morning.

“When you get woken by the phone, it’s something of a shock,” Koolstra said. The voice on the other end of the line sounded familiar, though she hadn’t heard it in years. It was Duchesne County Sheriff David Boren.

He informed her of the discovery, explaining where and how her husband’s remains had been discovered.

“The location and the information that I have has brought a lot of peace of mind to the family and myself,” Koolstra said.

Others though are left to puzzle over why it took five years to solve the mystery.

“I think a lot of people are going to say ‘how could no one have found it?’ Or maybe people will want to blame search and rescue,” Dan Ransom said. He dismissed the idea that more could have been done to find Robinson. “There’s a reason it took five years.”

For one, the massive scale of the search area. Search and rescue operations in the Uintas are often hampered by geography, unpredictable weather and a relatively short summer season.

“His backpack had a massive amount of food in it. He had a personal locator beacon. He had a bear canister. He had a GPS device,” Ransom said. “But it does seem that he was obviously struggling with navigation.”

As evidence, Ransom points to Robinson’s run-in with the Boy Scout group in Yellowstone Basin.

“Maybe that Scout troop got him back on the right path,” Ransom said.

If so, Robinson would have continued west over Porcupine Pass into the Oweep Creek basin before then crossing Red Knob Pass into the West Fork Blacks Fork drainage.

There, he would have faced a daunting climb.

“You really don’t have a tricky-looking pass until Dead Horse,” Ransom said.

The Highline Trail carves an exposed and unlikely route up and over the Uinta headwall at Dead Horse Pass. Snow fields can cover the trail well into summer, especially following heavy winters. The winter of 2010-2011 was just such a season.

In that case, a hiker might mistake Allsop Pass as the proper route. The navigational situation could also have been complicated by the fact the Uintas run east to west, while many other mountain ranges tend north to south.

However, it’s possible Robinson could have decided Dead Horse Pass was simply too unsafe given the existing conditions. In that case, he might have left the Highline Trail intentionally.

Relatively few people hike to the top of Allsop Pass, but faint paths do ascend to it from the eastern side. Cairns, stacks of rocks meant to indicate routes, dot the top of the pass.

Those paths do not appear on any trail maps. The U.S. Forest Service does not have a developed trail to the pass and insists the route is not used by the domestic sheep that graze in the West Fork Blacks Fork drainage.

“I have heard of a few adventurous folks that have crossed this pass, but it has never been recommended by the Forest Service as a route to be tried because of its steepness,” Uinta-Wasatch-Cache National Forest Wilderness, Trails and Special Uses Manager Bernard Asay said. “There is no regulation requiring visitors to stay on the system trails, and there are a few who will travel cross-country.”

Whatever the reason, Robinson was one of those few.

“He’s not an idiot. This is not a guy that was just incompetent,” Ransom said. “This is a guy that probably knew fairly well what he was doing; he just didn’t understand maybe some of the nuances that make the Uintas unique.”

The paths abruptly stop at the pass, at the top of those tall cliffs on the Allsop side. Hikers hoping to descend to Allsop Lake must take one of two risky routes down from the saddle. One descends a steep couloir, or gully, while the other requires traversing north above the cliffs on loose ground to a large scree slope.

Robinson did not appear to have attempted either route. His scattered gear came to rest somewhere between the two, suggesting an unexpected fall or an attempt to descend the cliff faces directly.

One thing all parties involved in the discovery seemed to agree upon was the idea Robinson’s fate was not a result of negligence.

“He had recently recreated in the Himalayan Mountains. He was very experienced at hiking in the backcountry and it just seems that a terrible accident took his life,” Detective Sgt. Bridge said.

“When you’re a solo hiker, there’s an element of risk,” Ransom said. “You’re making that decision.”

Robinson's wife grateful for everyone's help

In the week since the discovery, Koolstra had a chance to speak with the Judd family.

“That’s such a respectful, caring family who had the same kinds of passions and appreciation of the wilderness and remote places,” Koolstra said.

She also shared similar sentiments for the sheriff’s deputies who kept hope alive for five long years.

“I can only express my gratitude to them for everything that they have done. The way that they have conducted themselves and the way they have responded and kept me informed, I’d just like to say thank you.”